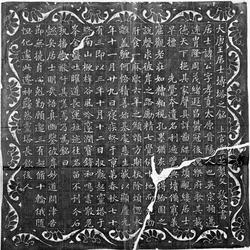

Although the "Warrior of the Holy King" introduced here is not as influential and well-known as the "Lingfei Sutra", it is similar to the latter in at least two points: first, it has long been identified as the work of Tang Zhong Shaojing; Second, it was also engraved in a series of texts (for example, Bao Shufang's "An Suxuan Dharma Notes" of Shexian County in the Qing Dynasty included this sutra), and it was once widely circulated.

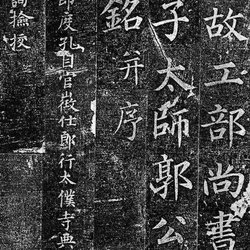

Zhong Shaojing, whose courtesy name is Keda, is said to be a descendant of Zhong Yao. He lived in the early Tang Dynasty and was over eighty when he died. People at that time called him "Xiao Zhong". There are biographies in both the new and old "Tang Shu". Song Zenggong's "Yuanfeng Lei Manuscript" said: "Shaojing's calligraphy and painting are beautiful, vigorous and methodical, but sincere and incomparable." Mi Fu's "History of Calligraphy" calls Shaojing's calligraphy "round and vigorous". However, except for the inscription on the back of the stele of the Prince Shengxian, it is almost difficult for future generations to recognize its true face in Mount Lu. As a result, some good people or profiteers claimed that some of the more outstanding Jingsheng calligraphy was the work of Zhong Shaojing.

According to Mr. Qi Gong's research, the "Ling Fei Jing" was attached to Zhong's name after Yuan Yuan Jue. I don’t know when the Sutra of the Wheel-turning Holy King was also named Zhong Shaojing, but it is certain that this is also the speculation of later generations and cannot be relied upon.

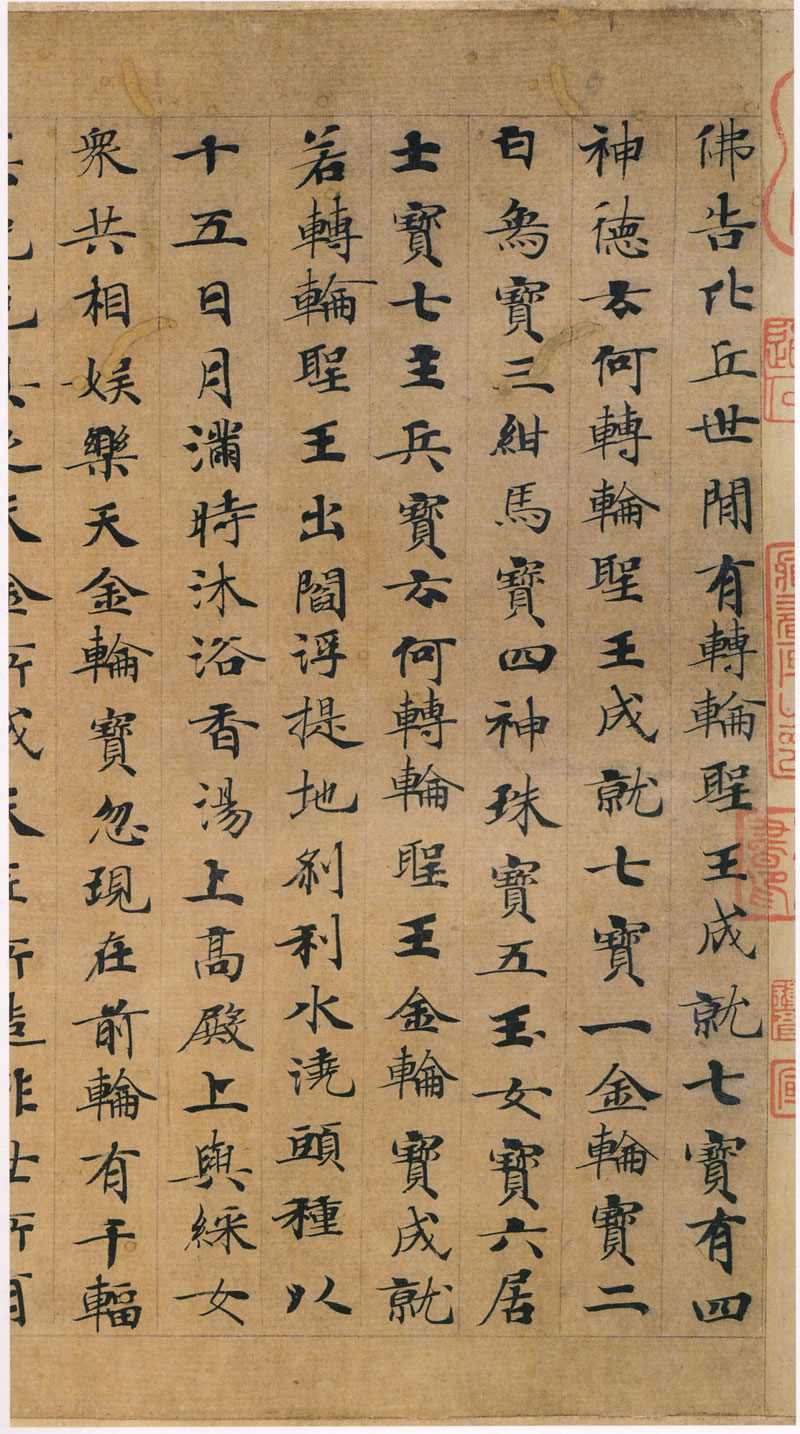

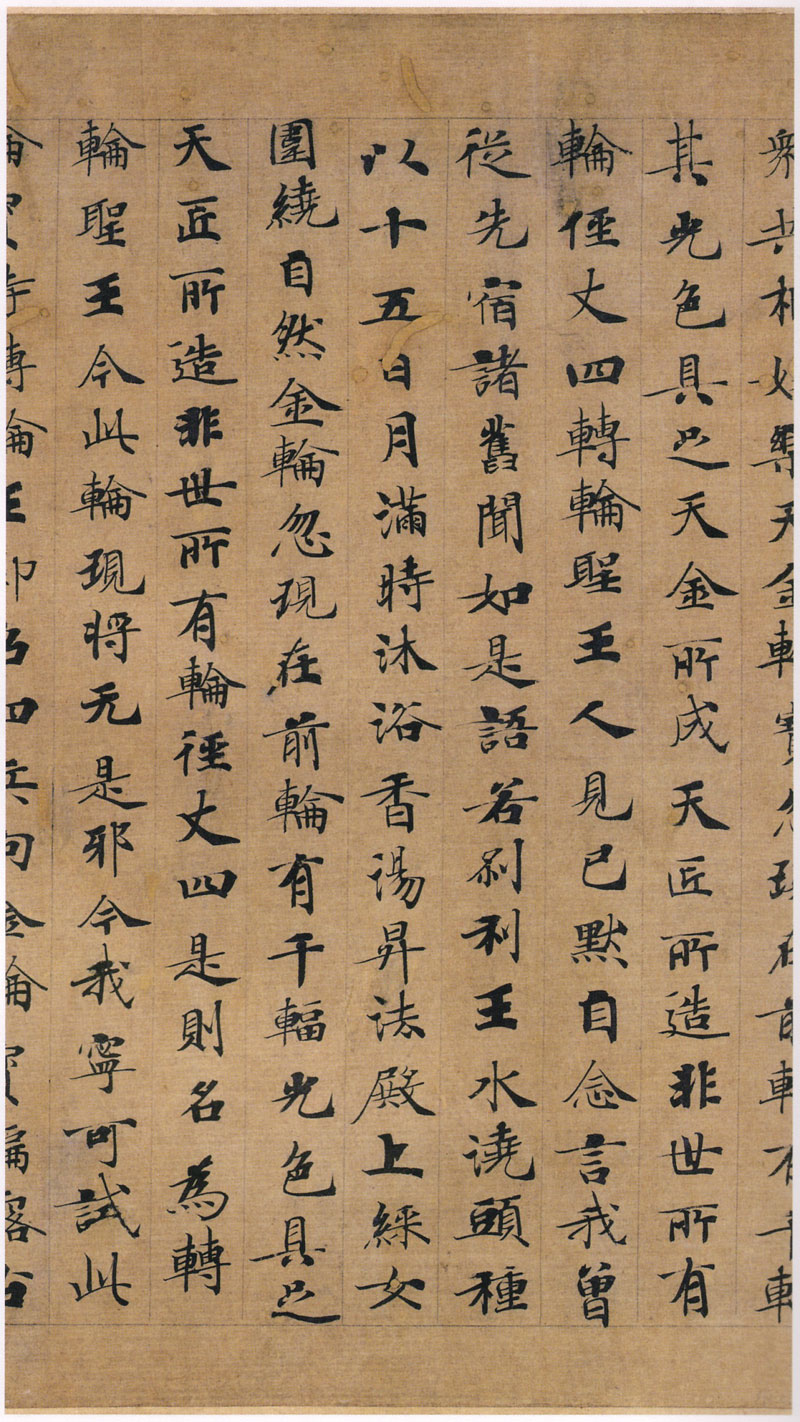

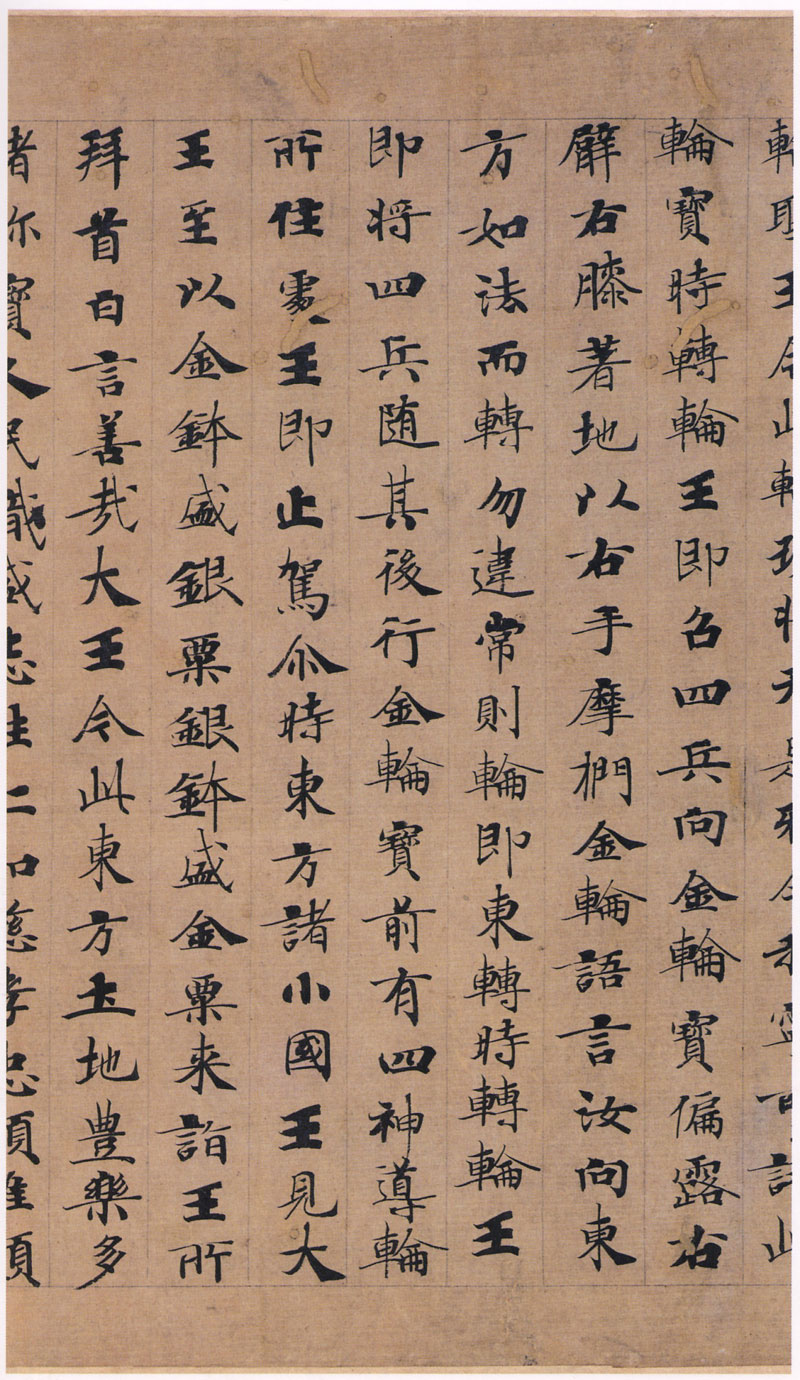

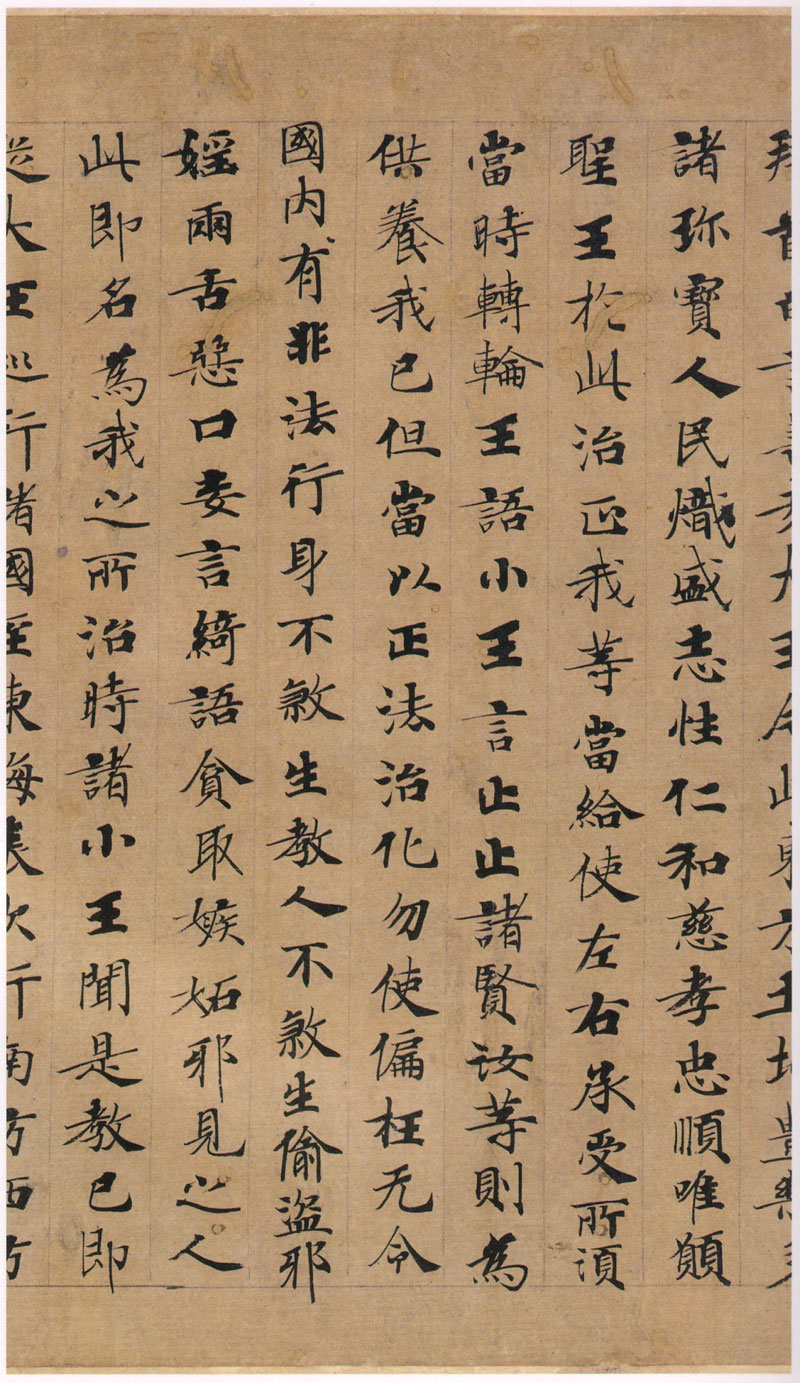

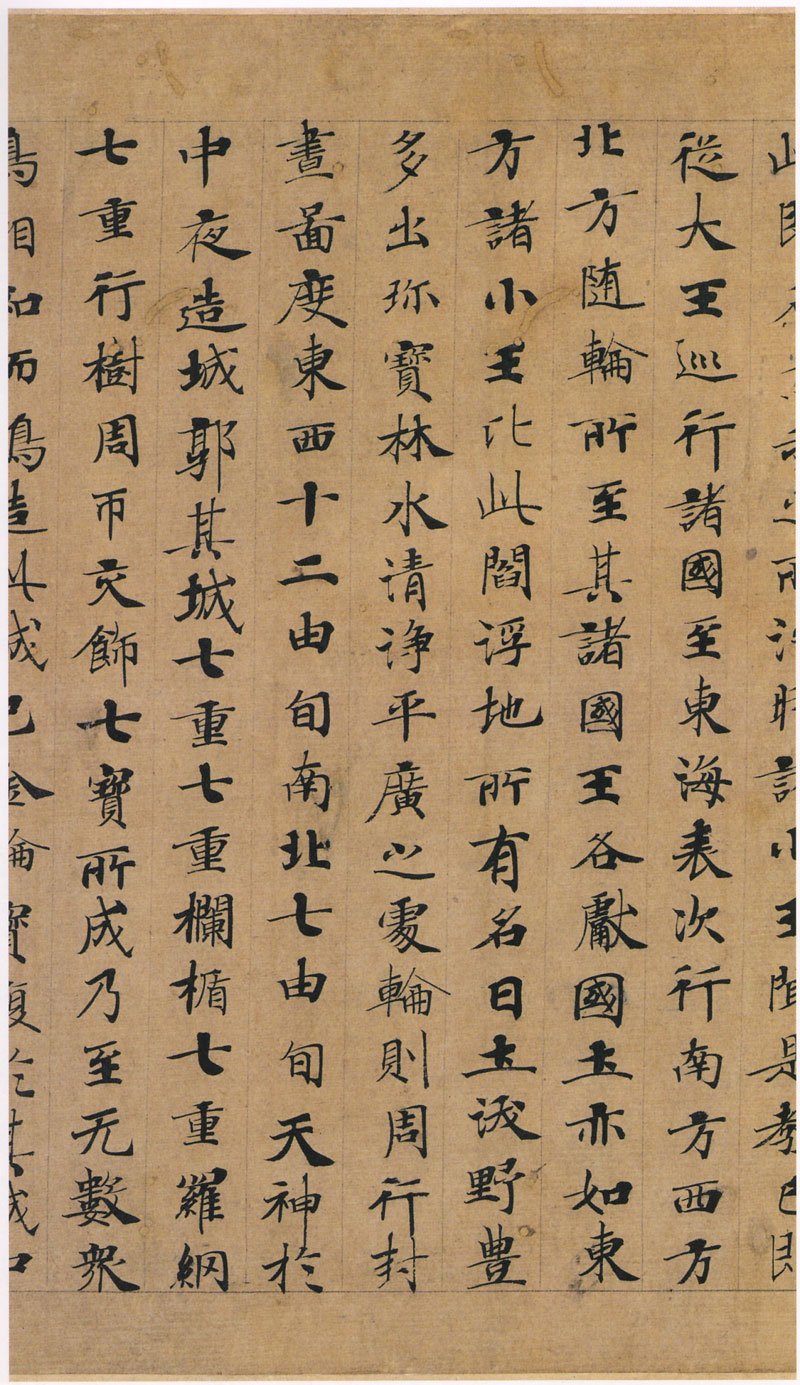

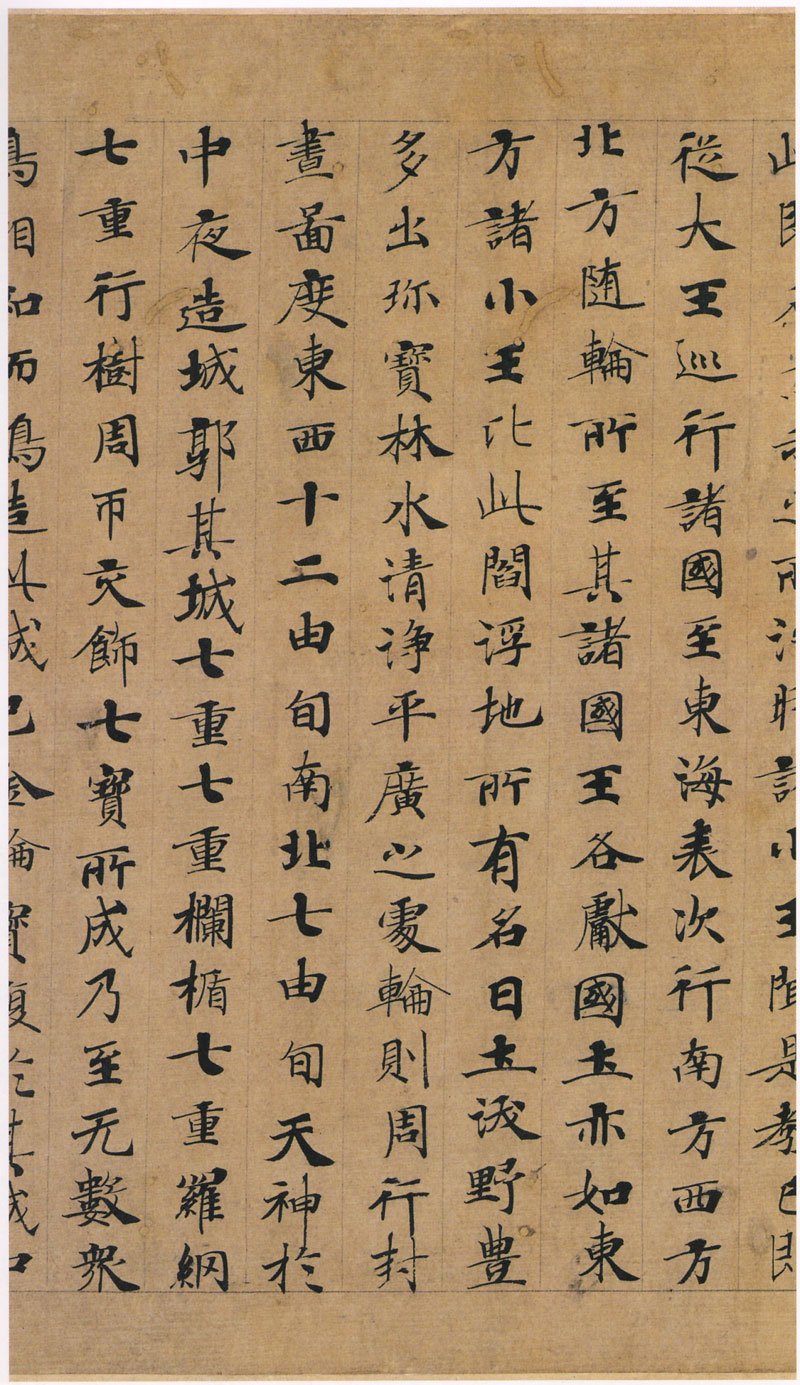

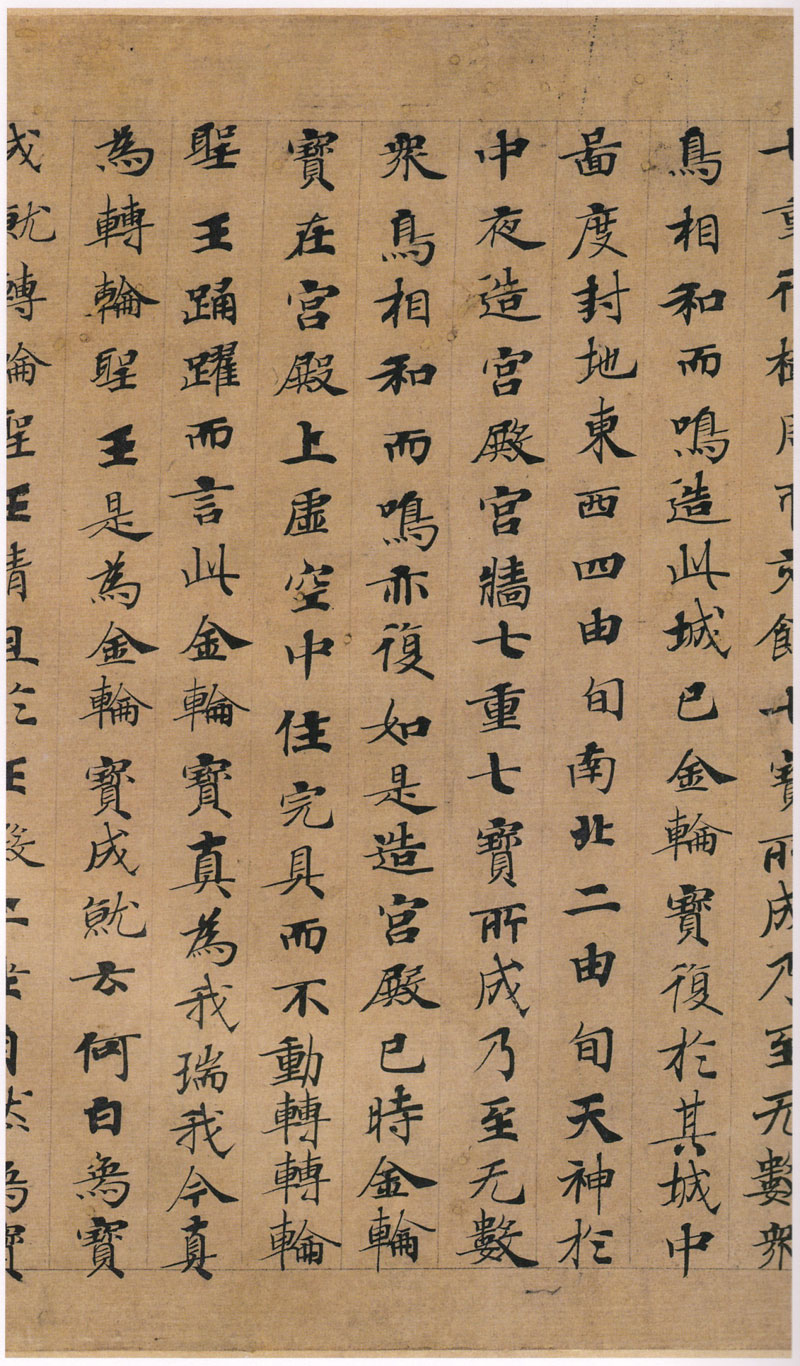

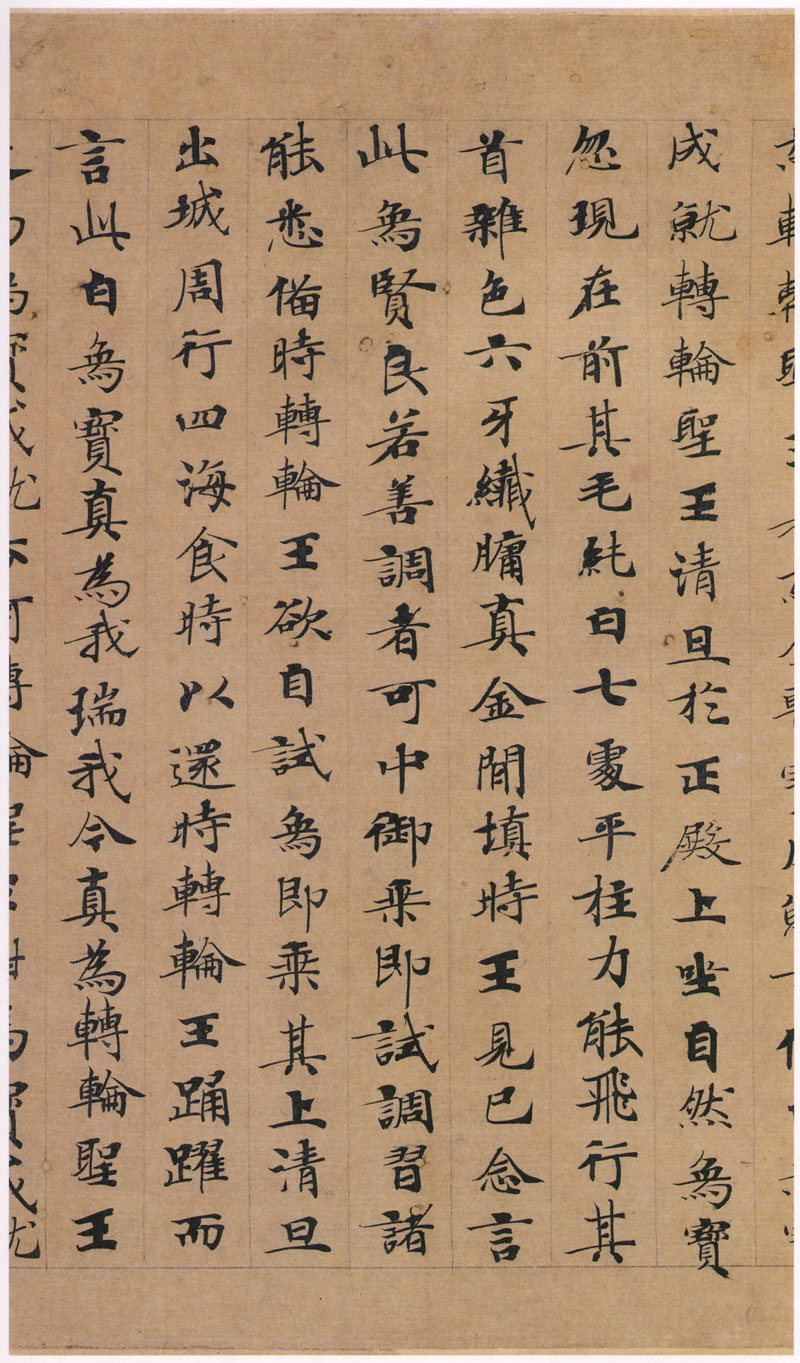

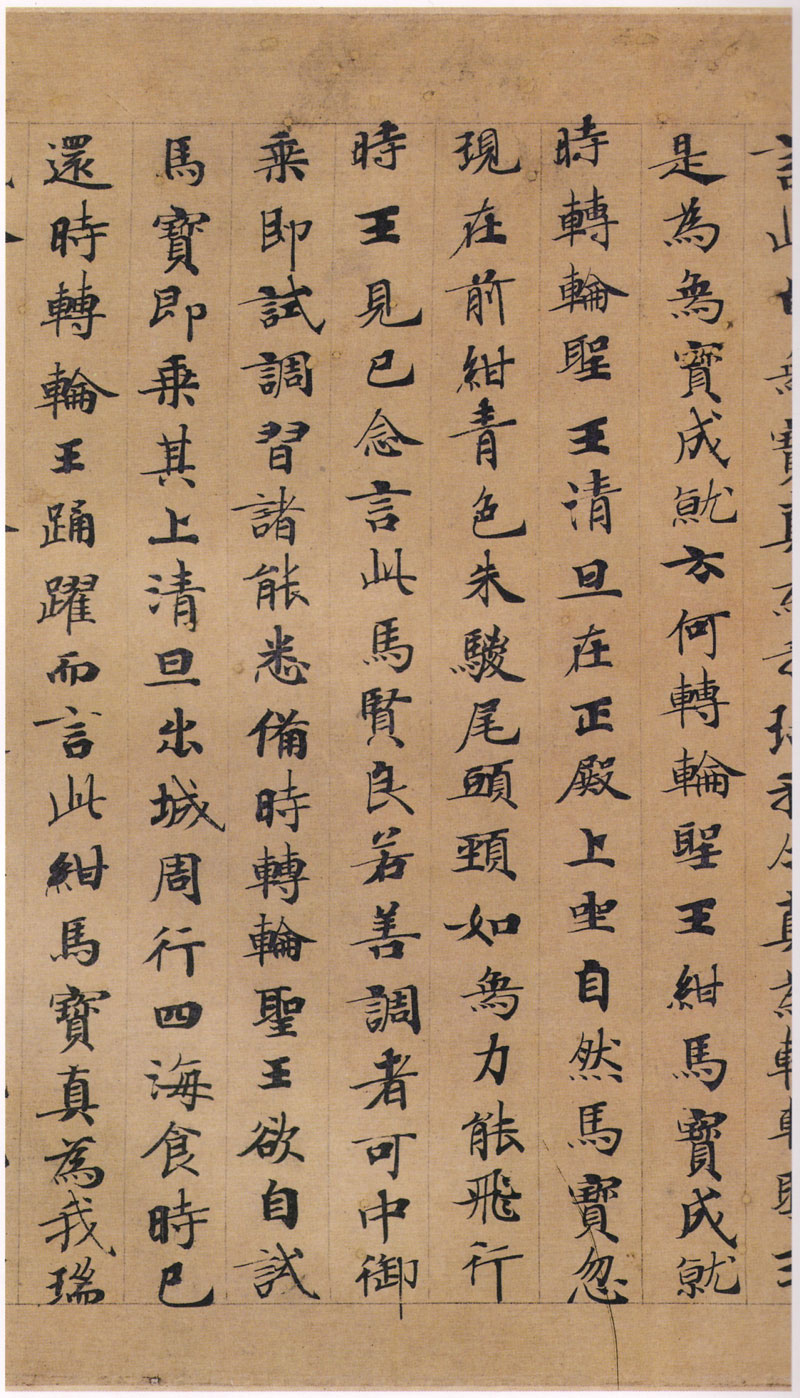

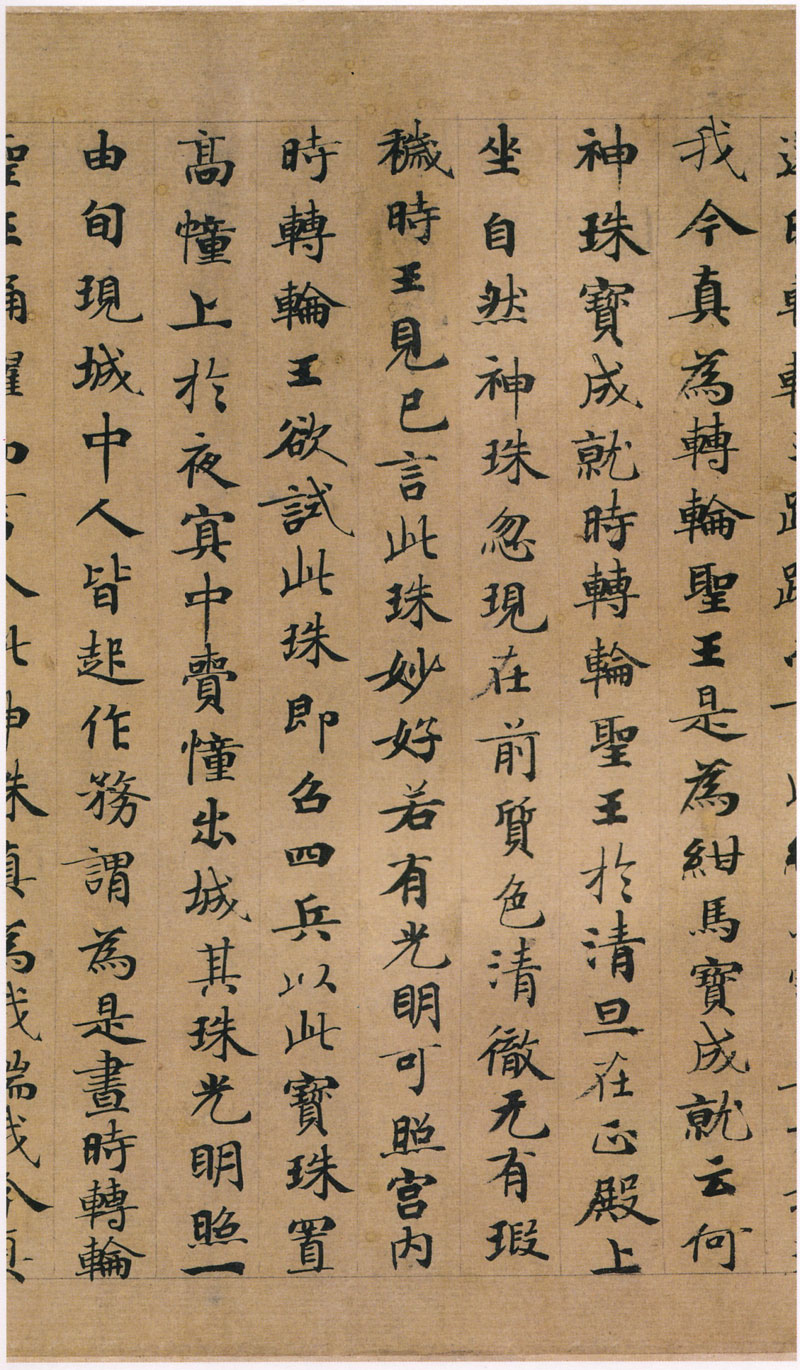

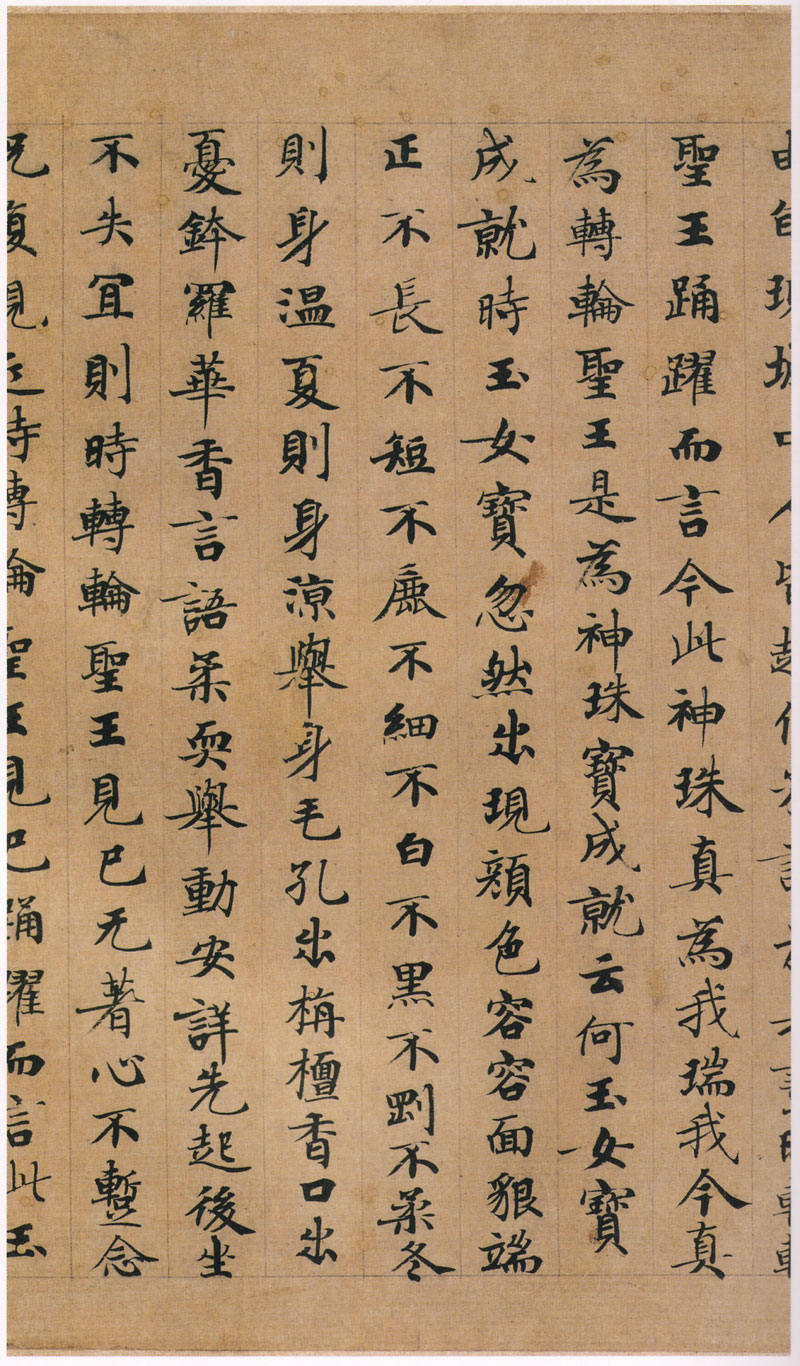

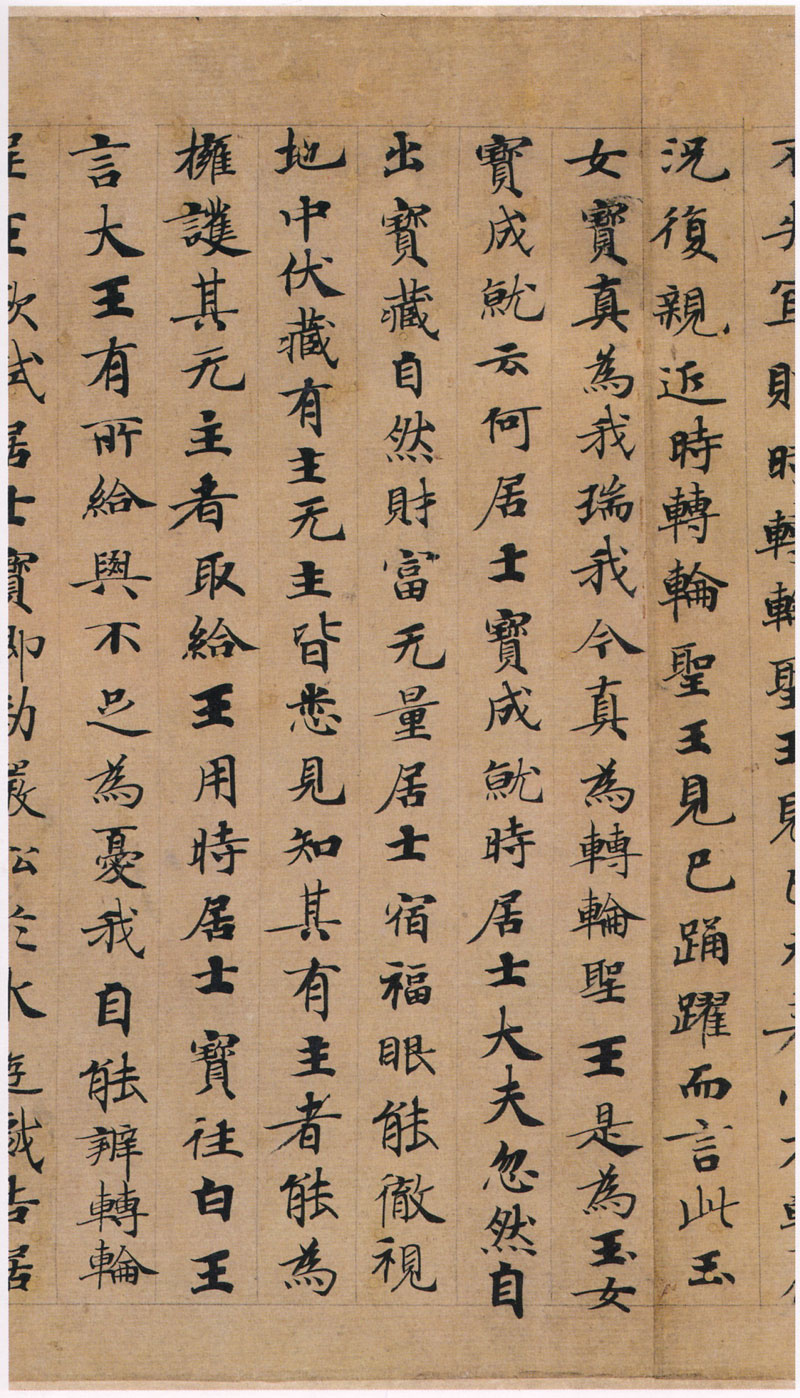

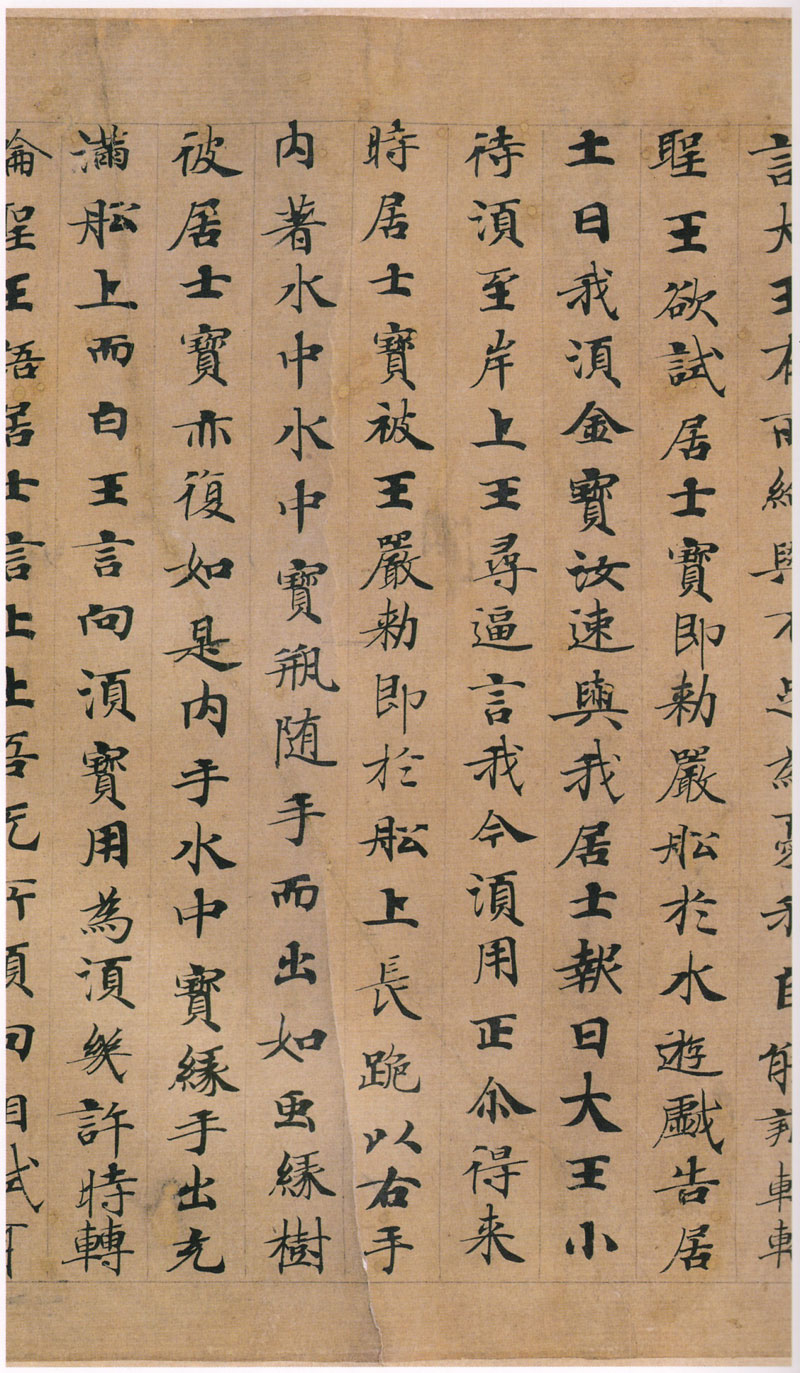

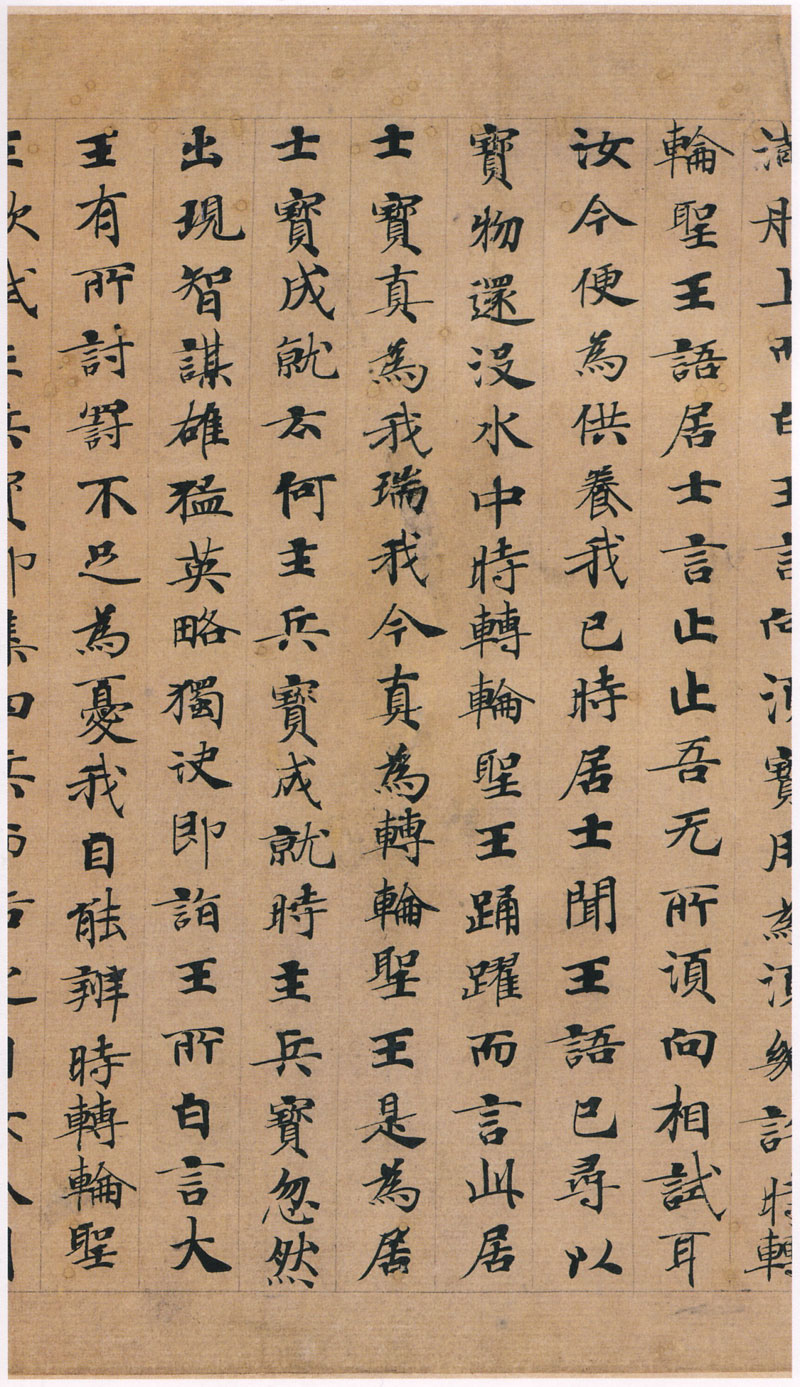

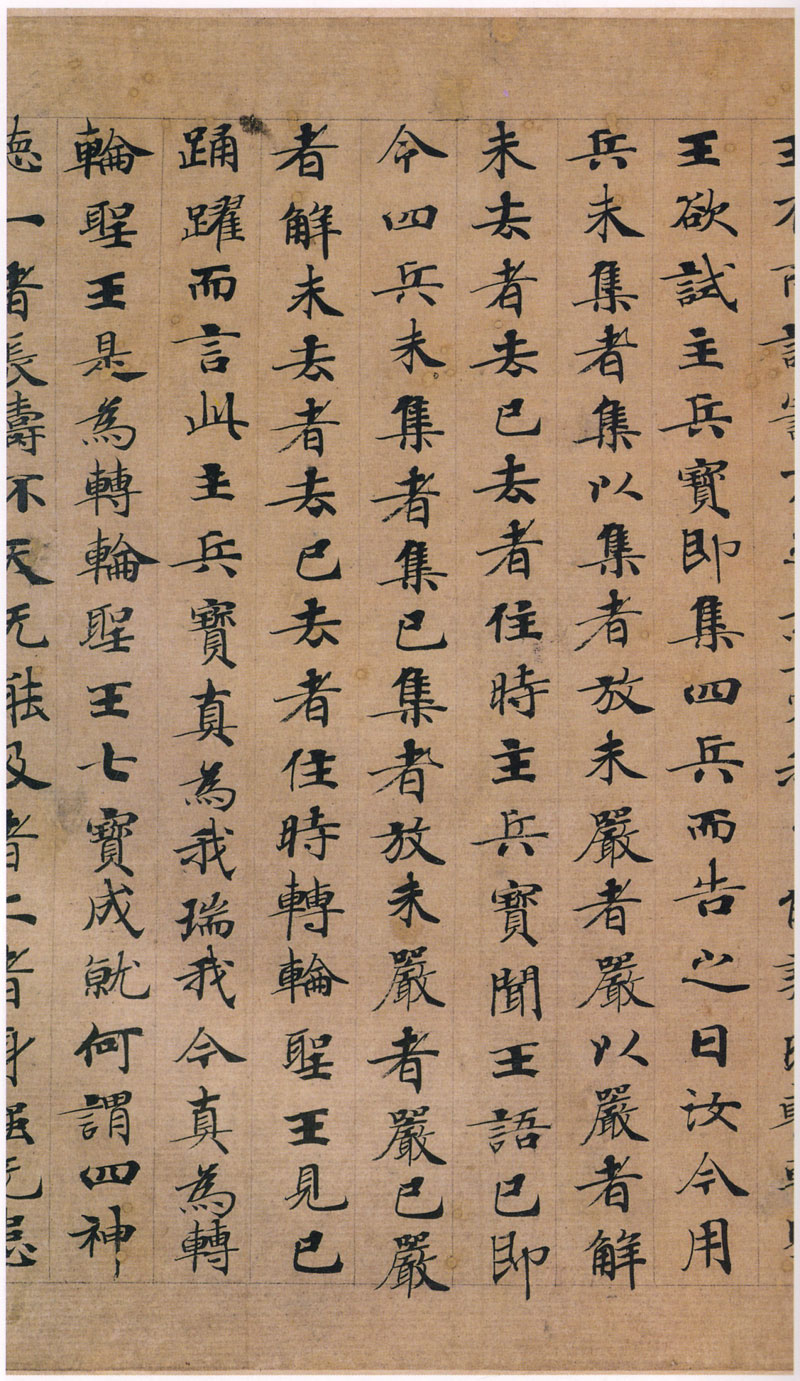

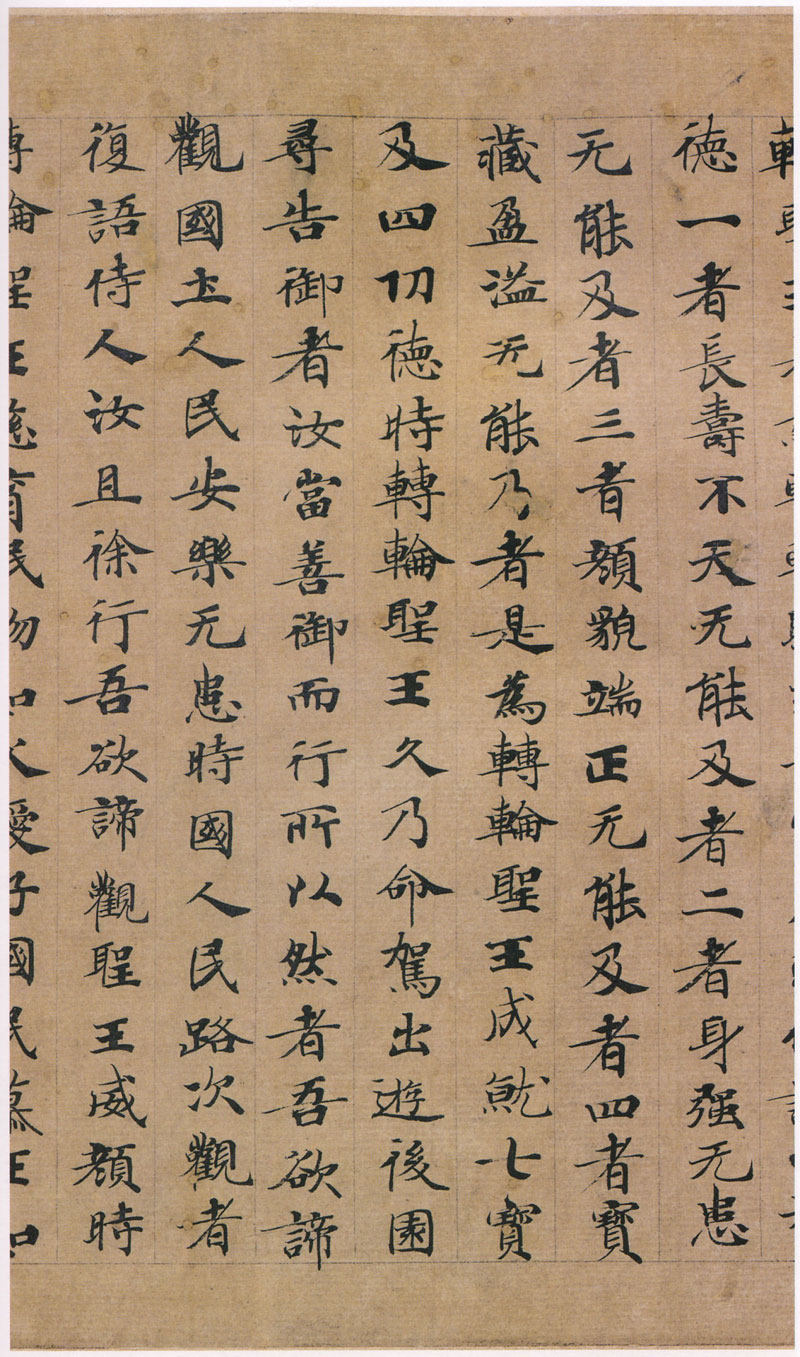

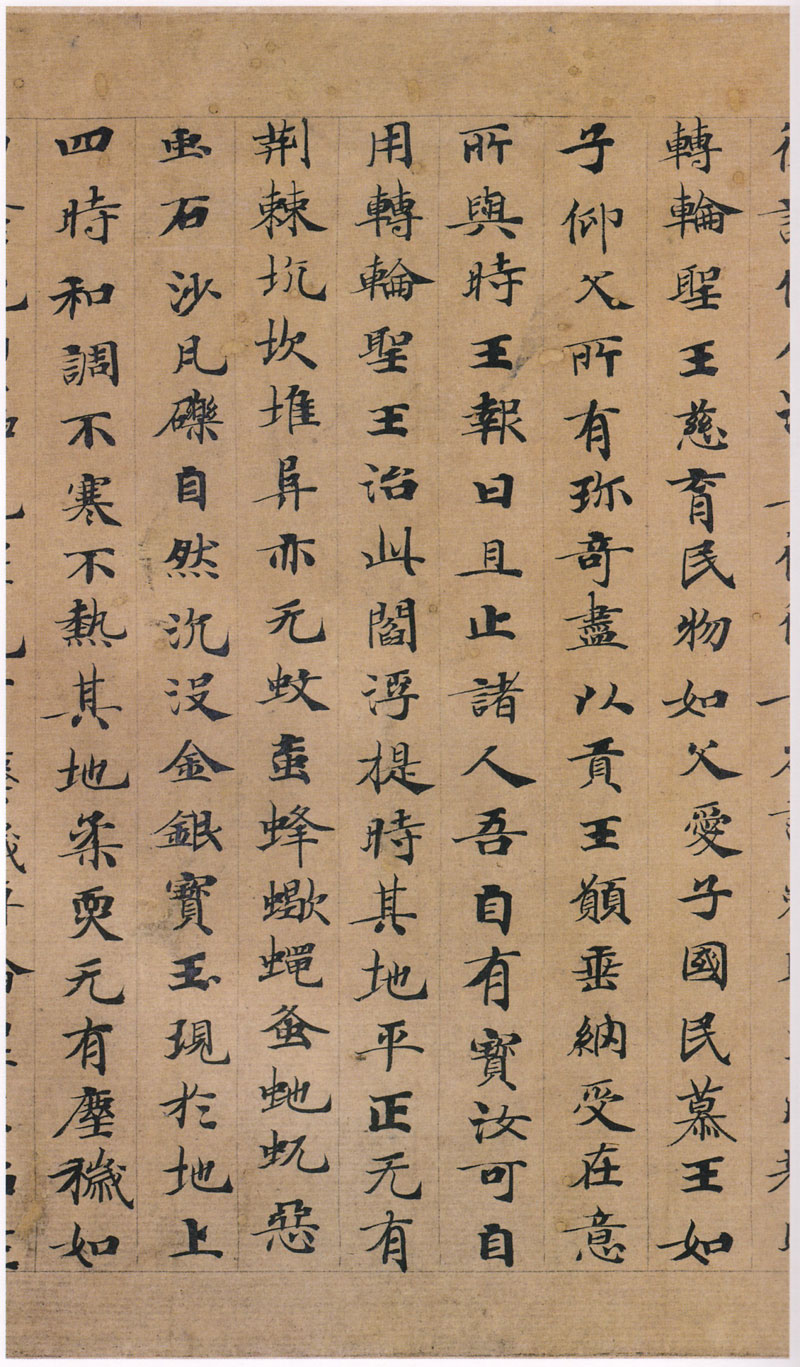

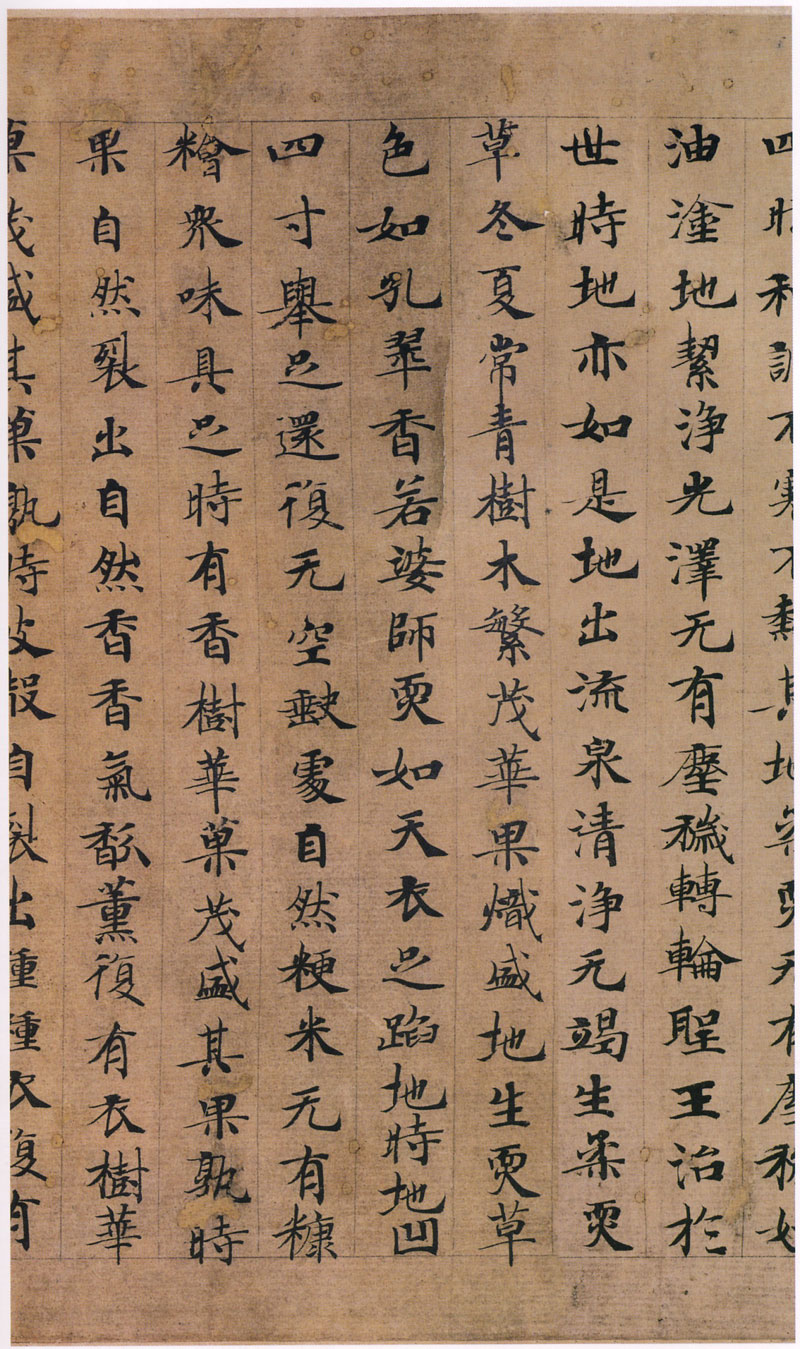

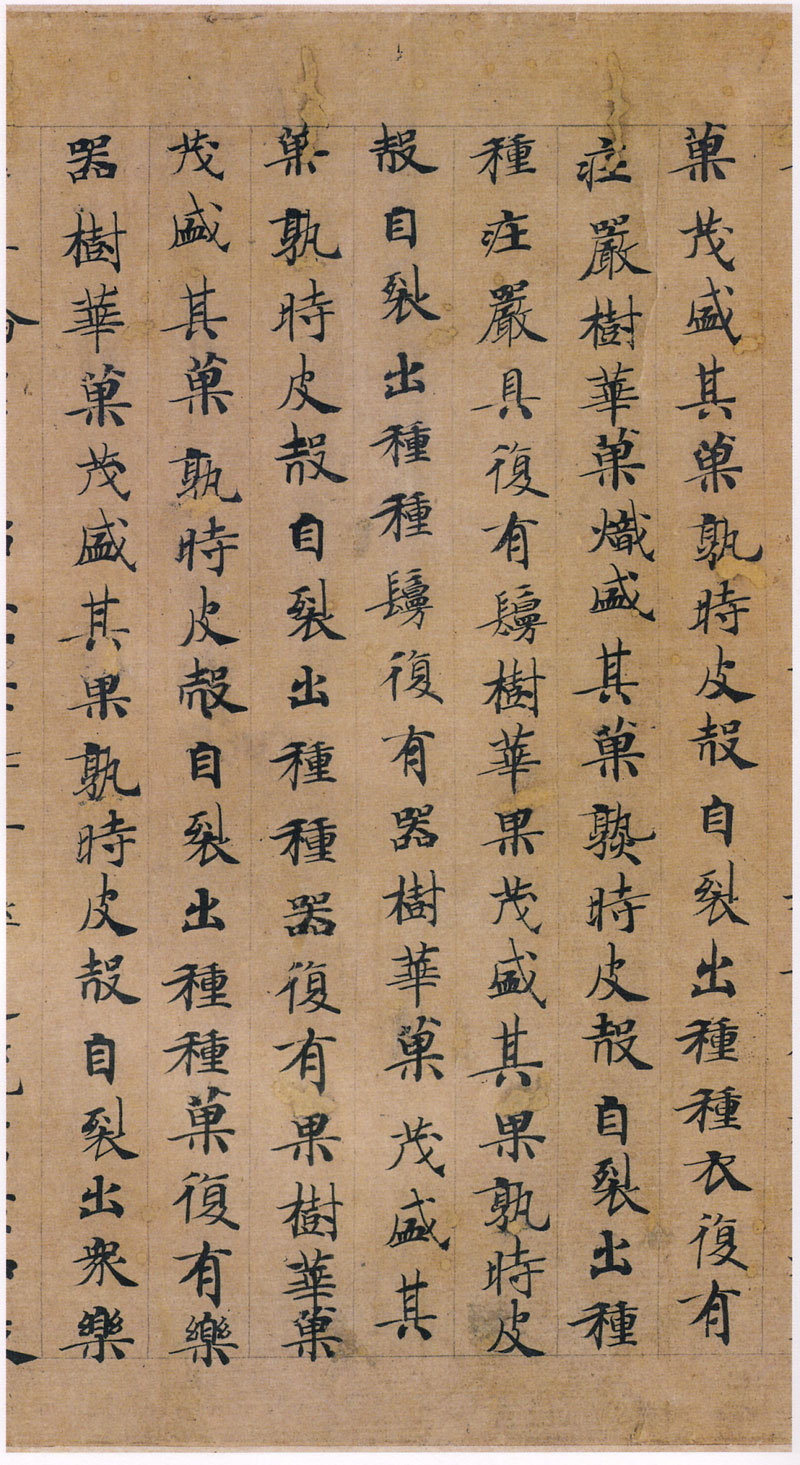

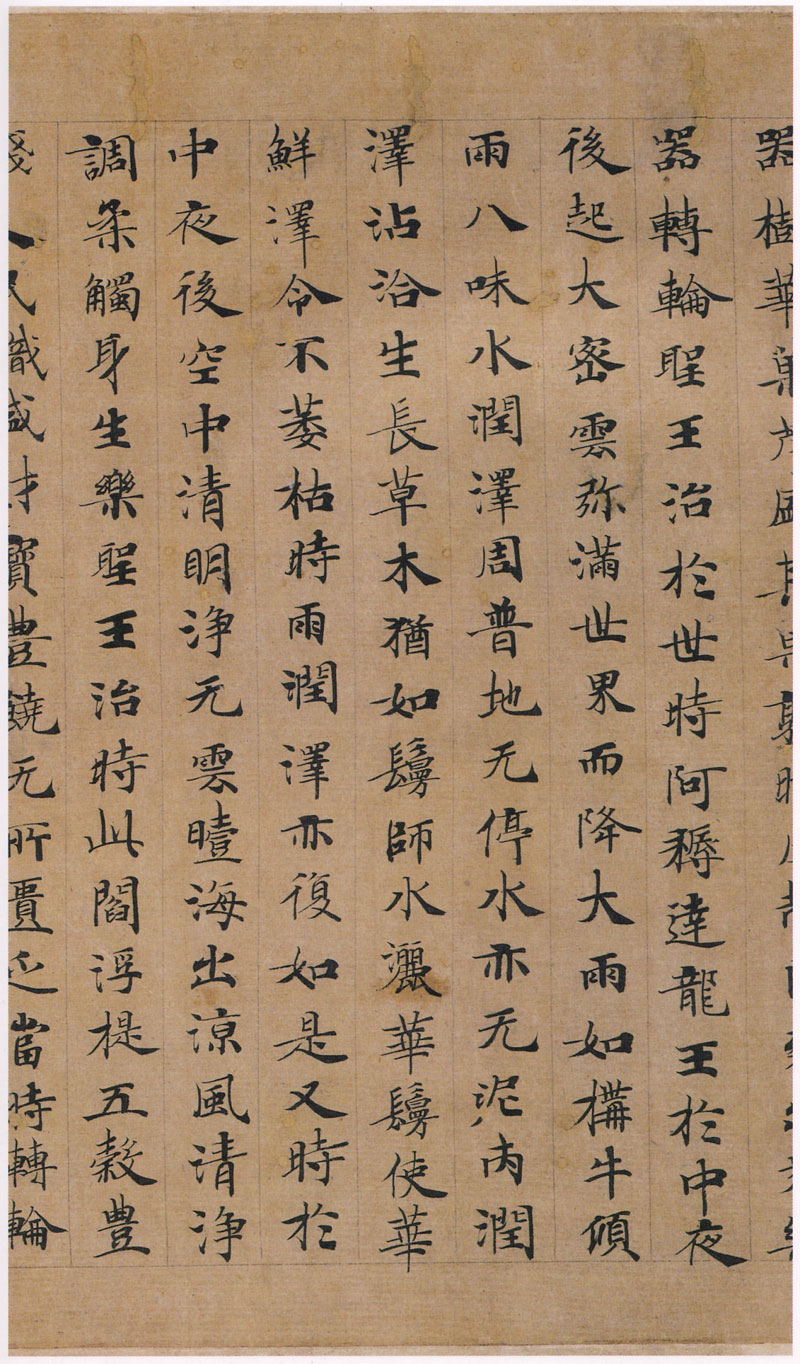

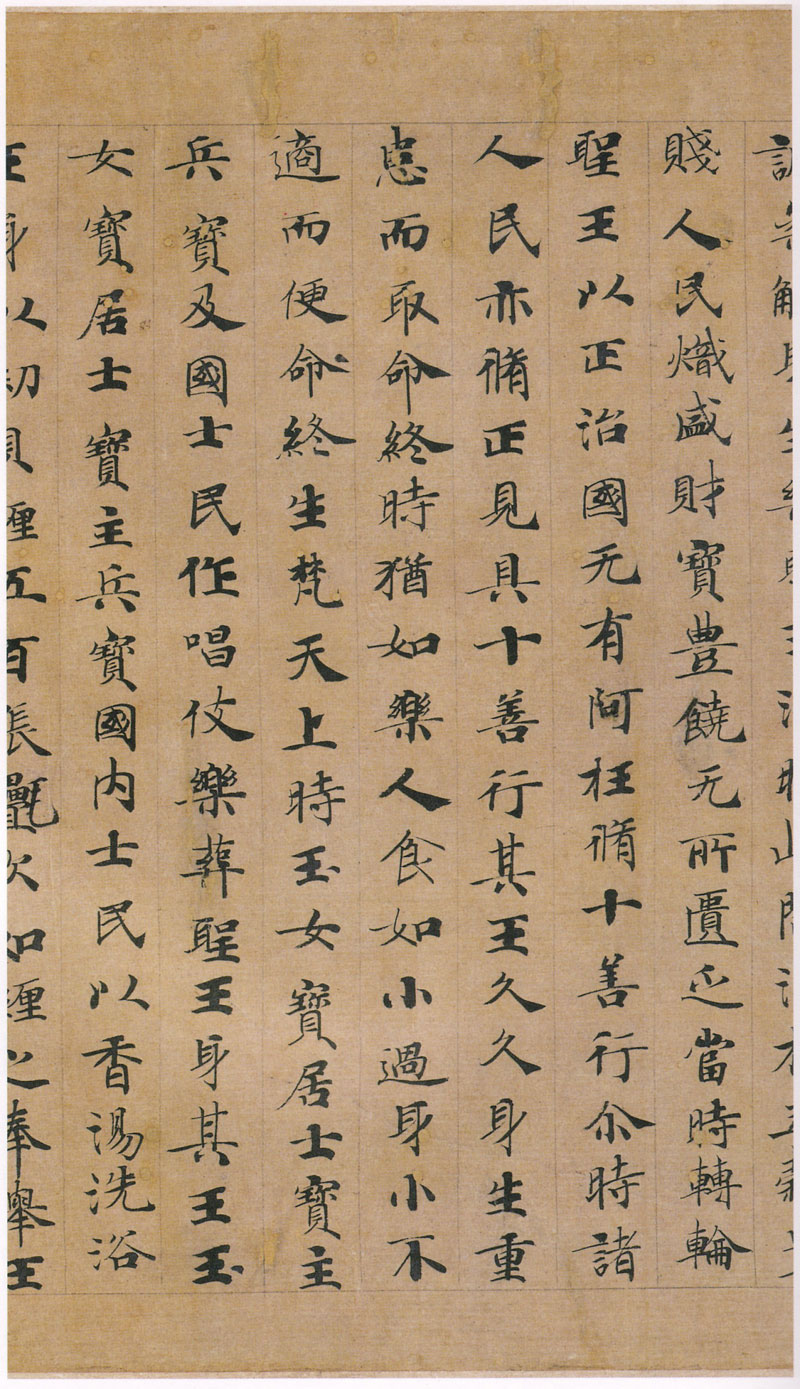

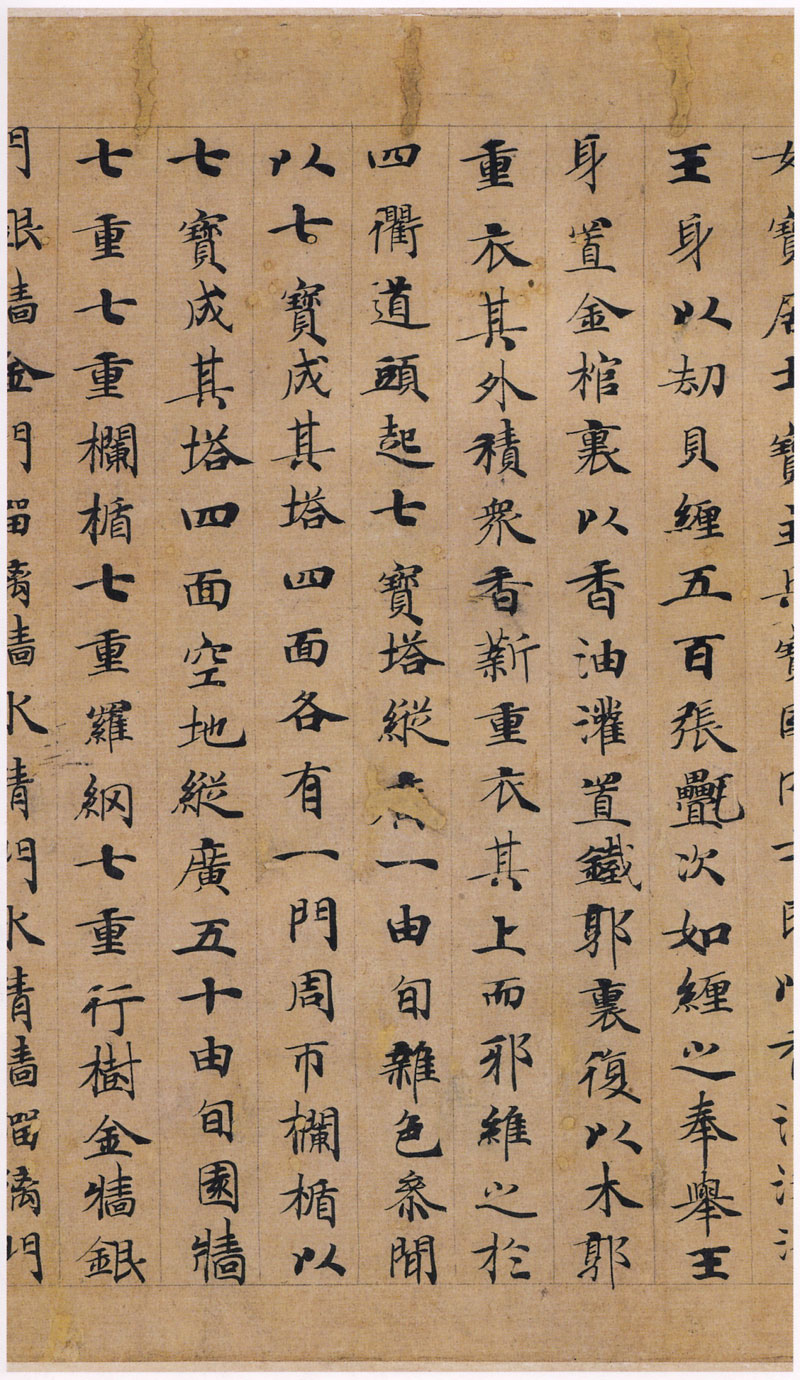

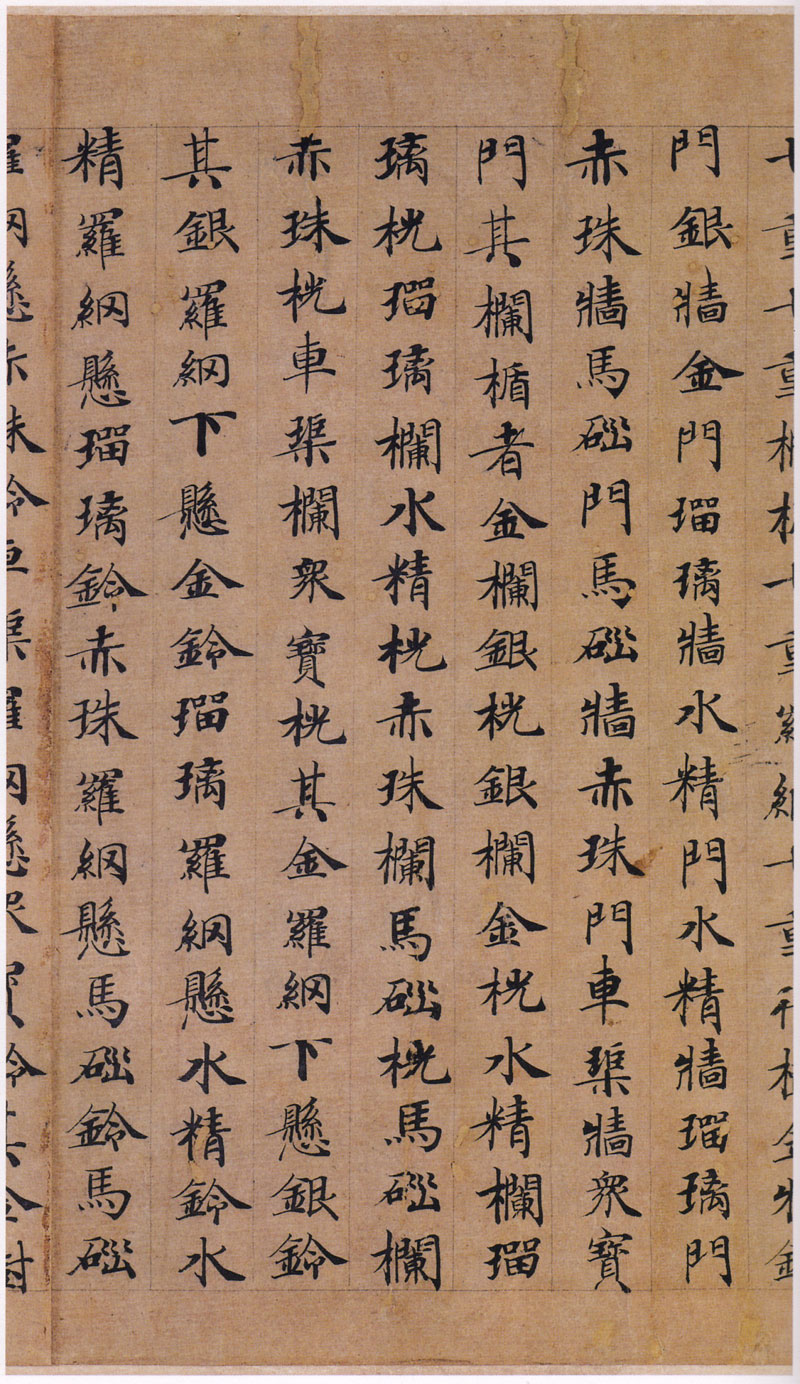

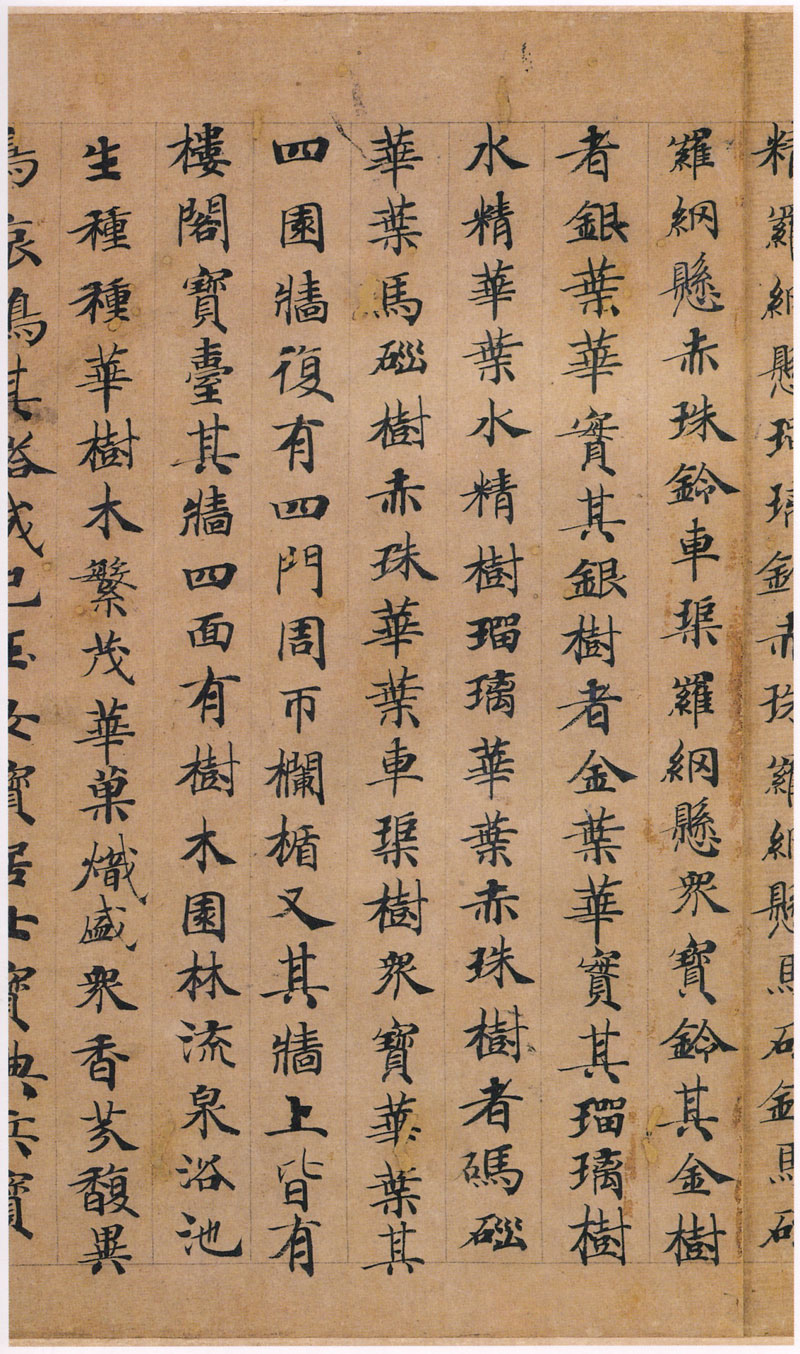

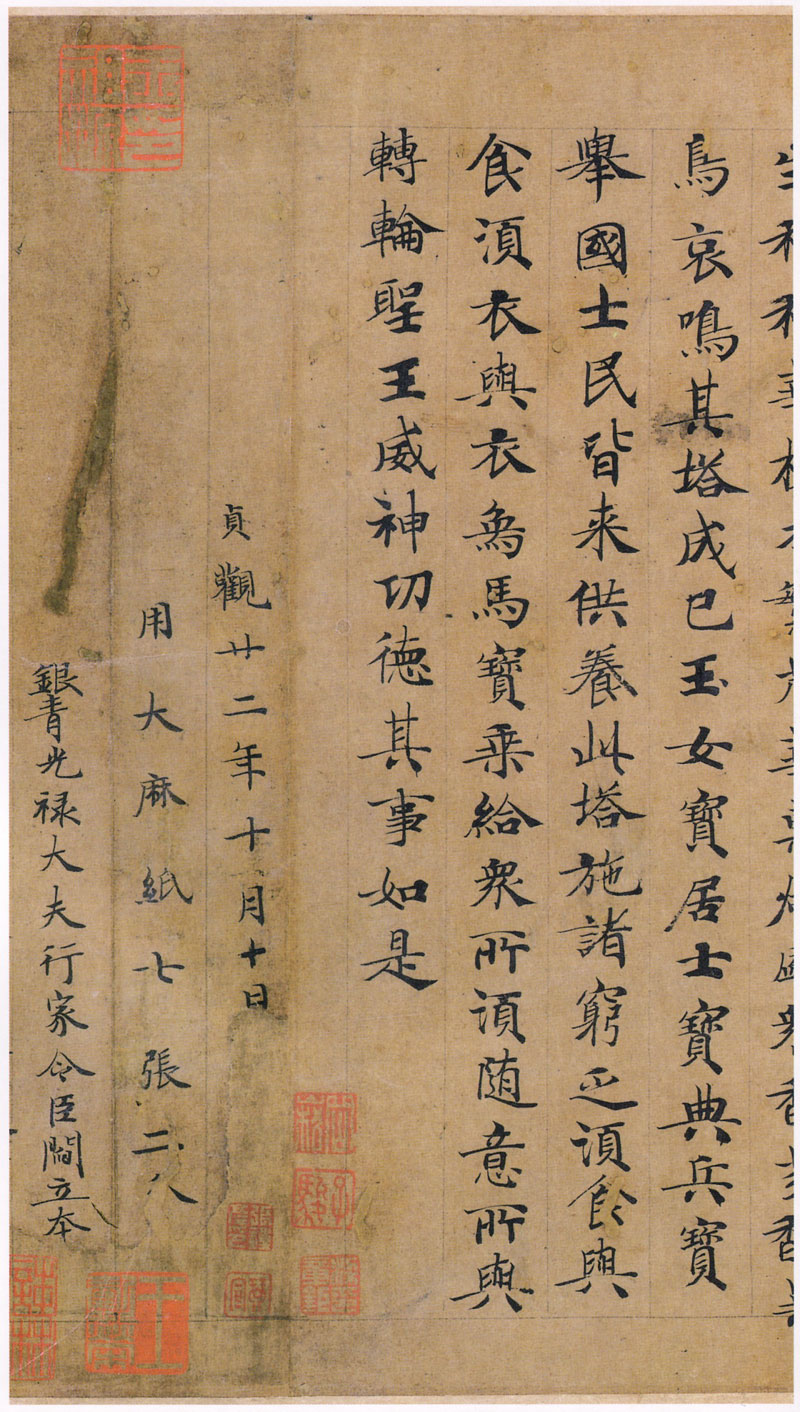

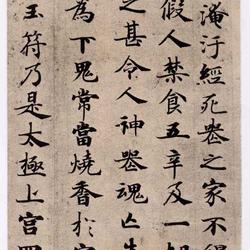

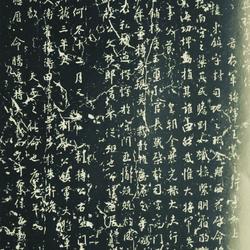

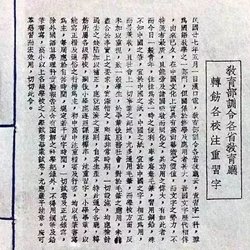

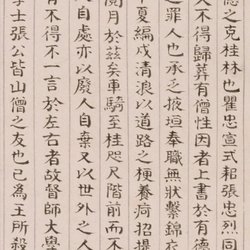

This volume of "Zhuanlun Shengxia Jing" is on paper, measuring 289.5 x 23.5 cm, with 185 lines and 17 characters. It was previously recorded in Volume 1 of Wu Rongguang's "Xin Chou's Sales of Summer Records". The inscription is "November 10th, the 22nd year of Zhenguan. Seven pieces of hemp paper are used. Silver Qingguanglu, doctor, expert, and minister Yan Liben". However, a closer look at this inscription shows that the so-called "Yin Qing Guang Lu Dafu Jian Li Ben" was added by later generations and is untrue. The calligraphy and painting dealers intended to use Yan Liben's name to increase the price of the calligraphy scroll. In addition, the name and taboo of Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty are repeatedly written in the volume, and there is no shortage of pens for the characters "世" and "民". However, this does not undermine the authenticity and reliability of the scriptures. Because according to Mr. Qi Gong's research, "the lack of stippling in taboos began in the reign of Emperor Gaozong" (see page 295 of "Qigong Manuscripts·Inscriptions and Postscripts"). This was written on November 10, the 22nd year of Zhenguan, just before Emperor Gaozong of the Tang Dynasty ascended the throne and began to avoid taboos. Therefore, it is natural and normal that there are no missing pens in it.

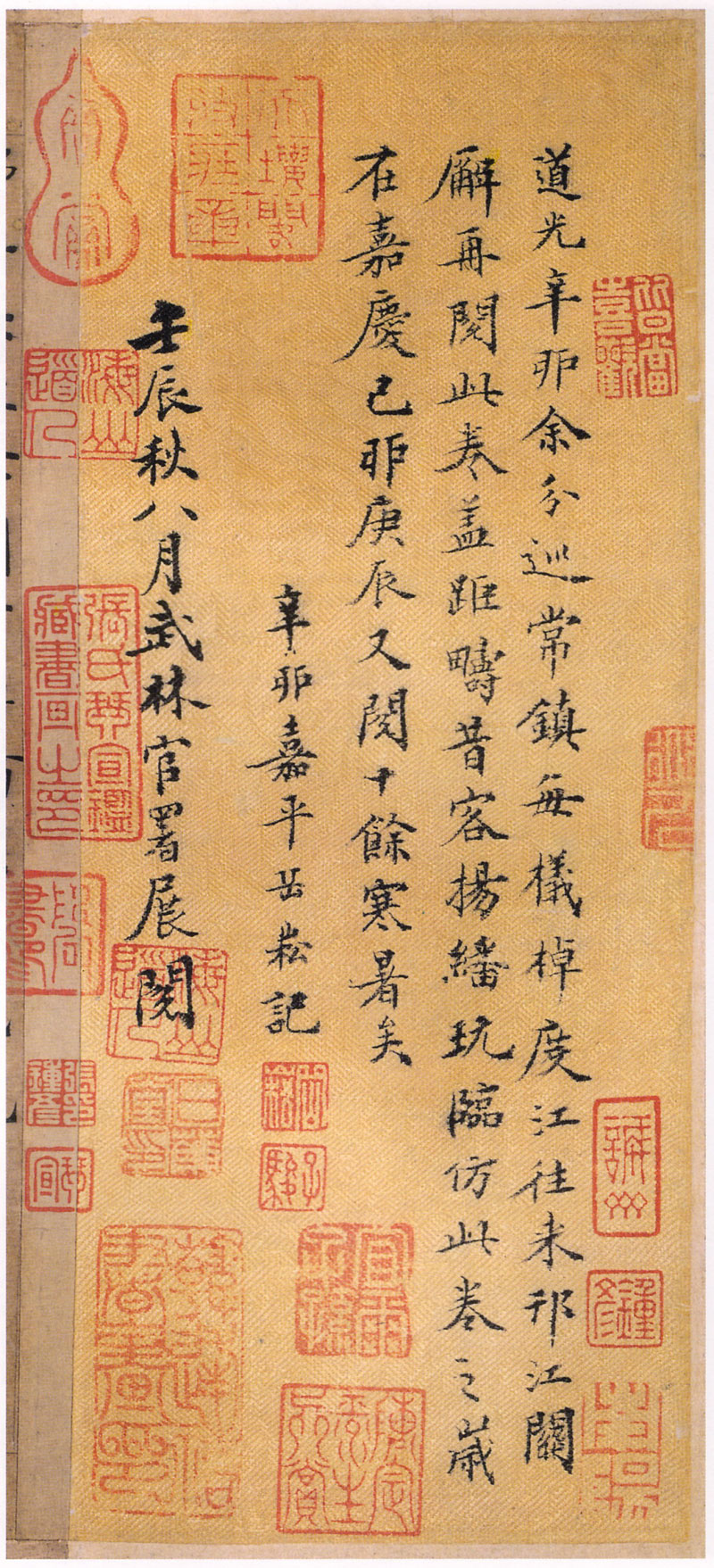

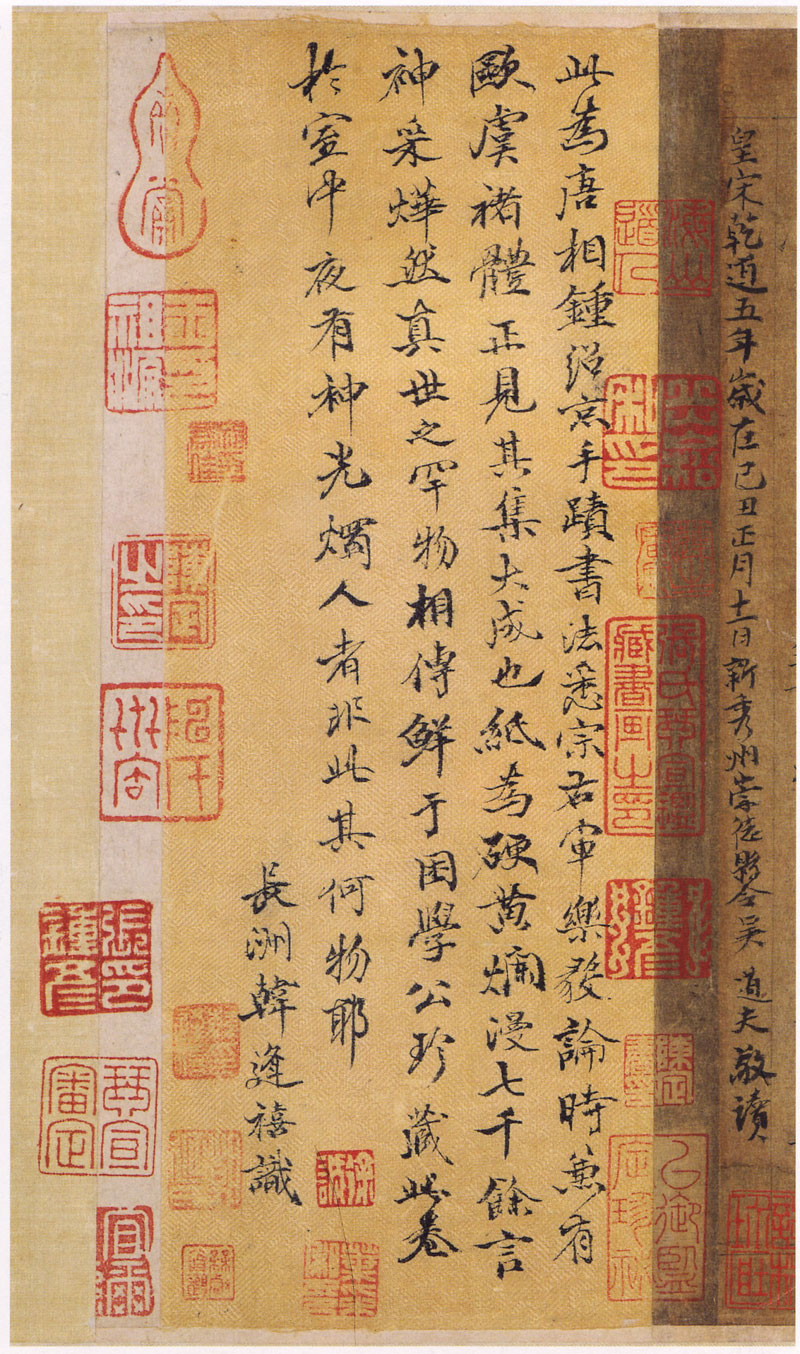

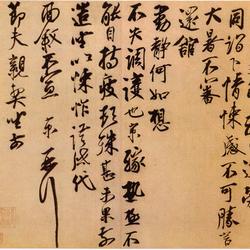

There are eighteen inscriptions and postscripts in this volume. It can be seen that there are many well-known figures who appreciate it, such as Qiu Yuan in the Yuan Dynasty, Han Fenxi in the Ming Dynasty, Liang Zhangju, Zhang Zhidong, Li Wentian, Wu Dachang, Zhao Zhiqian in the Qing Dynasty, etc. There is a postscript in the Yuan people's inscriptions that says: "... Hu Lin Sheng Biao... Qiu Yuan of Qiantang and Cao Liangshi of the same county visited Kengxue Zhai on the 11th day of the second month of Jiawu in the Yuan Dynasty." Kengxue Zhai was named Xianyu Shuzhai . Although it is difficult to determine that this object belongs to Xian Yushu's collection, it can at least be said that it was viewed by Xian Dingshu.

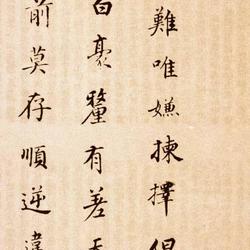

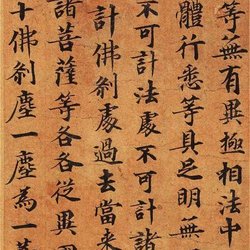

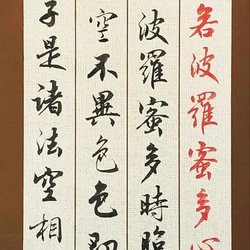

Looking at the calligraphy of this volume, it inherits the legacy of the regular regular script of the Chen and Sui Dynasties, and also incorporates the styles of the Ou and Yu styles. It is extraordinary and refined, attracting people into concentration. His brushwork is smooth and powerful, and his structure is dense and open in an appropriate manner. He is considered to be a masterpiece of sutra writing in the early Tang Dynasty, comparable to "Shan Jian Lv" and "Ling Fei Sutra". Those who study calligraphy will be enlightened and get twice the result with half the effort.

This "Chakravartin Sutra" seems to have not been included in the "Chinese Tripitaka", "Taisho Canon" and other large Buddhist collections, and the author has no research on Buddhist classics, so I feel quite reluctant in the process of reading the sentences. . In this explanation, errors are unavoidable. I sincerely hope that readers will forgive me and give me some guidance. Although its influence and popularity are not as good as "Ling Fei Jing", it is similar to the latter in at least two points: first, it has long been identified as the work of Tang Zhong Shaojing; second, it has also been engraved in series of texts (such as She in the Qing Dynasty). County Bao Shufang's "An Suxuan Dharma Notes" contains this sutra), and it was once widely circulated.

Zhong Shaojing, whose courtesy name is Keda, is said to be a descendant of Zhong Yao. He lived in the early Tang Dynasty and was over eighty when he died. People at that time called him "Xiao Zhong". There are biographies in both the new and old "Tang Shu". Song Zenggong's "Yuanfeng Lei Manuscript" said: "Shaojing's calligraphy and painting are beautiful, vigorous and methodical, but sincere and incomparable." Mi Fu's "History of Calligraphy" calls Shaojing's calligraphy "round and vigorous". However, except for the inscription on the back of the stele of the Prince Shengxian, it is almost difficult for future generations to recognize its true face in Mount Lu. As a result, some good people or profiteers claimed that some of the more outstanding Jingsheng calligraphy was the work of Zhong Shaojing.

According to Mr. Qi Gong's research, the "Ling Fei Jing" was attached to Zhong's name after Yuan Yuan Jue. I don’t know when the Sutra of the Wheel-turning Holy King was also named Zhong Shaojing, but it is certain that this is also the speculation of later generations and cannot be relied upon.

This volume of "Zhuanlun Shengxia Jing" is on paper, measuring 289.5 x 23.5 cm, with 185 lines and 17 characters. It was previously recorded in Volume 1 of Wu Rongguang's "Xin Chou's Sales of Summer Records". The inscription is "November 10th, the 22nd year of Zhenguan. Seven pieces of hemp paper are used. Silver Qingguanglu, doctor, expert, and minister Yan Liben". However, a closer look at this inscription shows that the so-called "Yin Qing Guang Lu Dafu Jian Li Ben" was added by later generations and is untrue. The calligraphy and painting dealers intended to use Yan Liben's name to increase the price of the calligraphy scroll. In addition, the name and taboo of Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty are repeatedly written in the volume, and there is no shortage of pens for the characters "世" and "民". However, this does not undermine the authenticity and reliability of the scriptures. Because according to Mr. Qi Gong's research, "the lack of stippling in taboos began in the reign of Emperor Gaozong" (see page 295 of "Qigong Manuscripts·Inscriptions and Postscripts"). This was written on November 10, the 22nd year of Zhenguan, just before Emperor Gaozong of the Tang Dynasty ascended the throne and began to avoid taboos. Therefore, it is natural and normal that there are no missing pens in it.

There are eighteen inscriptions and postscripts in this volume. It can be seen that there are many well-known figures who appreciate it, such as Qiu Yuan in the Yuan Dynasty, Han Fenxi in the Ming Dynasty, Liang Zhangju, Zhang Zhidong, Li Wentian, Wu Dachang, Zhao Zhiqian in the Qing Dynasty, etc. There is a postscript in the Yuan people's inscriptions that says: "... Hu Lin Sheng Biao... Qiu Yuan of Qiantang and Cao Liangshi of the same county visited Kengxue Zhai on the 11th day of the second month of Jiawu in the Yuan Dynasty." Kengxue Zhai was named Xianyu Shuzhai . Although it is difficult to determine that this object belongs to Xian Yushu's collection, it can at least be said that it was viewed by Xian Dingshu.

Looking at the calligraphy of this volume, it inherits the legacy of the regular regular script of the Chen and Sui Dynasties, and also incorporates the styles of the Ou and Yu styles. It is extraordinary and refined, attracting people into concentration. His brushwork is smooth and powerful, and his structure is dense and open in an appropriate manner. He is considered to be a masterpiece of sutra writing in the early Tang Dynasty, comparable to "Shan Jian Lv" and "Ling Fei Sutra". Those who study calligraphy will be enlightened and get twice the result with half the effort.

This "Chakravartin Sutra" seems to have not been included in the "Chinese Tripitaka", "Taisho Canon" and other large Buddhist collections, and the author has no research on Buddhist classics, so I feel quite reluctant in the process of reading the sentences . . In this explanation, errors are unavoidable. I sincerely hope that readers will forgive me and give me some guidance.