Liu Gongquan

Liu Gongquan (778-865), courtesy name Chengxuan, was born in Huayuan, Jingzhao (now Yaoxian County, Shaanxi Province). Emperor Daizong of the Tang Dynasty was born in a family of officials in Wuwu, the thirteenth year of the Dali calendar (778). His grandfather, Liu Zhengli, once served as a scholar in Pizhou (governing in today's Pi County, Shaanxi Province) and joined the army. His father, Liu Ziwen, served as governor of Danzhou (governed in present-day Yichuan, Shaanxi Province). Gong Quan "has a passion for learning since he was a child, and he can write poems at the age of twelve". Xianzong "became a Jinshi at the beginning of the Yuan Dynasty. He was Shi Brown's Secretary and Provincial School Secretary" and embarked on an official career.

Liu Gongquan's career as a school secretary lasted ten years. During this period, he wrote many calligraphy works while studying, including classics written for Buddhist temples and tablets written on invitations. Currently, it is known that Liu Gongquan's earliest calligraphy work "Repeat Liuzhou Dayun Temple" was written in Yuan Dynasty. It was written at the invitation of clan member Liu Zongyuan in the twelfth year of his reign. These calligraphy works of Liu Gongquan gave him the opportunity to serve as a calligrapher for the rest of his life.

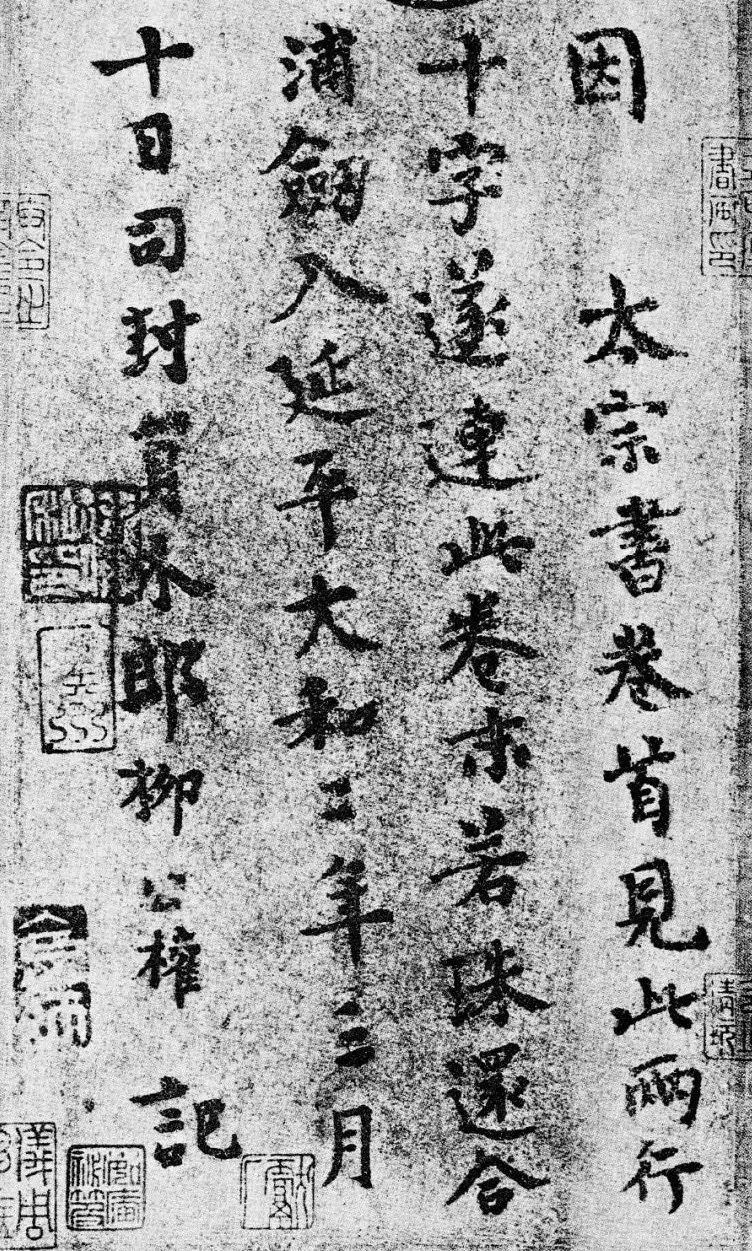

In May of the 14th year of Yuanhe (819), Liu Gongquan was appointed as a staff member and secretary by Li Tingpi, a friend of his brother Liu Gongchuo, the governor of Xiazhou (governed near Hengshan, Shaanxi today) and the governor of Xia Suiyinqing, and he left Beijing to take up his post. Not long after, in March of the 15th year of Yuanhe (820), Liu Gongquan went to Beijing to perform an official mission and was summoned by Mu Zong, who had just ascended the throne. Mu Zong greatly praised his calligraphy and said: "I saw your handwriting in a Buddhist temple and thought about it for a long time. ." That day he paid homage to you and entered the Hanlin Academy to serve as a bachelor of calligraphy. Serving the emperor may seem like an honor, but his status in the court is very low, similar to that of an artist or craftsman. The emperor summoned Liu Gongquan to the palace to serve as a servant. Initially, it was just for convenience, not for artistic needs. Mu Zong's call for public authority to write a book was probably an occasional matter.

"Old Book of Tang·Biography of Liu Gongquan" records: Mu Zong was secluded in politics. He asked Gongquan how good his pen was, and he replied: "Use your pen with your heart in mind, and if your heart is upright, your pen will be straight."

This record was praised by Qianqiu as "bi admonishing Mu Zong". In fact, Liu Gongquan is not answering the wrong question here, but what he is talking about is the natural principle of calligraphy. Mu Zong's misunderstanding caused Liu Gongquan to be ignored. According to the regular system, if a bachelor "is one year old after being admitted to the hospital, he will move to know the imperial edict and prepare the imperial edict. Those who do not know how to prepare the imperial edict will not write documents." Liu Gongquan had been in the Hanlin Academy for four years and was still just a scholar. After Mu Zong's death, Liu Gongquan left the Hanlin Academy and became a living minister. In May of the second year of Emperor Wenzong's reign (828), Liu Gongquan was ordered to enter the Hanlin Academy for the second time. Unfortunately, three years later, he was still a servant with no taste and was not even qualified to draft documents. In desperation, he had no choice but to ask his brother Liu Gongchuo, a senior official, to ask Prime Minister Li Zongmin for help. Liu Gongchuo wrote to Li Zongmin, saying: "My younger brother has worked hard on his art of diction, and he was very useful in serving as a calligrapher in the previous dynasty. He worked together and blessed him a lot. He is really ashamed of it and begged for a chance to change his rank." Thanks to Li Zongmin's power, Liu Gongquan became more powerful in the Yamato Five Dynasties. In July of that year, he was changed to Yousi Langzhong and released from the Hanlin Academy.

The biggest turning point in Liu Gongquan's life came when he entered the Hanlin Academy for the third time in October of the eighth year of Yamato as a bachelor of scholar's books. The first two times he served as a scholar, he was ignored, but this time he was favored, and his favor increased day by day: in the next year, he moved to Zhizhizhi, served as a bachelor, and concurrently served as a scholar. In the first year of Kaicheng (836), he moved to Zhongshushe. In the second year, he was promoted to admonish the officials. In the third year, he was moved to the minister of the Ministry of Industry. Although he still serves as a bookkeeper, his status is completely different from that of Gong and Zhu.

Liu Gongquan's treatment when he entered the Hanlin Academy for the third time was completely different from the first two times. Not only did he receive more favors, but Wenzong often talked with him about poetry and calligraphy. "Old Tang Book: Biography of Liu Gongquan" records:

Every time he was called to the bathhouse, he saw the postscript following the candle. He still had not finished his words and did not want to take the candle, so the palace attendants used wax to tear up paper and crumpled it. (The second year of Kaicheng) From the Xingweiyang Palace Garden, the resident chariot said to Gongquan: "I have a happy event, and I will give you a coat. It has been a long time coming. I will give you spring clothes in February this year." Congratulations were given in front of Gongquan. It said: "The single greetings are not over yet, you can congratulate me with a poem." The palace servants forced him to speak, and Gongquan responded: "Although there was no war last year, I have not returned this year. How can I repay the emperor's kindness? In the spring, I will get spring clothes. "Shang Yue, appreciate it for a long time."

Wenzong's summer couplet with the bachelor. The emperor said: "Everyone suffers from the heat, but I love the long summer." Gongquan continued: "The smoke wind comes from the south, and the palaces and pavilions are slightly cool." The five bachelors of the time, Ding (Ju Hui) and Yuan (Yu), all belonged to the same family. After that, the emperor only satirized Gongquan in two sentences, saying: "The clear meaning of the speech is enough, and it is rare to get it." He ordered Gongquan to write an inscription on the wall of the palace with a radius of five inches. The emperor looked at it and sighed: "Zhong, the king is alive again. There’s nothing more to add!”

Liu Gongquan's calligraphy often brought a little happiness to the miserable Wenzong, so it was natural that he received special favor from Wenzong. This was true in the Wenzong Dynasty, and it was also true in the Wuzong, Xuanzong, and Yizong dynasties after Wenzong:

Emperor Wuzong was angry with a concubine, and after a long time, he summoned her again. Addressing Gong Quan, he said: "I blame this person. If I get a bachelor's degree, I will be relieved." Gong Quan did not hesitate to think about it and said: "Regardless of the past, I have disobeyed the Lord's kindness and have been willing to guard the long gate alone. At present, But with the king's attention, I went back to the pepper room to wipe away the traces of tears." I went to Dayue and gave him two hundred pieces of brocade and ordered the palace people to come forward and thank him.

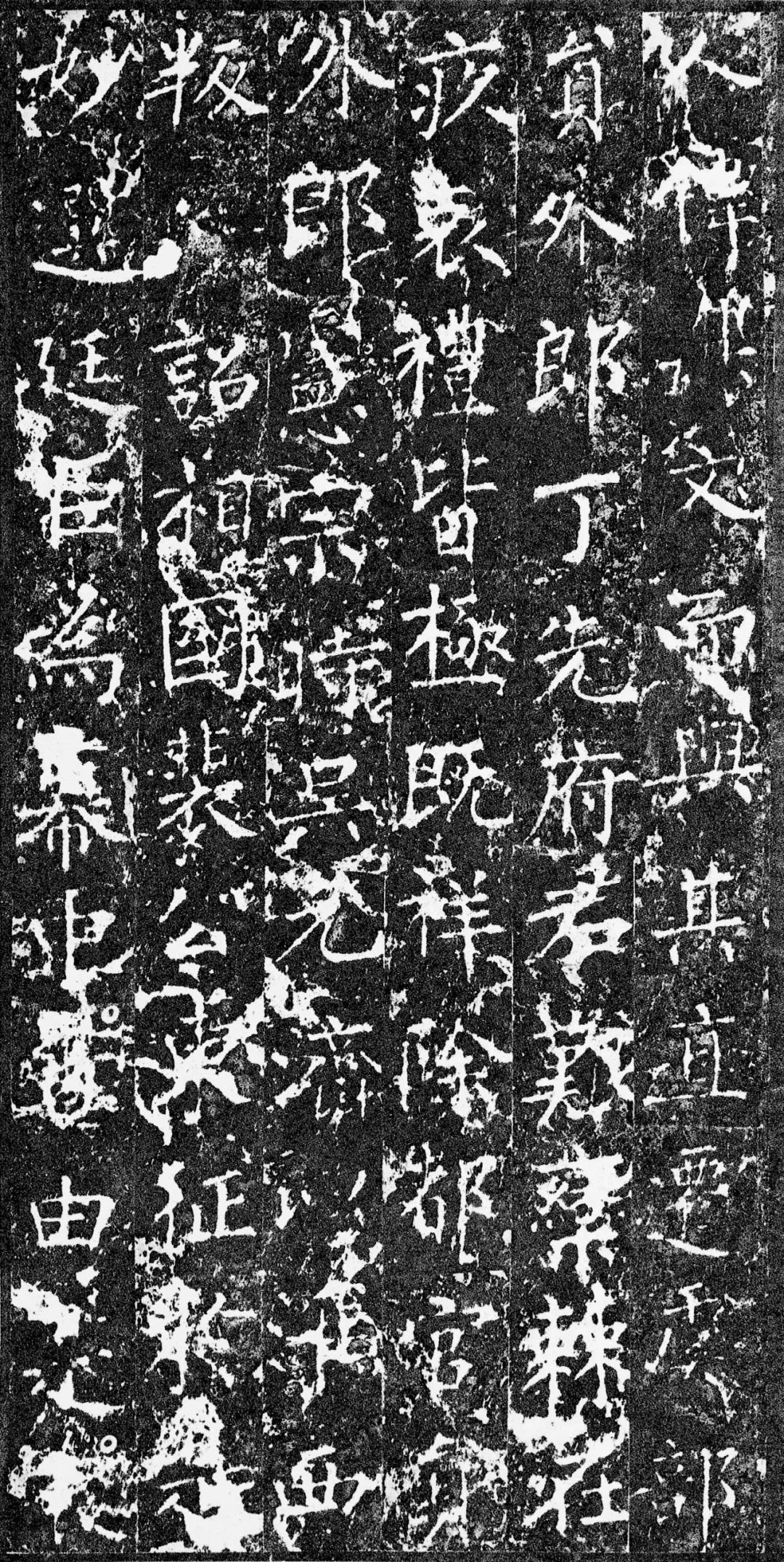

At the beginning of junior high school, he transferred to the junior division and passed the exam. Xuanzong was summoned to the palace and wrote three letters to the emperor. Ximen Jixuan, the military envoy, held an inkstone, and Cui Juyuan, the privy envoy, wrote the pen. A piece of paper with a cross written in real calligraphy said: "Mrs. Wei passed down the writing technique to Wang Youjun"; a piece of paper written in cursive script with eleven characters said: "Yong Chan Master Yong's Zhencao "Thousand Character Essay" was used to obtain the family method"; a piece of paper written in cursive eight characters said: "Predicate It’s okay to help.” He was given brocade vases, plates and other silverware, but he still ordered him to write a letter of thanks, regardless of his true deeds. The emperor especially cherished it.

During the three dynasties of Wuzong, Xuanzong, and Yizong, Liu Gongquan's official rank was promoted from the third rank to the second rank. In the sixth year of Xiantong (865), he died at the age of eighty-eight and was awarded the posthumous title of Grand Master to the Crown Prince, which was a great honor.

"At that time, public officials and ministers were not allowed to write steles with public authority. People thought it was unfilial. When foreign barbarians paid tribute, they were all signed with goods and shells, saying that they were buying Liu Shu." What is described here should be Liu Gongquan's third time entering the Hanlin Academy and his official career. The situation after success. Eight years ago, Liu Gongquan's status was low. Even if his calligraphy skills were superb, I am afraid that his calligraphy would not become a fashionable social pet, let alone have such an important relationship with "filial piety".

We can also see this from the calligraphy works of Liu Gongquan recorded in the literature of the Song Dynasty. In the early years of Yuanhe (806), Liu Gongquan lived in the capital and began his calligraphy career. In the nearly thirty years to the eighth year of Yamato (834), he created There are only a dozen epitaphs written on tablets, but more than 70 epitaphs were written in the thirty years after the first year of Kaicheng (836). Although this is not all of Liu Gongquan's calligraphy works, this disparity in quantity is certainly in line with historical reality.

In the three dynasties of Wuzong, Xuanzong and Yizong, Liu Gongquan successively served as a regular servant of Yousanqi, a bachelor and academician of Jixian Palace, Prince Zhanshi, Prince Guest Minister of the Ministry of Civil Affairs, Prince Shaofu, and Prince Shaoshi. From the sixth year of Xiantong (865) At the age of eighty-eight, he died in the position of Prince's Young Master and was posthumously awarded the title of Prince's Grand Master. As an important member of the court of the late Tang Dynasty, he was unknown, unlike Yan Zhenqing who spent his heroic life vigorously on the ever-changing political stage. He aspired to study calligraphy, devoted himself to the art of calligraphy, and devoted his whole life to erecting a monument comparable to Yan Zhenqing in the palace of calligraphy art, which will be admired by future generations.

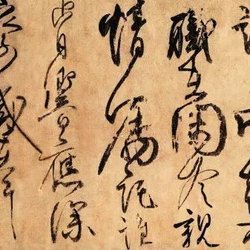

Liu Gongquan's calligraphy career began around the Zhenyuan period. He wrote many works throughout his life, but unfortunately, most of them have been lost. There are only about 20 works that have been handed down to this day. Among them, the only ink that can be confirmed to be Liu Gongquan's calligraphy is the "Postscript of "Sending Lishu", which contains more than 20 words.

"Postscript to "Pear Sending Note"

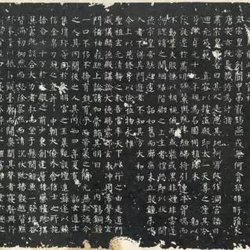

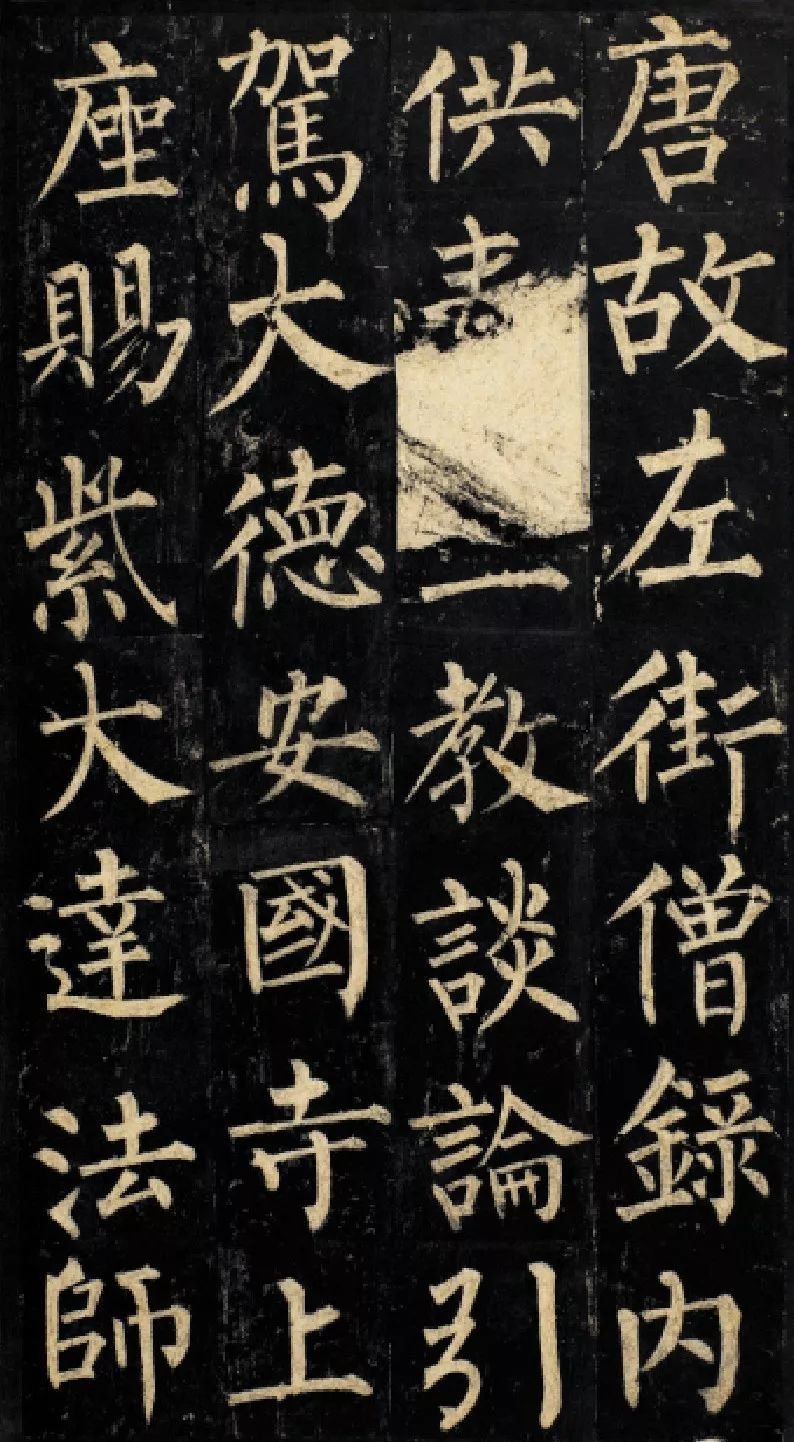

There are only thirteen rubbings on the stele, and there are also forgeries mixed in among them:

"Li Sheng Monument"

"Li Sheng Stele" has been rewritten and reengraved by later generations and is no longer authentic;

"Fu Lin Monument"

"Fulin Stele" is forged from the inscription to the calligraphy;

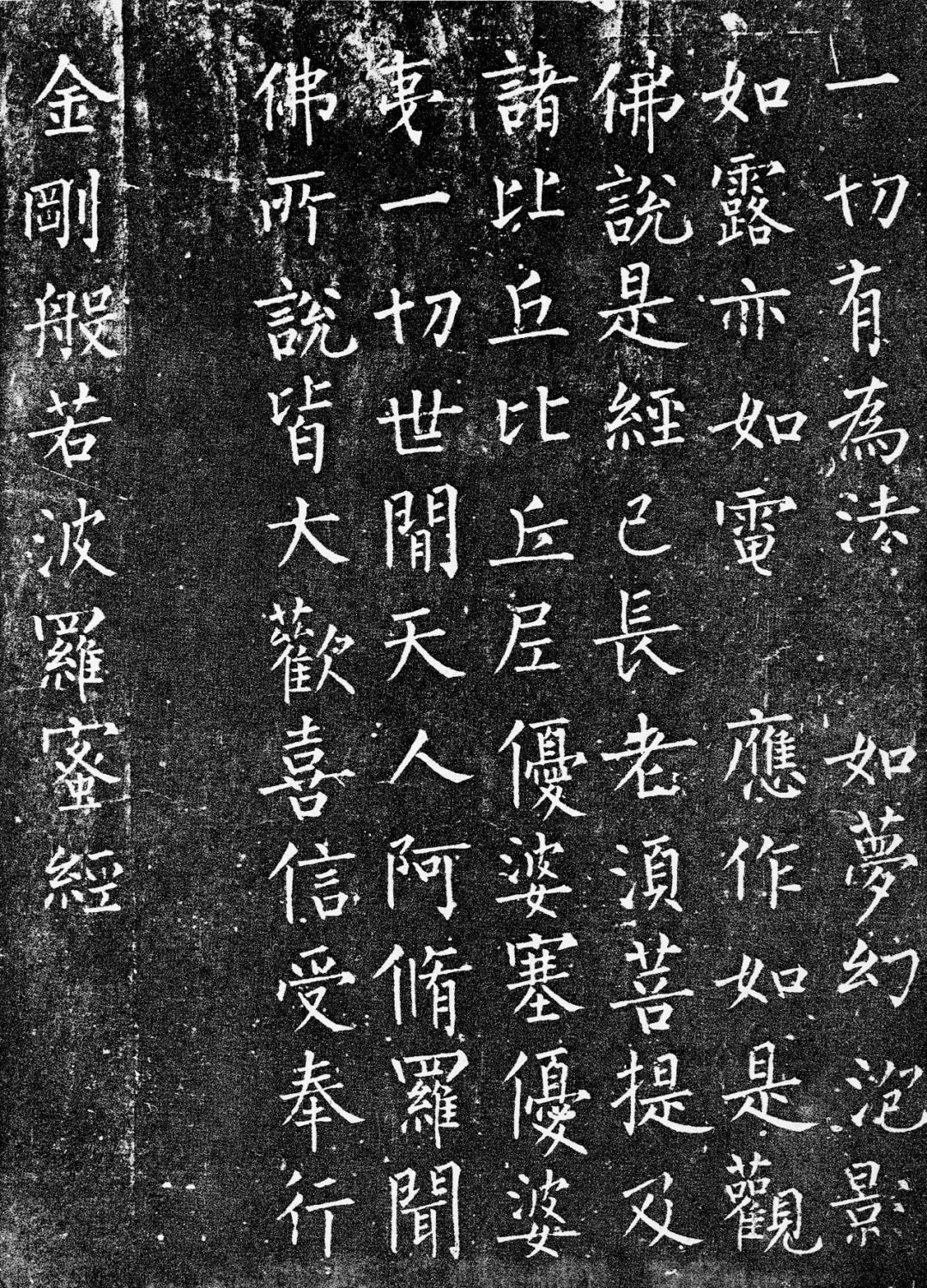

"Diamond Sutra"

"Sutra for Eliminating Disasters and Protecting Life"

The Diamond Sutra, the Sutra for Eliminating Disasters and Protecting Life, and the Inscription on the Ring Pagoda of Fulin Temple are all forged by later generations.

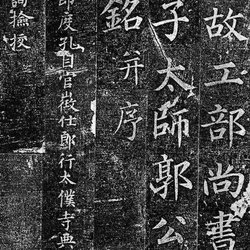

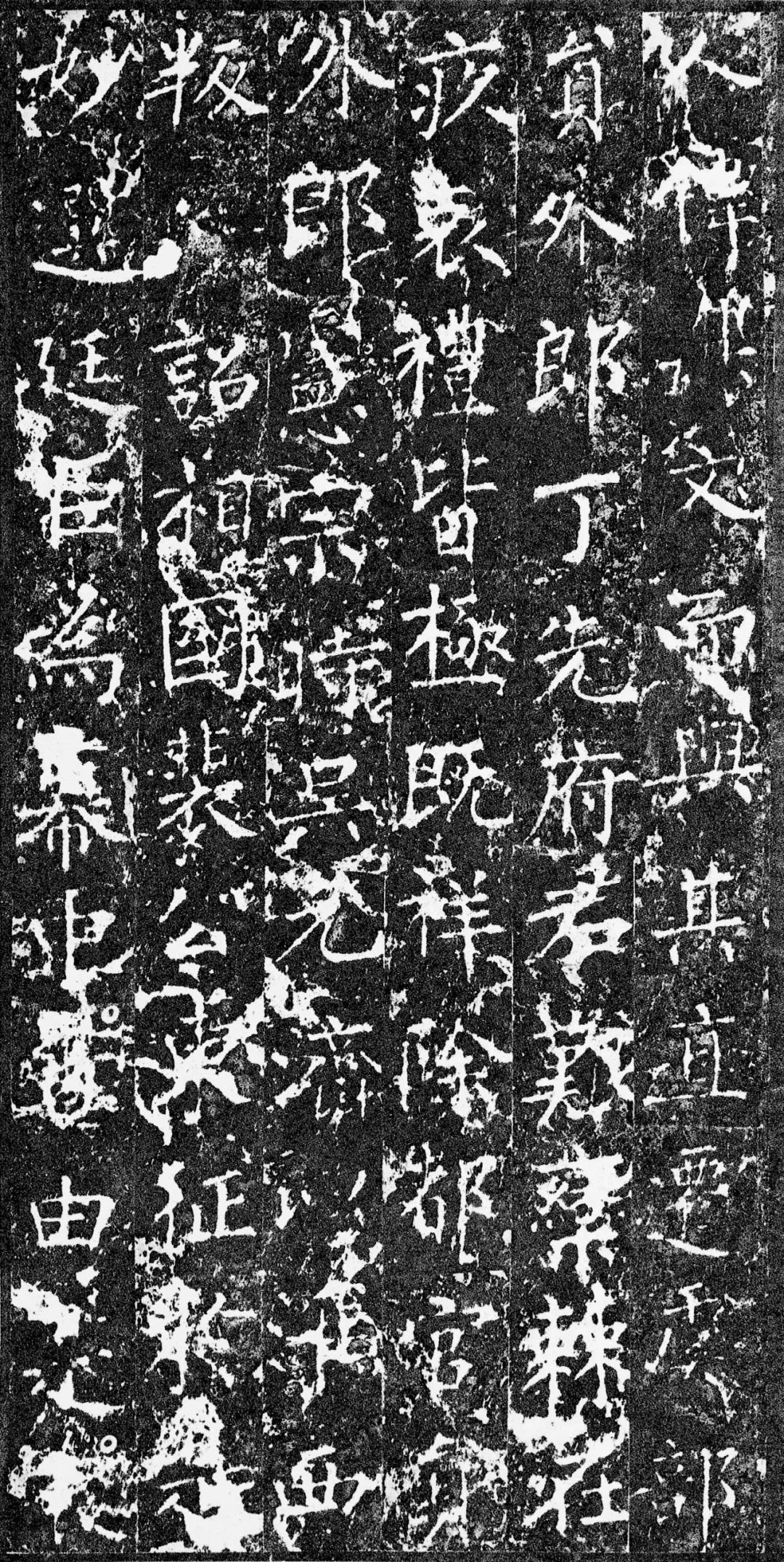

"Stele of Feng Su, Minister of Official Affairs"

"Bell Tower Inscription"

The only tablets Liu Gongquan wrote before he was sixty years old were the "Stele of Feng Su, Minister of the Ministry of Official Affairs" and the "Inscription on the Bell Tower", and the writing time was limited to the two years between the age of fifty-nine and sixty.

According to the only available data, Liu Gongquan's calligraphy can be divided into two periods: the early period before the age of 60, and the later period after the age of 60. The main feature of early calligraphy is the collection of ancient works. The so-called collection of ancient calligraphy means that calligraphy has not yet formed its own form, and most of the characters written in the pen come from the ancient inscriptions and inscriptions learned - the ancient people's calligraphy is collected and written into calligraphy works. "Old Tang Book: Biography of Liu Gongquan" records:

Gong Quan was a beginner in Wang Shu, and had read all over modern calligraphy. His style was vigorous and charming, and he was in a class of his own. …

The "Diamond Sutra Stele" of Ximing Temple in Shangdu (i.e. Chang'an) has the styles of Zhong (Yao), Wang (Xizhi), Ou (Yang Xun), Yu (Shinan), Chu (Suiliang), and Lu (Cambodian), especially proud.

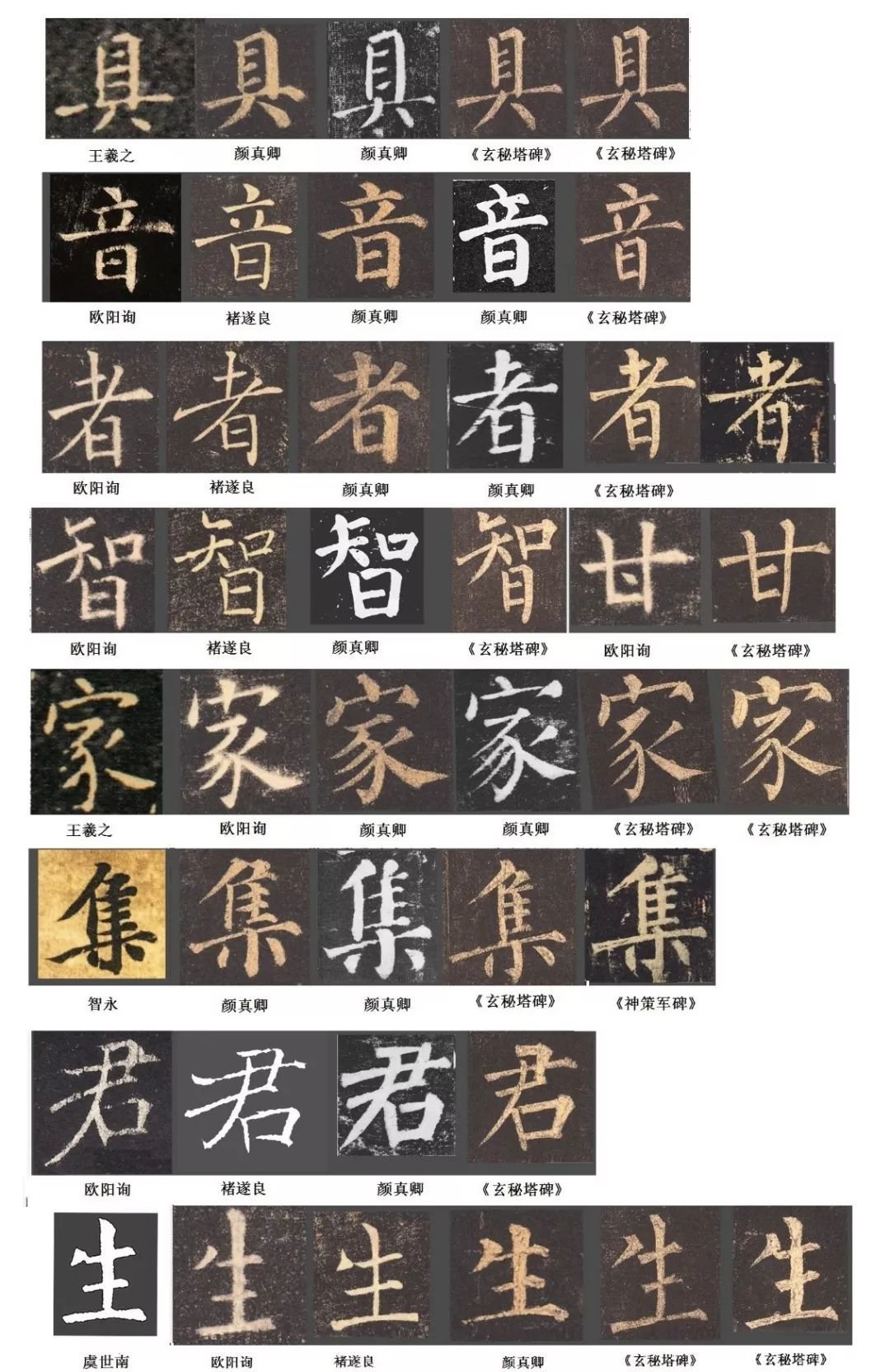

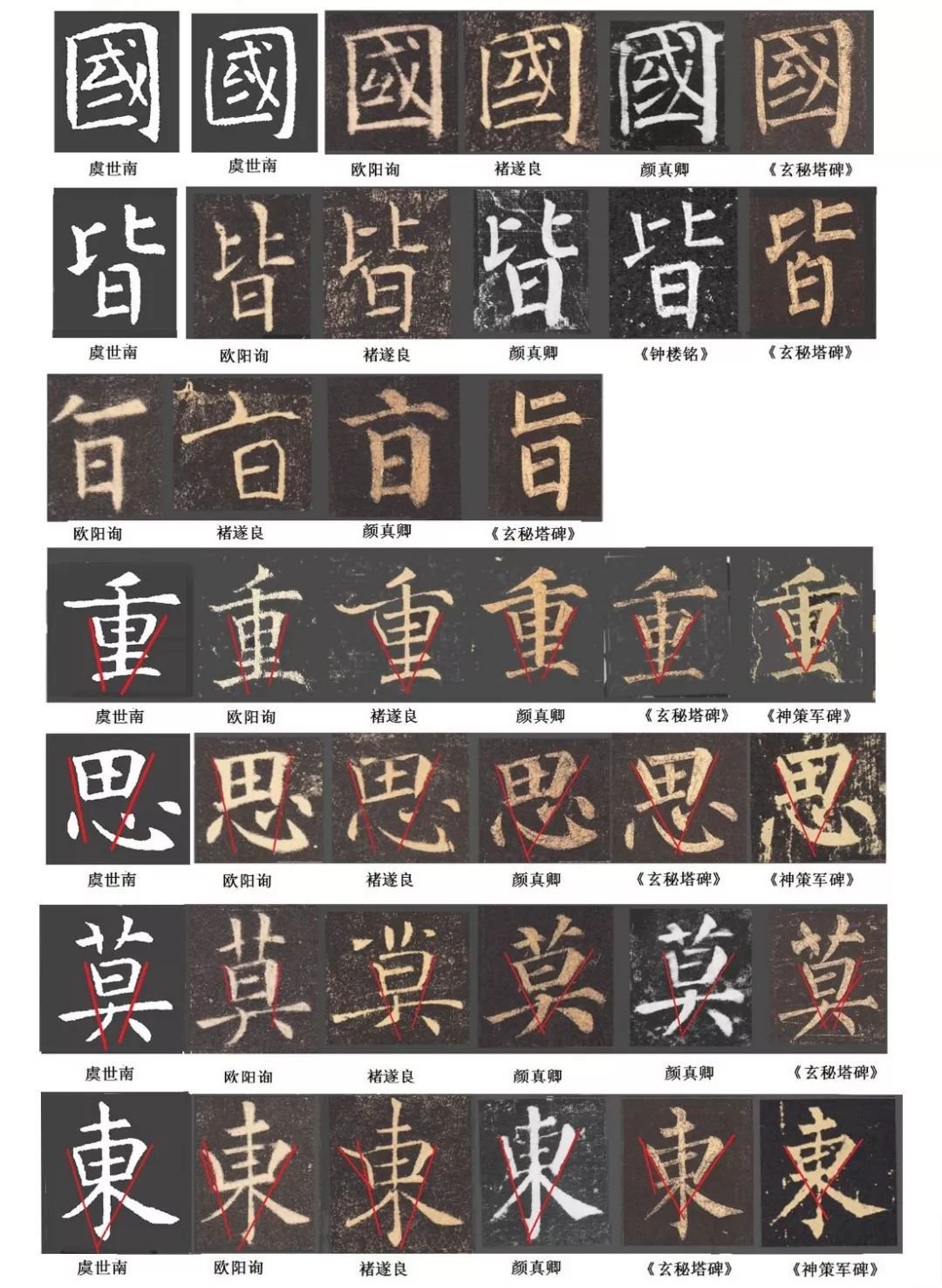

It can be seen from this record that Liu Gongquan started his calligraphy practice from Wang Xizhi, and he learned from a wide range of calligraphers. Various calligraphy masters in the Wei, Jin and early Tang Dynasties were models for him to learn from. Although the so-called "modern calligraphy" does not specify which ones it belongs to, judging from the calligraphy characteristics of Ximing Temple's "Diamond Sutra Stele" mentioned in the article, they are mainly Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang, and Lu Jian.

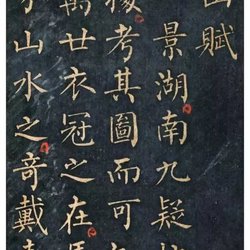

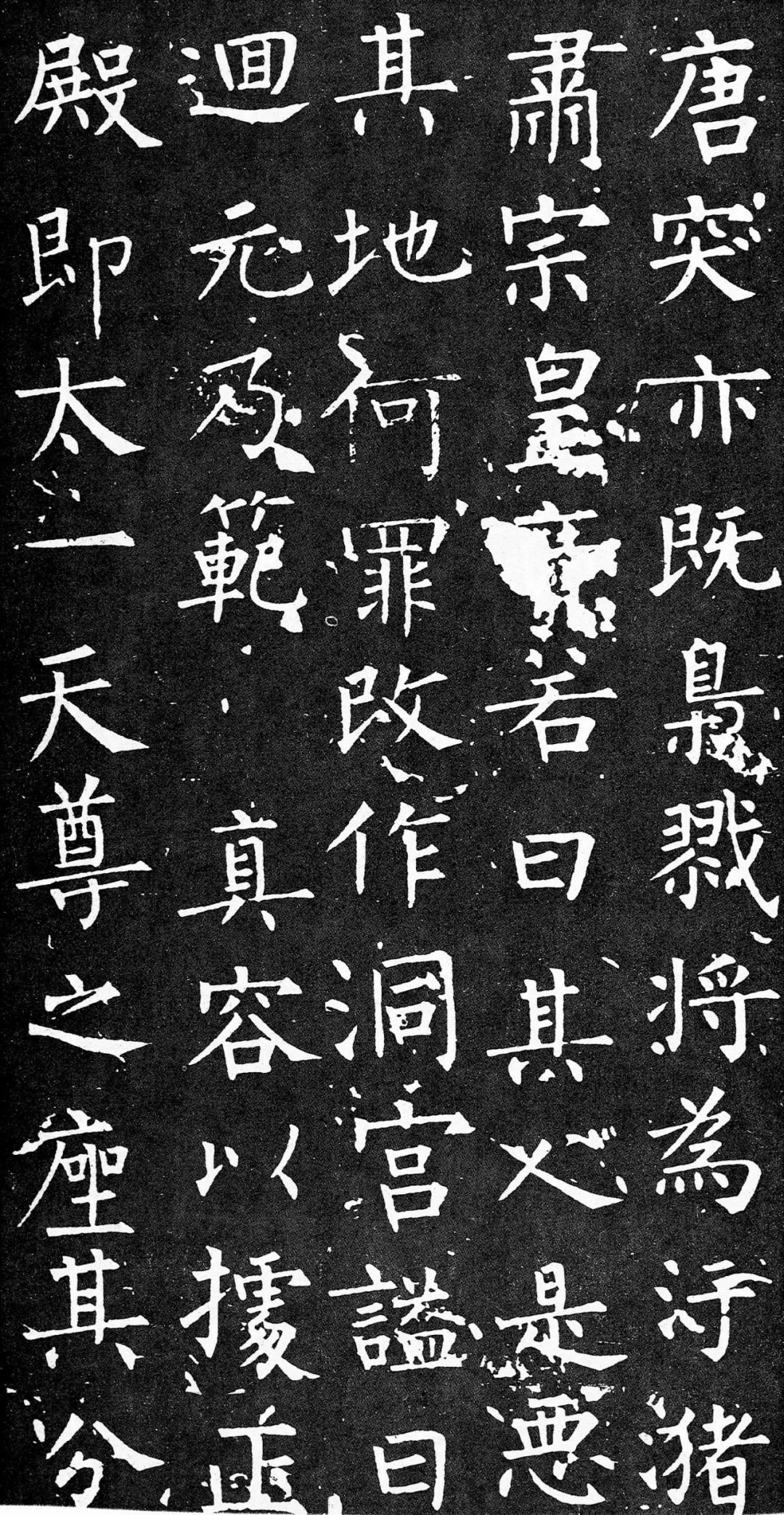

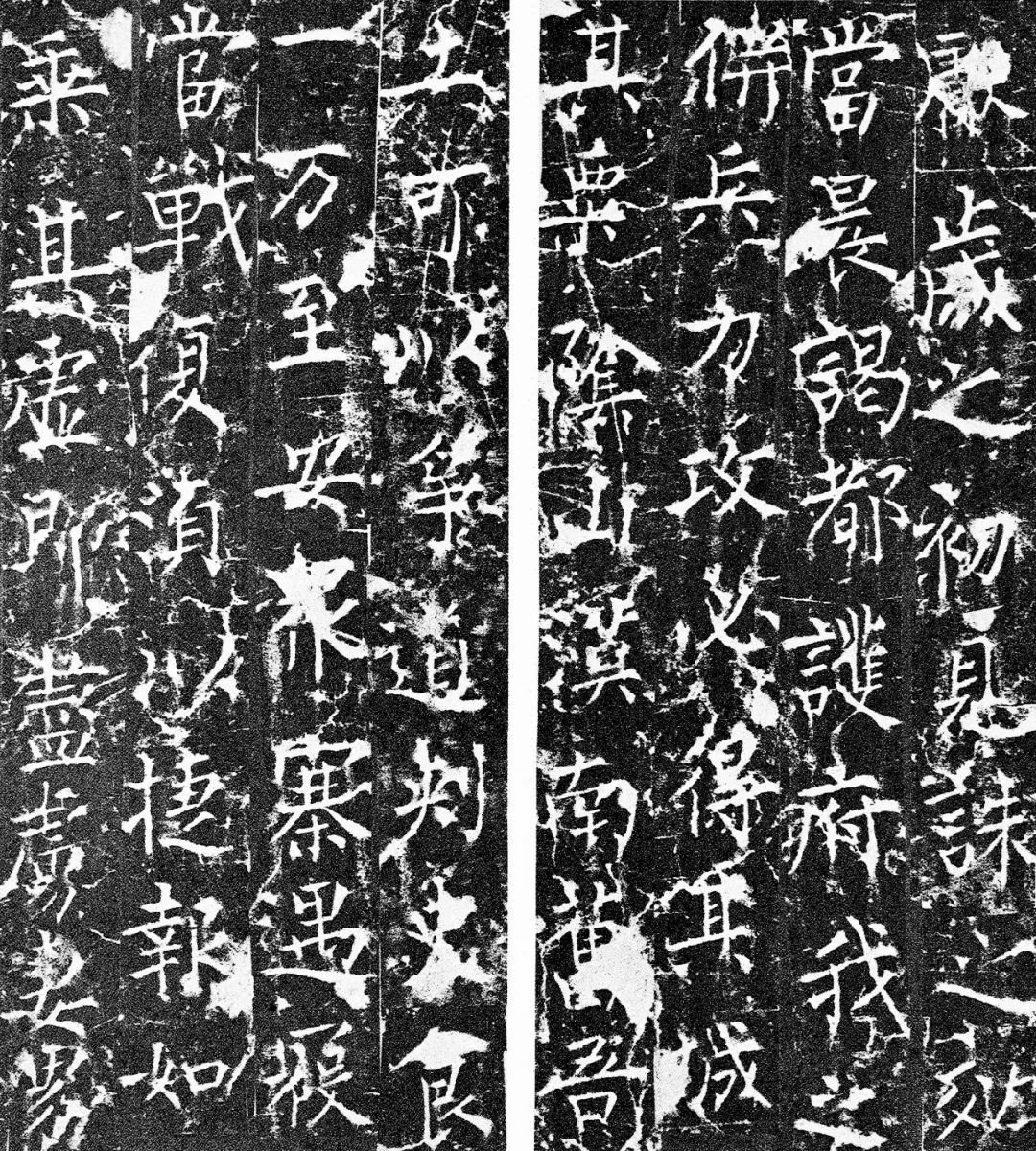

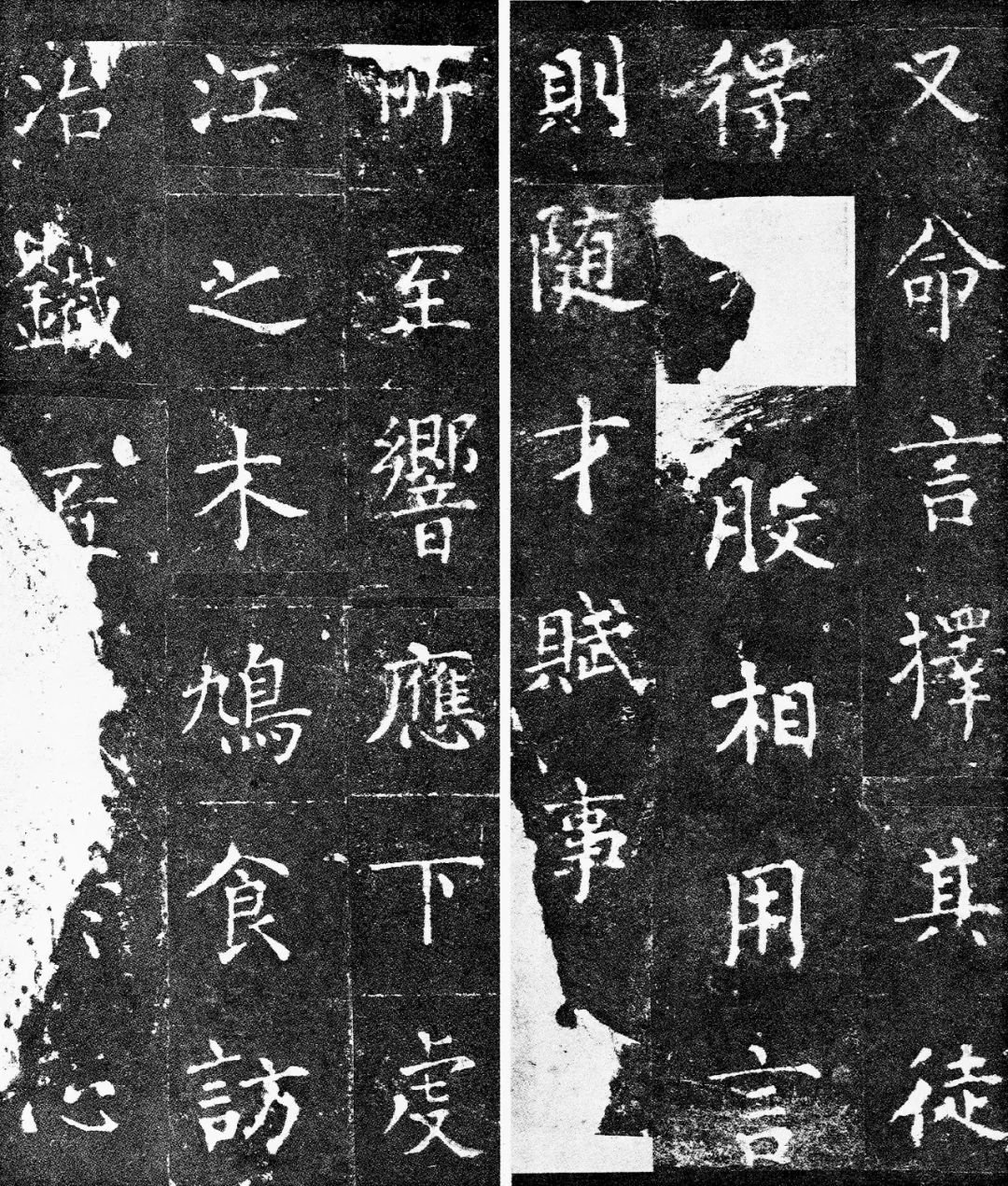

"Bell Tower Inscription"

From the "Bell Tower Inscription" we can still see the "preparation" of Liu Gongquan's calligraphy works - the characteristics of collecting ancient works. "The Bell Tower Inscription" was written in April of the first year of Kaicheng (836), when Liu Gongquan was fifty-nine years old. The small regular script of the first five lines of this work sometimes contains the postures of Zhong Yao and Wang Xizhi. The structure of the inscriptions such as "Xuan", "Guan", "Chao", "Da" and "Yin" can all be found in Wang Xizhi, Yu Shinan, Ouyang Xun The ancestral copy was found by calligraphers of previous generations such as Chu Suiliang and Yan Zhenqing, and the structure and shape are almost the same. In this work, the physical postures of Yu Shinan and Lu Jianzhi are no longer visible, and the combination of many characters has become Liu Gongquan’s personal appearance. Although the brushwork of the whole work is unified and very thin, hard and sharp, due to the diverse body shapes, the composition is not harmonious and slightly scattered.

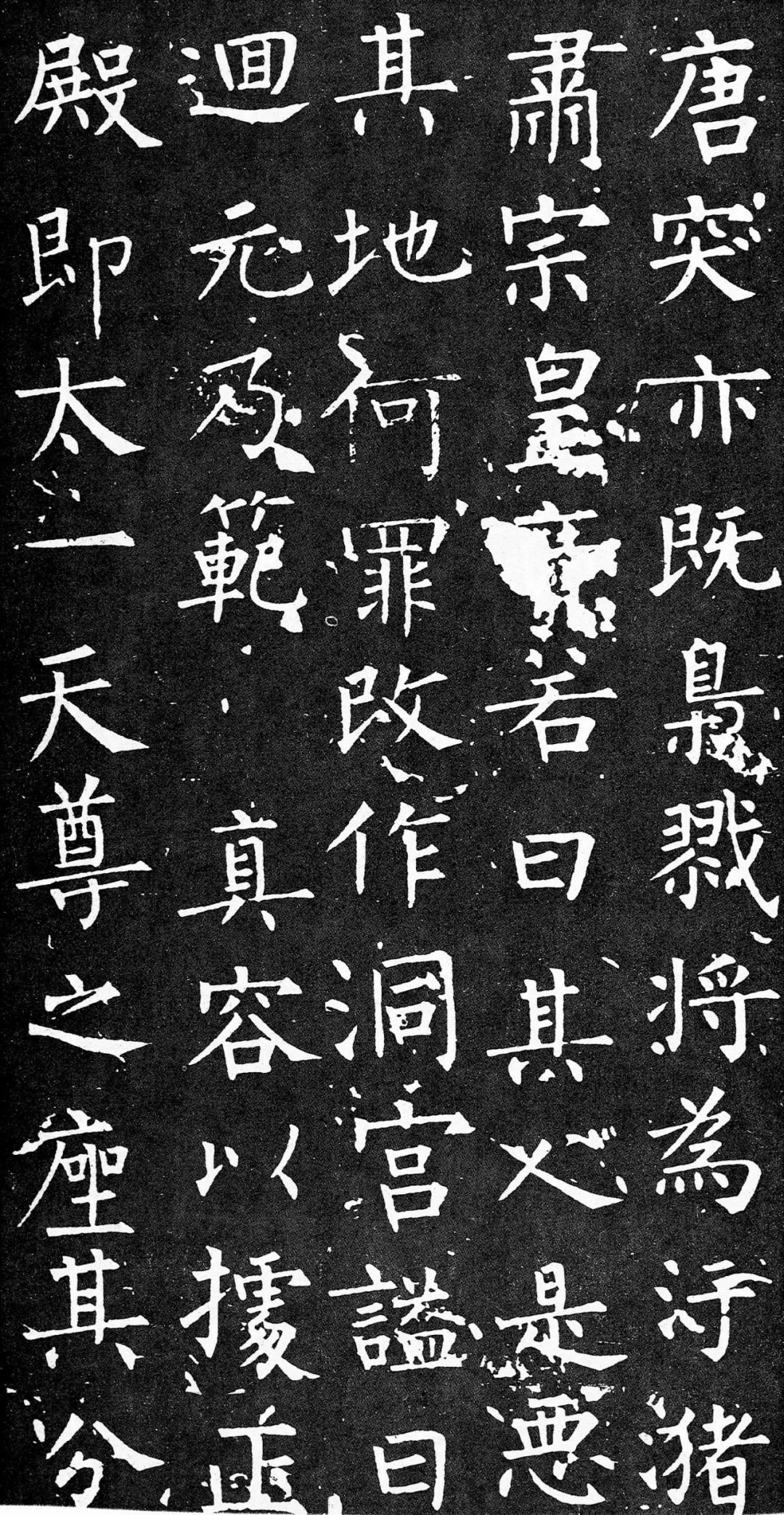

"Stele of Feng Su, Minister of Official Affairs"

The "Stele of Feng Su, Minister of the Ministry of Civil Affairs" written at the age of sixty (the second year of Kaicheng) was written on the eve of Liu Gongquan's death. The roundness of the writing style of "Feng Su Bei" is quite similar to that of Yu Shinan. Although the structure is still relatively broad and straight, it is no longer like the "Bell Tower Inscription", which can be found in the calligraphy of various calligraphy schools in the Jin and Tang Dynasties. If the "Bell Tower Inscription" is like a house full of guests, although the emotions are harmonious, but the faces are different, they are not a family, then the "Feng Su Bei" is like a gathering of brothers, with very similar faces, expressions, and gestures, which is very harmonious.

Going back from this, we can make the following prediction: Liu Gongquan's early calligraphy was probably "no character has no origin", and it was his later calligraphy that truly showed his personal style.

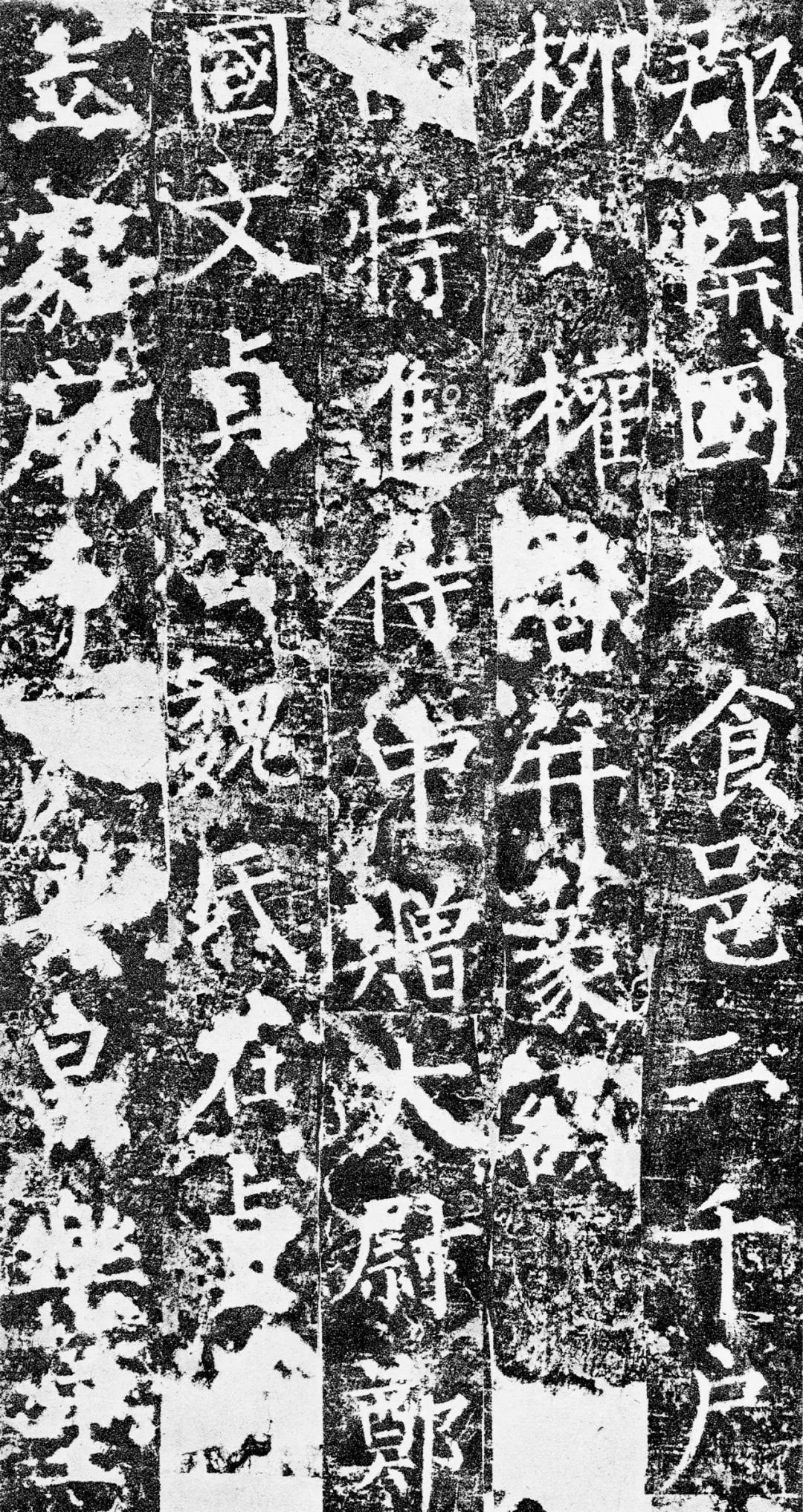

There are currently only seven regular script works created by Liu Gongquan in his later years that can be identified:

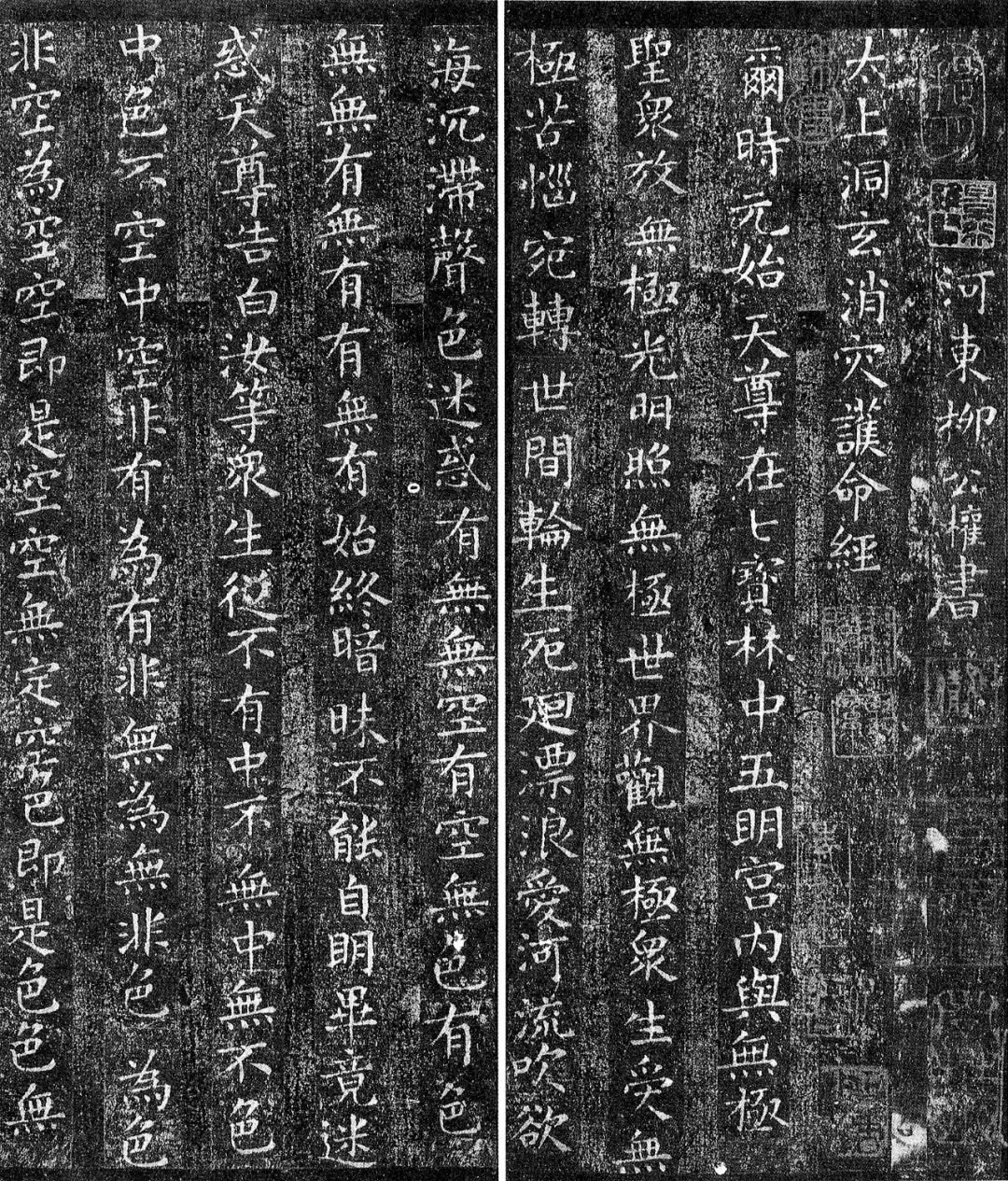

1. "Tai Shang Lao Jun's Sutra of Everlasting Peace" (written five years after its founding, at the age of sixty-three, in small regular script)

2. "Master Dada's Mysterious Pagoda Stele" (written in regular script at the age of sixty-four, the first year of Huichang)

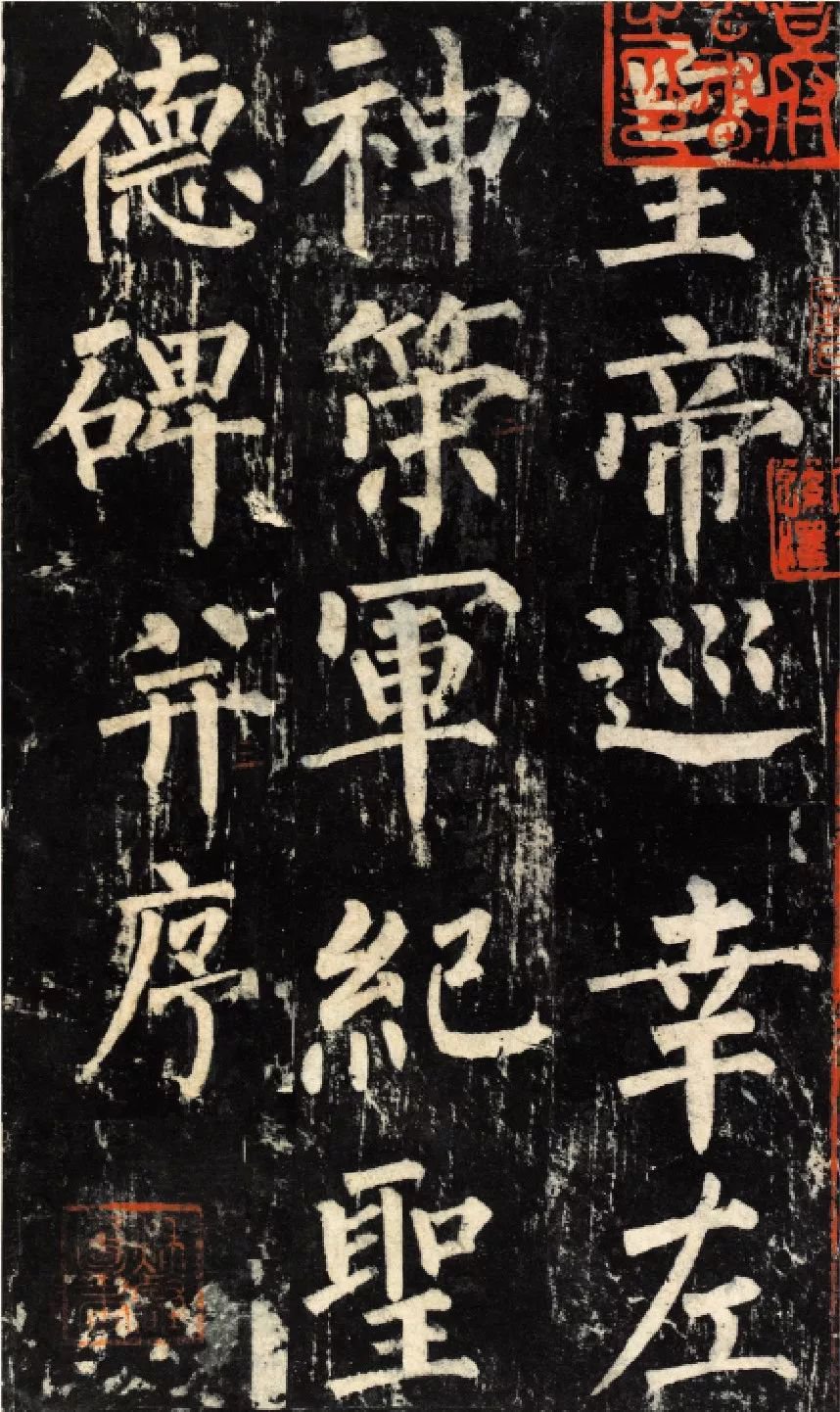

3. "The Monument of the Emperor's Visit to the Zuo Shence Army to Commemorate the Holy Virtue" (written in regular script at the age of sixty-six in the third year of Huichang)

4. "Stele of Situ Liu Mian" (written in the third year of Dazhong, at the age of seventy-two, in Chinese regular script)

5. "The Monument of Wei Gongxian Temple" (written in the sixth year of Dazhong, at the age of seventy-five, in Chinese regular script)

6. "Stele of Gao Yuanyu, Minister of the Ministry of Civil Affairs" (written in the seventh year of Dazhong, at the age of seventy-six, in regular script)

7. "Fu Donglin Temple Stele" (written in the 11th year of Dazhong, at the age of 80, in Chinese regular script)

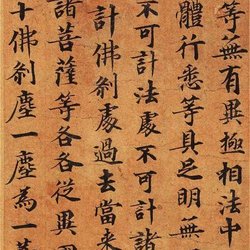

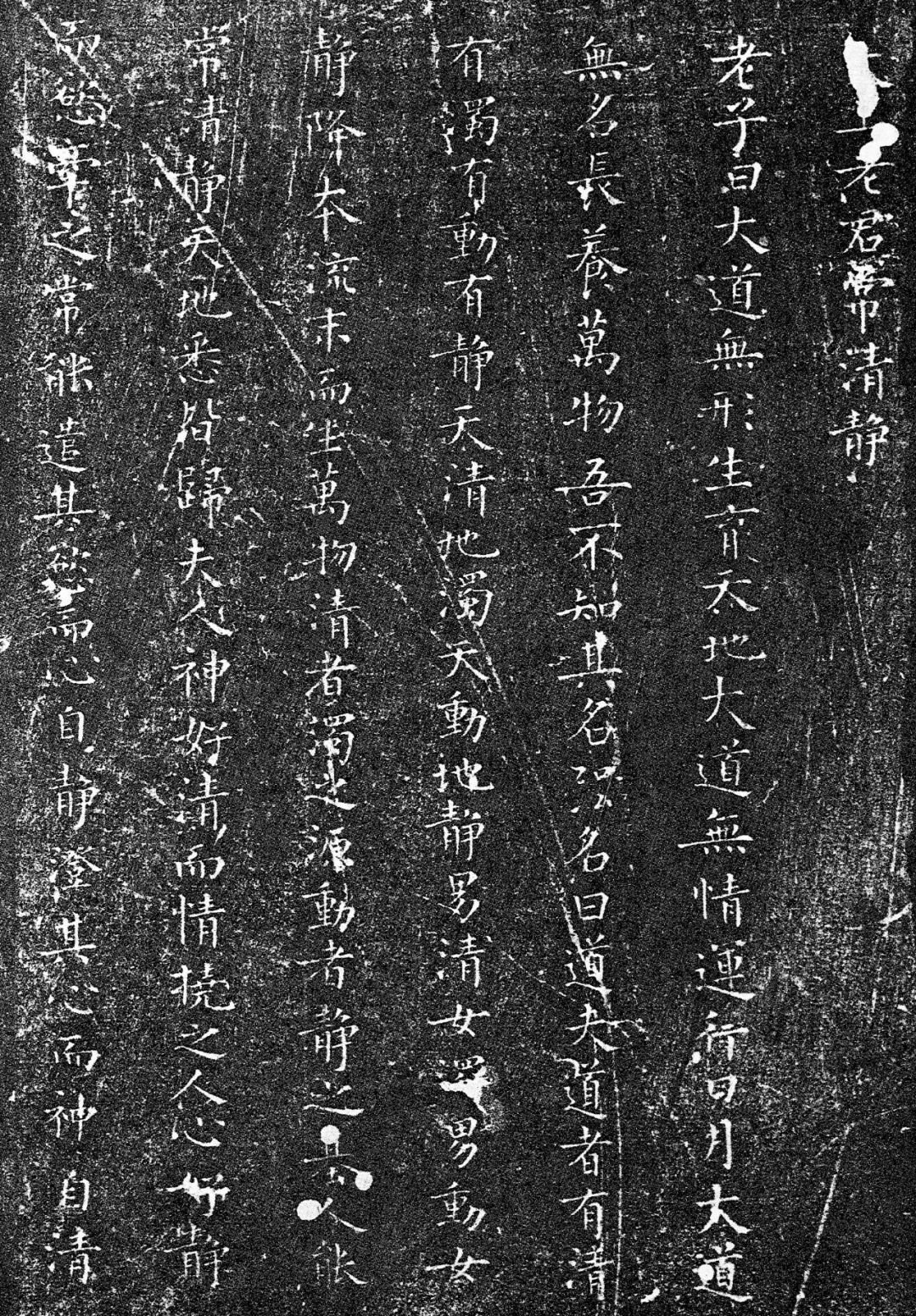

"Tai Shang Lao Jun's Sutra of Always Being Quiet"

The "Tai Shang Laojun Chang Qing Jing Jing" (also known as "The Chang Qing Jing Sutra" and "Qing Jing Jing") was written in the fifth year of its publication (840). This work has formed its own style, both in terms of brushwork and composition: The fonts are quite small, the strokes are very thin, and the strokes are heavy and rhythmic. Commenting on this book, Ye Yibao of the Qing Dynasty said:

Every word has its edge, and all calligraphers will appreciate it. Mi Haiyue (Fu) said that small characters should be as big as big characters and have the potential to find Zhang Zhang. This is what Mi Haiyue (Fu) said. Chengxuan's theory says: "It's as sharp as a cone and as sharp as a chisel. It can't be drawn out, so it has to be surrendered." The author can't do the right and wrong work.

The so-called "sharp as a cone, as sharp as a chisel" refers to the shape of the strokes, while "cannot draw, have to retreat" refers to the use of Zangfeng's brush. The structure of "Qingjing Jing" is different from the large tablet version written by Liu Gongquan, and there is absolutely no meaning of "big characters make it smaller, and small characters make it bigger". The size, length, width and width of the fonts are all natural. What is particularly noteworthy is the composition of this work, which is very widely spaced and sparse. Thin strokes, natural structures and sparse compositions complement each other, and the whole article is filled with an aura of indifference and tranquility.

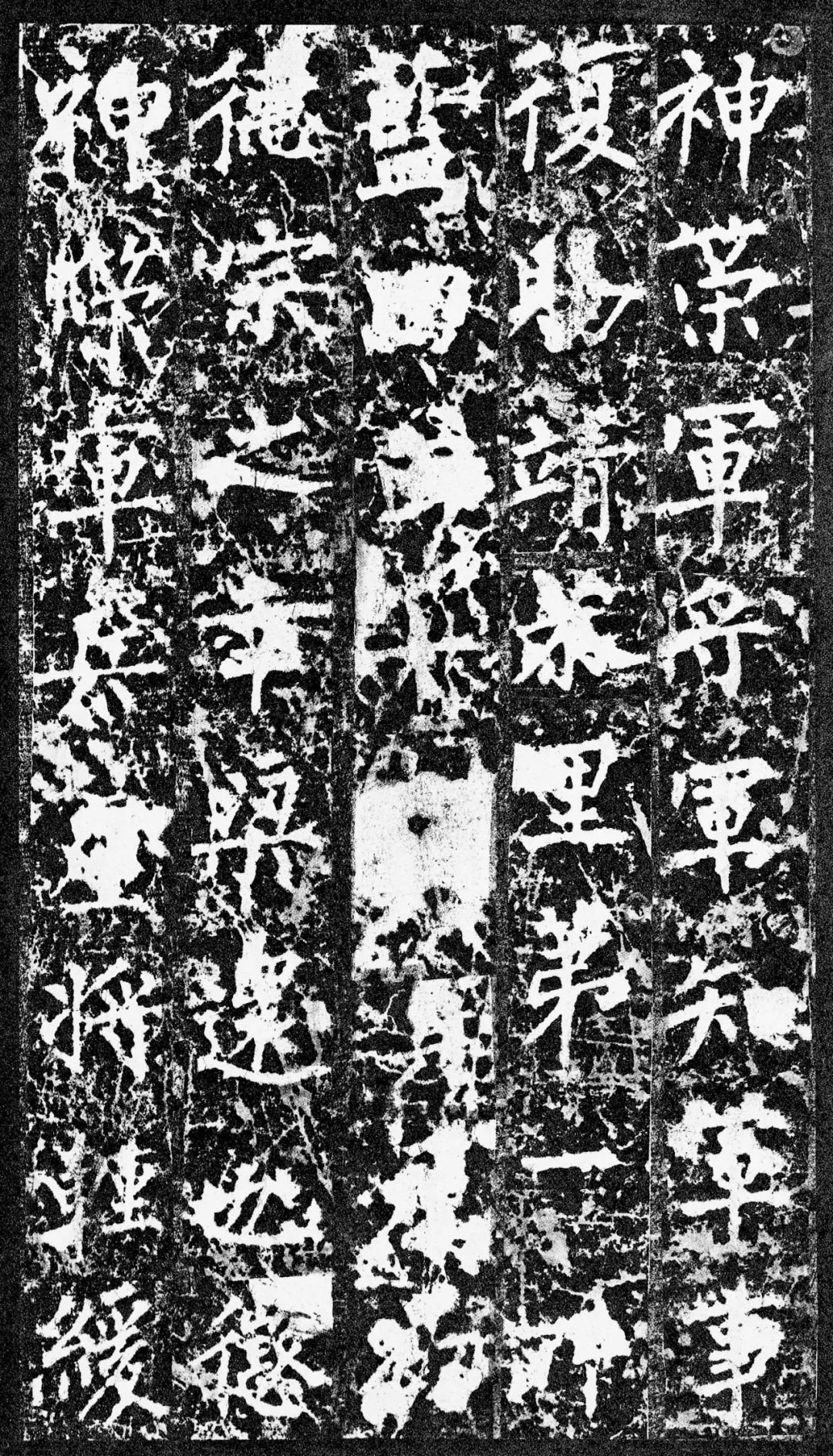

"The Military Monument of Divine Strategy"

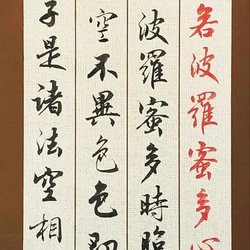

"Mysterious Tower Stele" and "Shence Military Stele" are representative works of Liu Gongquan's calligraphy. Since the "Shence Army Stele" was erected within the confines of the palace, its transmission was limited, and very few rubbings were circulated. Therefore, those who later talked about Liu style mainly referred to the willow style appearance represented by the "Mysterious Tower Stele".

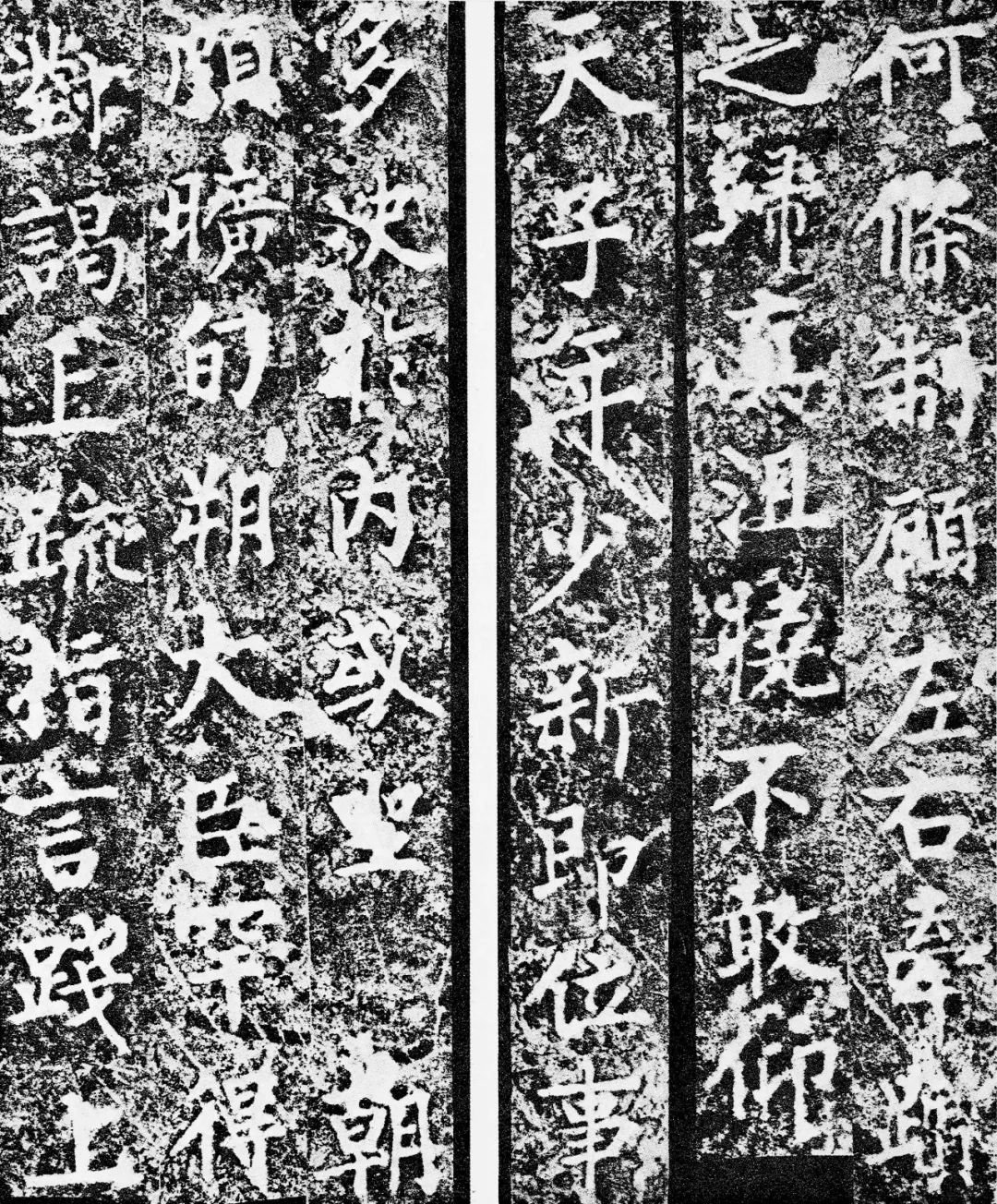

"Mysterious Tower Stele"

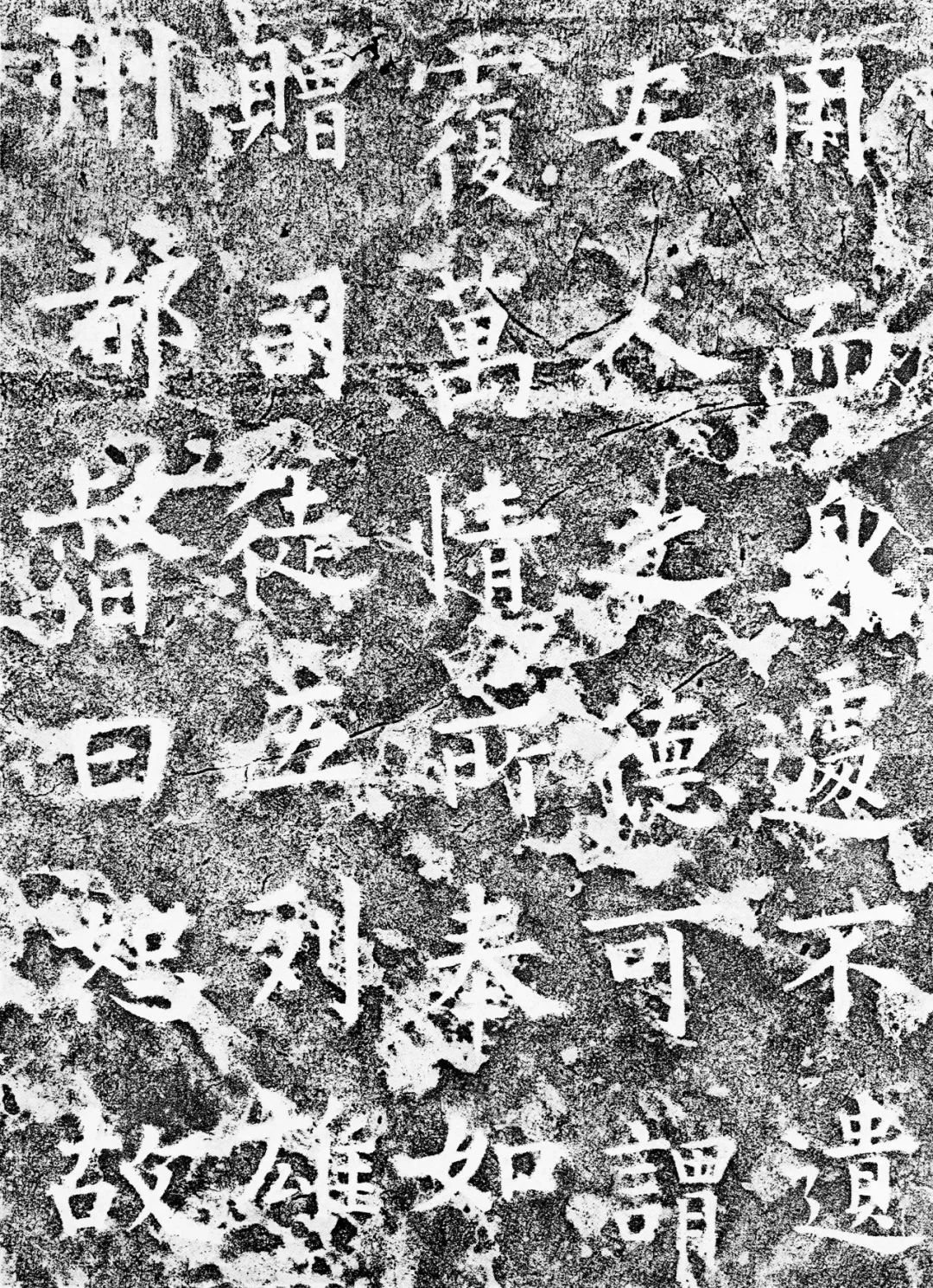

"Mysterious Tower Stele" is a milestone in the evolution of Liu Gongquan's calligraphy. It marks that Liu style calligraphy has become completely mature. In "Mysterious Tower Stele", we can see neither Ouyang Xun's force of arms, nor Chu Suiliang's dignified and graceful posture, nor Yu Shinan's elegant and humble attitude, which are displayed in people's eyes. What is in front of him is a new body shape that is completely different from his predecessors - the willow body.

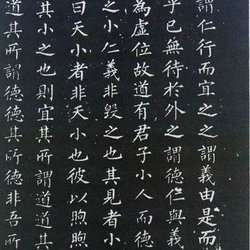

The Tang Dynasty was the heyday of the development of Chinese calligraphy. At that time, hundreds of flowers bloomed in the calligraphy garden, including seal script, official script, regular script, running script, and cursive script. Famous scholars emerged in large numbers and achieved unprecedented achievements. In terms of regular script, Yu Shinan in the early Tang Dynasty was soft on the outside and strong on the inside, as gentle as jade, like an elegant gentleman; Ouyang Xun was strong in writing, steep and rigorous, with the style of law enforcement and imperial disputes; Chu Suiliang was ethereal and elegant, and has become popular among the general public. The master of education: Yan Zhenqing is strong, strong, solemn and majestic, like a loyal and majestic man. Regardless of the subtlety and revelation of the brushwork, the slenderness and breadth of the structure, the gracefulness and strength of the style, the elegance and sublimity of the aesthetics, even looking back today, the creations of Yu, Ou, Chu and Yan are like towering into the sky. The peak is insurmountable. In this case, Liu Gongquan stood side by side with the peaks with the unique regular script he created. Although it is not unprecedented, it is indeed unprecedented. After Liu Gongquan, no new regular script style appeared again. He brought an end to the development of regular script style.

The Liu style style created by Liu Gongquan is obvious at a glance, and it is very different from his predecessors mainly in structure. The slender structure is just an appearance, while the inner tightness and outer looseness and strong sense of dynamics are its fundamental characteristics. Let’s talk about tightness on the inside and looseness on the outside first. The palace in the willow body is compact and relaxed on all sides. The strokes are gathered inward and radiate outward, giving the impression of a fortress.

1. Exaggerate the proportions of limbs and body in characters. If the long strokes extending to both sides of the character are considered limbs, then the strokes on both sides of the center of the character can be said to be the body. For example, the ratio between the upper part of the character "Ju" and the length and width is about 2:1 in face and body, so it looks broad and majestic; it is generally 2.5:1, but Liu Gongquan boldly wrote it as 3:1.

"Yin", "Zhe", "Zhi", and "日" are extremely thin; the two vertical strokes of the character "Gan" are extremely narrow, only three to one, or even less than three to one, the width of the character; although "家" does not have this This kind of long vertical painting is symmetrical on both sides, but the space occupied by the curvature of the vertical hook is also proportional to the width of the characters. Wang Xizhi and Ouyang Xun were slightly less than three to one, Yan Zhenqing was slightly more than three to one, and Liu Gongquan was four to one. This situation was extremely rare before Liu Gongquan. Although "Ji", "Jun", "Sheng", etc. do not have such an obvious "trunk", the "鹹" part of "Ji", the "Yin" part of "Jun", and the short horizontal part of "生" are extremely short. The exaggerated and even unafraid proportions are Liu Gongquan’s ingenuity.

2. The stroke shapes and gestures converge inward and radiate outward. The so-called strokes refer to the direction of stroke movement and the feeling brought by the shape of the strokes. In order to gather inward, the willow body with symmetrical vertical paintings on both sides will be retracted in many directions. For example, the character "国" is wider at the top and narrower at the bottom. The ends of the vertical paintings of "Ji", "Zhi" and "Zhi" are curved inward; those with short vertical paintings on both sides The inclination is extremely large. What is even more unique is that if the short vertical paintings that are symmetrical on both sides are placed at the top of the character, and if the vertical paintings are extended, they can intersect in the character, such as "Chong", "Si", "Mo", and "东" The "sun" part of "" and the "tian part" of "stele" and "god" actually intersect with the vertical paintings after they are extended. The vertical paintings on both sides are not only slanted, but also have straight lines. The ends of the vertical paintings on the right side are generally curved inward. Such as the "cause" part of "En", the "日" part of "Yang", "Bai", "Ji", "Zhi" and other similar shapes all use this technique. As mentioned above, Liu Gongquan exaggerated the proportions of his limbs and body, resulting in a tight posture, but we saw that Chu Suiliang sometimes also used this exaggerated proportion, such as "true" and "qi", but why do we feel delicate? It's graceful and graceful, but it doesn't feel tight. This is why Chu Suiliang's vertical paintings are curved, and they are curved inward and then outward, while Liu Gongquan's vertical paintings are concentrated toward the center, and in the end they have to increase the inward curvature.

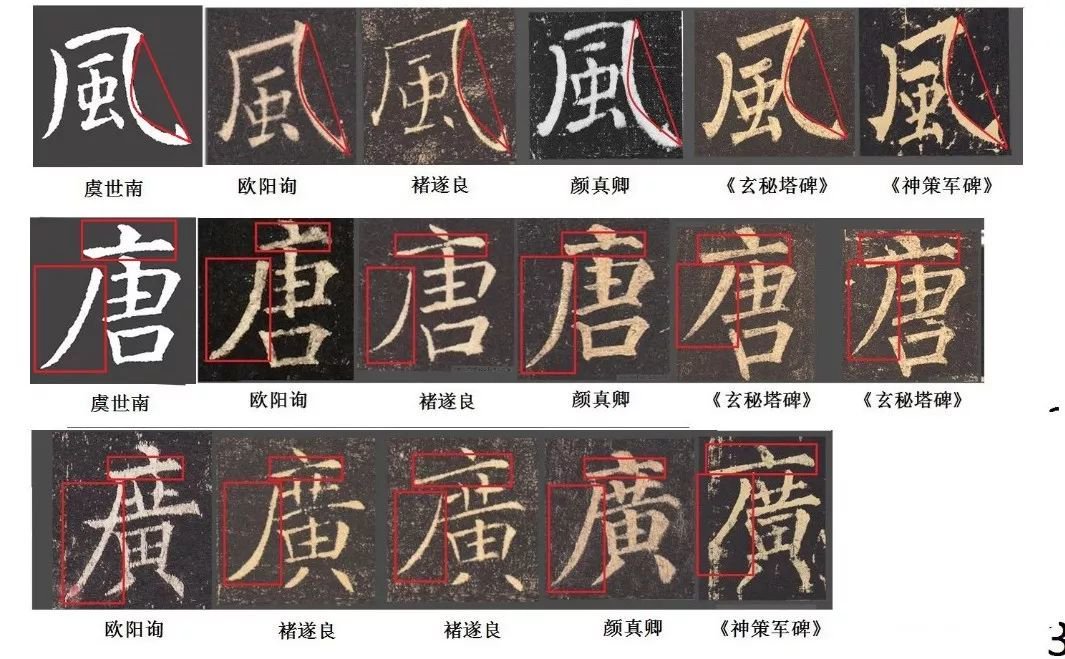

In order to highlight the internal tension, Liu Gongquan did everything possible. The horizontal and oblique hooks of "Wind" have gentle curves in Ou, Chu and Yan, while Liu Gongquan's curves are extremely large, as tense as a stretched bow. Characters starting with "Guang", such as "Tang", "Guang", "Du", "Chen", "An", etc. are usually written close to the left side of the horizontal stroke, but Liu Gongquan inserted the strokes into the horizontal stroke. .

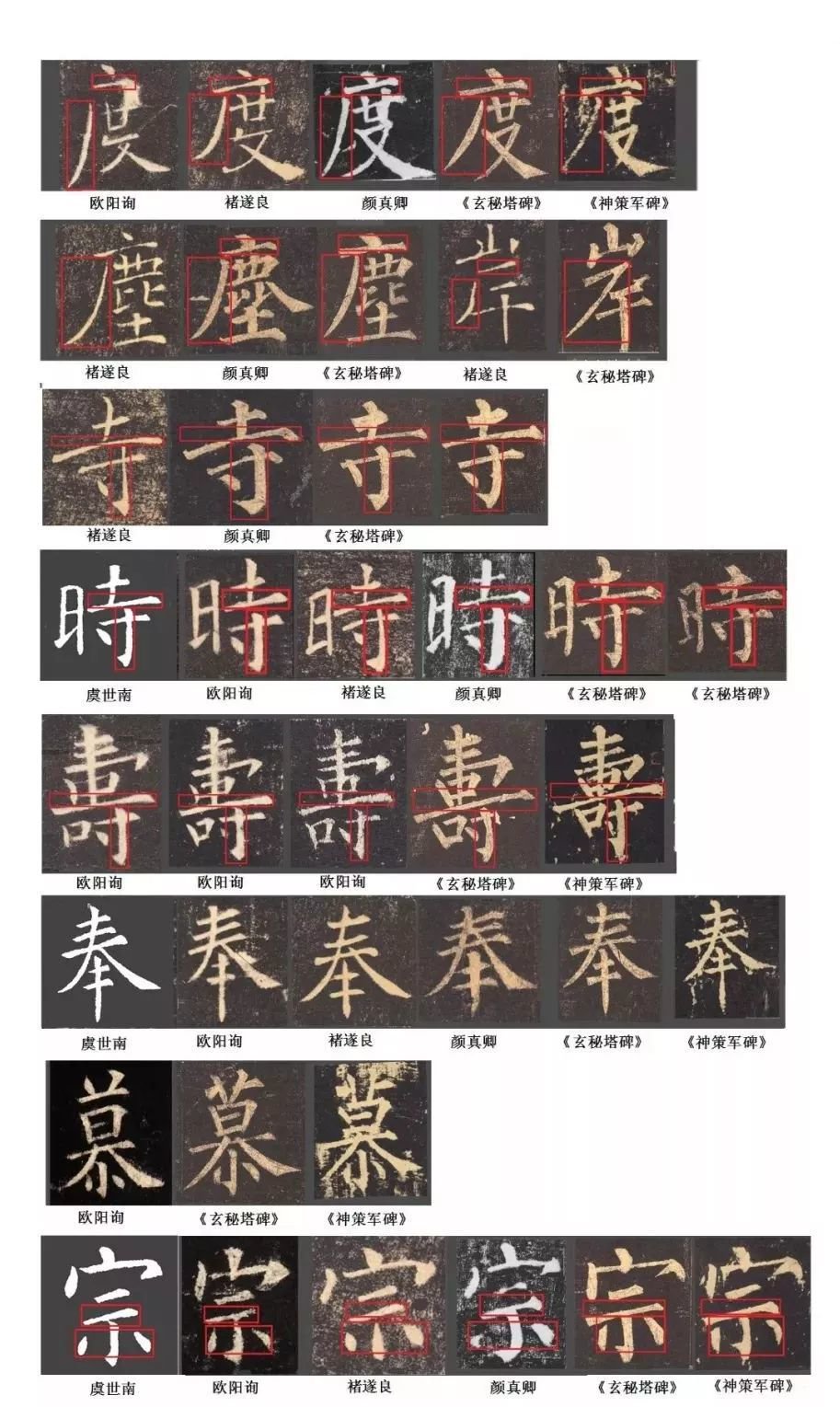

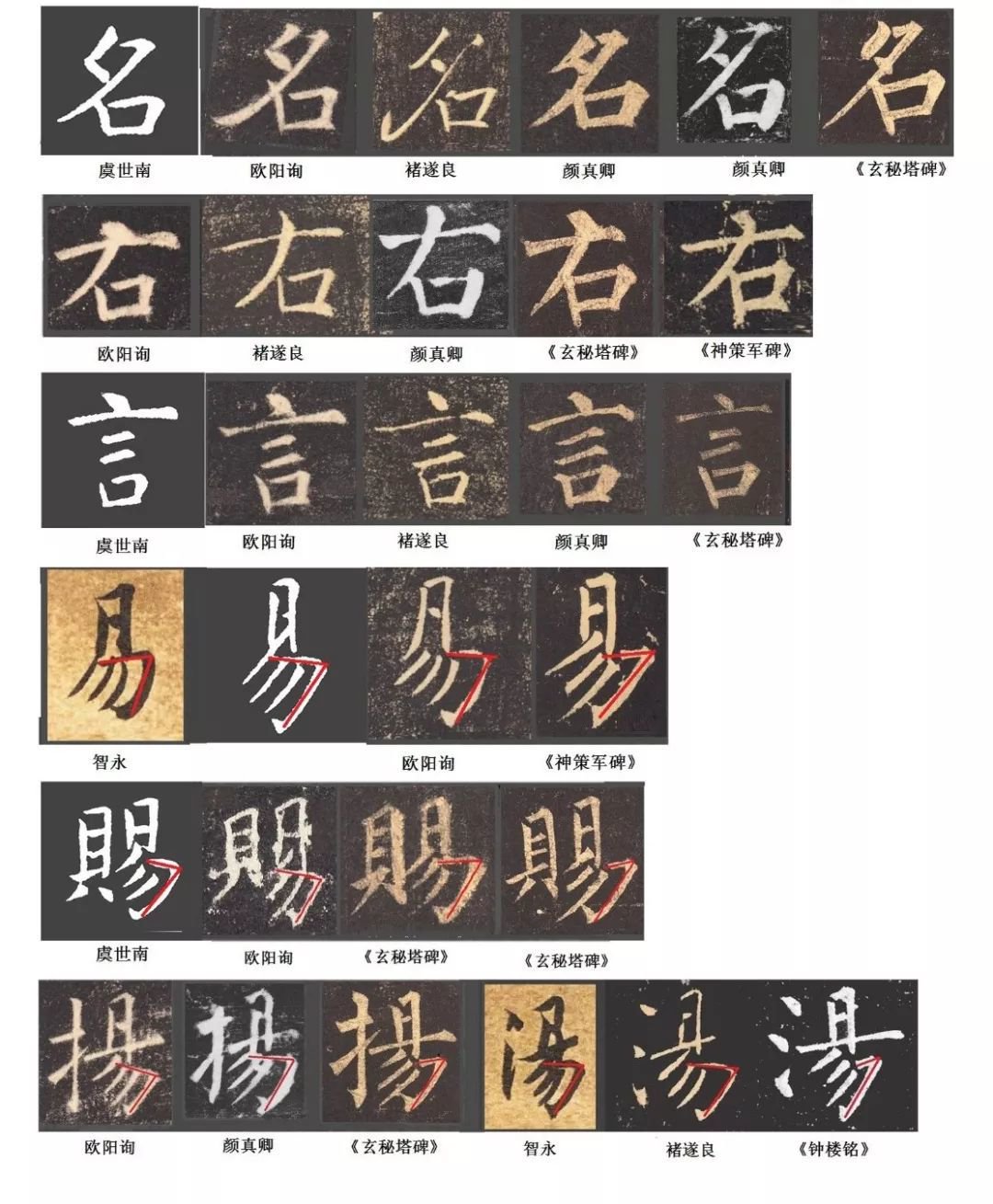

In the "Cun" part of "Temple", "Shi" and "Shou", Ou, Chu and Yan mostly lean to the right, while Liu Gongquan tries his best to squeeze towards the center, and some even lean to the left. Wang Xizhi, Ouyang Xun, Chu Suiliang, and Yan Zhenqing all started their strokes with "Feng" and "Mu" at a certain distance from the center line of the characters, while Liu Gongquan tried his best to move closer to the center line. The two points of the "Shi" part of the characters "Zong" and "Chong", Yu, Ou, Chu, and Yan are all wider than the upper horizontal, but Liu Gongquan hides the points under the horizontal.

The feeling of outward radiation from the willow body is mainly manifested in the following aspects:

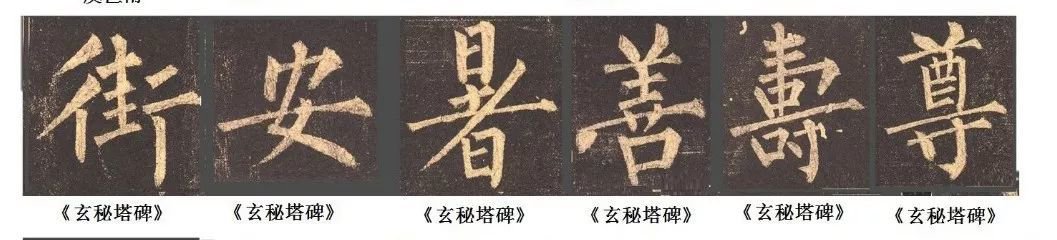

(1) Comparison. Because the inside is tight, the strokes that extend outward have a radiating feel even if they are not long. For example, the long strokes of words such as "Jie", "An", "Shu", "Shan", "Shou" and "Zun" are very prominent.

(2) People who are tight on the inside tend to be reserved, but Liu Gongquan, in order to stretch and highlight the feeling of radiating outward, does not hesitate to violate the conventions in writing some characters, such as "name", "right", "pin", "shan", "tang" and "yan" "The "mouth" part is flat or square, but the left side is vertically inserted downward. The bottom of the "kou" part of "Chang" is longer than the left and right sides. The characters of "Yi", "Ci", "Yang", "Tang", "Ti", etc., and the horizontal hook of the "Wu" part are all horizontal or horizontal to the right. The lower part hangs down, the vertical painting is slanted and curved, and the angle formed by the horizontal and vertical is relatively large. However, the horizontal painting written by Liu Gongquan is lower on the left and higher on the right. The vertical painting not only has a large inclination, but also has no curvature. The angle formed by the horizontal and vertical It's very small, and it feels like it's shooting to the upper right. These are Liu Gongquan’s unique creations.

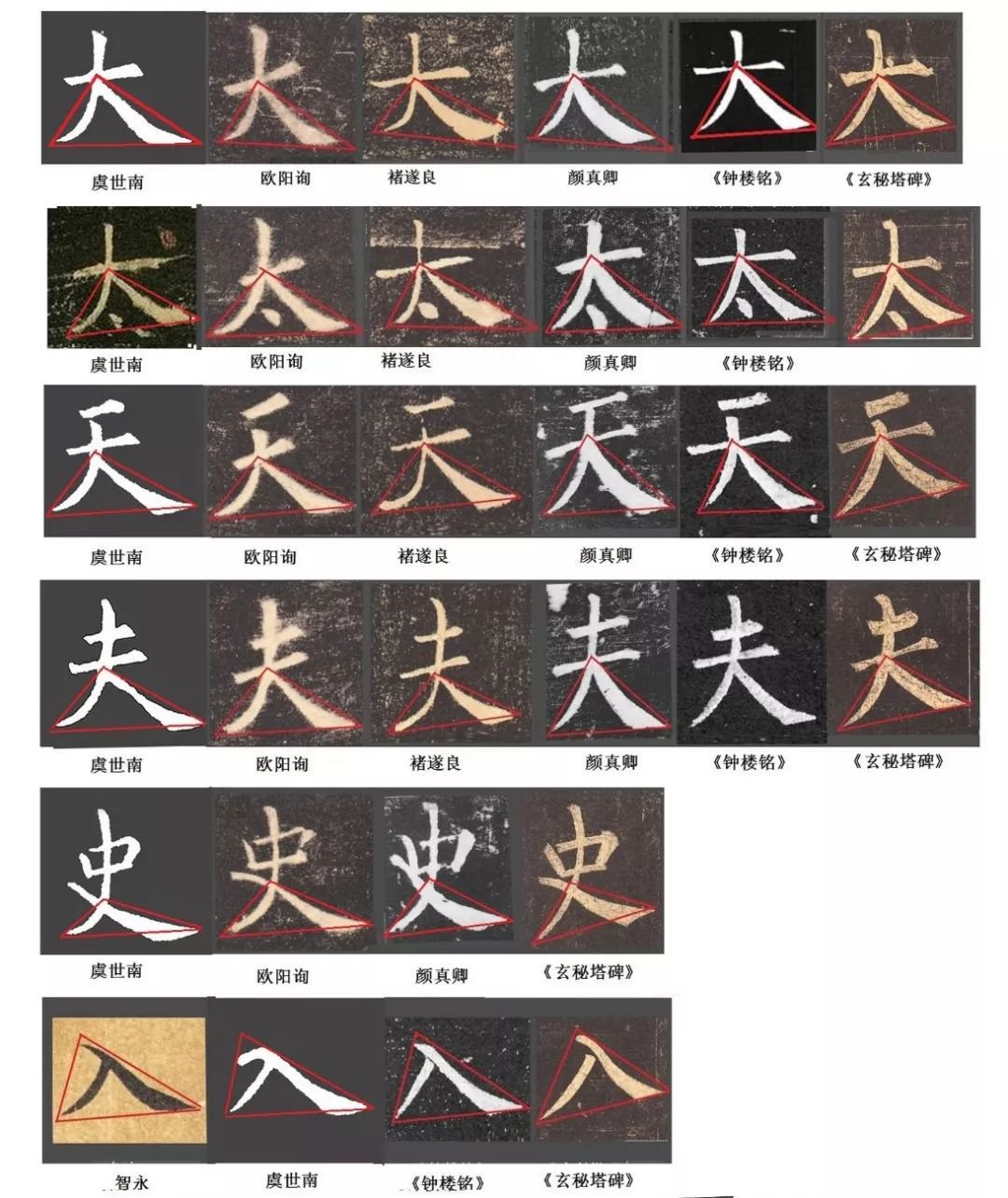

Another outstanding feature of the willow body is that it is extremely dynamic. In particular, the handling of the painting can be said to be unique. For example, in the words "Da", "Tai", "Tian", "Fu", "Ru" and "Shi", the terminal ends of Ou, Yu, Chu, Yan and other styles often fall on the same horizontal line, which is symmetrical and balanced, as if standing upright. The person has a calm attitude. The willow body is mostly lowered and lowered. Although it is thin, it is very strong and strong. It is thick and strong, but it is quite relaxed. It is still and moving, like a person moving forward, showing a graceful and elegant posture in its strictness. Ouyang Xun and Chu Suiliang also sometimes drew low and high, but the strokes were stretched and formed a scalene triangle. However, the strokes written by Liu Gongquan were not long, and the strokes formed an isosceles triangle with an upturned right corner. This can be It is said to be an unprecedented unique creation of Jiajia, which has become a unique symbol of Liu Ti.

Liu Gongquan did not have any new inventions in the brushwork itself. If you intercept certain strokes in Liu style and analyze his brushwork, you can almost always find the origin in the calligraphy of his predecessors. The biggest feature of Liu Gongquan's brushwork is that he can skillfully control various brushwork techniques and use them as he wishes. In contrast to the strict structure, Liu Ti's brushwork is very flexible. He does not use square, hard, thin and sharp strokes to reveal his muscles and bones. Instead, he starts the brush in many squares and ends in a round shape. His long paintings are thin and short paintings are fat. The vertical strokes are mostly straight and strong, and the horizontal strokes are round and vigorous, so they appear to be weighted and varied, showing strong bones and strong flesh and blood. Because the brushwork is flexible and changeable, the forms of willow-style pointillism are also rich and diverse. Even the same strokes have different shapes in different characters and in different parts. It can be said that they follow the body's shape and are not rigid. The style is very beautiful with decorative changes.

The very different appearance of Liu Ti from its predecessors is also reflected in the sharpness of its strokes. In conjunction with the tight central palace, relaxed surroundings, and radiating structure, the strokes on the willow body are very crisp and smooth, moving forward in an indomitable manner, and the strokes are still full of energy. Mr. Lu of the Tang Dynasty described the ferocity and speed of his writing style as "a frightened giant ducks away from a flying bird, a hungry eagle takes flight", while Zhu Changwen of the Song Dynasty thought it was still "not enough to describe its eagerness." What is particularly worth mentioning is that Liu Ti's eager strokes are not achieved by hard brush strokes like those of later generations of Liu Ti practitioners. Liu Gongquan used a soft brush with a long edge. Liu Gongquan's "Xie Renhui's Notes" in Volume 14 of "Neng Gai Zhai Man Lu" written by Wu Zeng of the Song Dynasty says:

I send you a pen in recent years, which expresses deep feelings from afar. Although the thin tube is very good, the strike point is too short and suffers from the strength. What you want is fine and soft, the beard must be long and the beard must be thin. The management is not big, but the details must be neat. Deputy Qi Zebo has Feng (which means "Ping"). If the control is small, the movement will be effortless, if the fineness is fine, the stippling will be flawless, and if the front is long, the flow will be free. A few years ago, I got a calligraphy master from Shuzhou Qing, and he gave me command and instruction. He was quite talented. Later, there was an elder named Guan Xiaofeng, and if he could benefit from it once or twice, it would be a great success.

After "Mysterious Tower Stele", Liu Gongquan created a large number of calligraphy works. Although most of the works have been lost, if you compare the five remaining works, you will find another example of Liu Gongquan's later calligraphy creations. Important features, that each piece has its own unique charm:

"The Military Monument of Shence" shows the feeling of respect;

"Stele of Situ Liu Mian"

"Situ Liu Mian's Monument" shows a strong state;

"Stele of Gao Yuanyu, Minister of Official Affairs"

The "Stele of Gao Yuanyu, Minister of the Ministry of Official Affairs" has a refined appearance;

"The Monument of Wei Gongxian Temple"

"Wei Gongxian Temple Stele" has a solemn atmosphere;

"Fu Donglin Temple Monument"

"Fu Donglin Temple Stele" is full of transcendental interest.

The influence of willow calligraphy on later generations is long-lasting, extensive and subtle. The so-called long-term refers to the fact that there is no shortage of people who have learned Liu style calligraphy since the Tang Dynasty. Until modern times, many calligraphy students take Liu style as a model for their practice. The so-called widespread means that Liu style calligraphy has many students among the people and foreigners. The Jin people of the Jurchen tribe once carved Liu characters into the "Stele of Puzhao Temple in Yizhou" (built in October of the fourth year of the Emperor's reign). The Liu style calligraphy on the "Mourning Book of Empress Daozong Xuanyi" of the Liao Dynasty shows the Liao people's love for Liu. of respect.

The so-called obscurity refers to the fact that Liu style calligraphy has never formed a calligraphy school comparable to the calligraphy schools of Wang Xizhi, Ouyang Xun, and Yan Zhenqing in later generations. In the history of calligraphy, there are many famous calligraphers from the schools of Wang Xue, Xue Ou, Xue Chu, and Xue Yan, but few have entered the halls of Liu Ti and spread their incense.

It is a prominent phenomenon in the history of calligraphy that one begins to learn something but ends up denouncing it and abandoning it:

Empress Li of the Southern Tang Dynasty learned nine out of ten Liu styles, but Li criticized Liu Shu for "gaining the bones of the right army but losing the rawness."

In the Song Dynasty, Mi Fu "began to learn Yan at the age of seven or eight. The characters were as large as a single page, and he could not write them down in simplified form. When he saw willow trees, he admired the knot tightly, so he studied Liu's Diamond Sutra. Over time, he learned that he came from Europe, so he learned from Europe." However, after he established his own family, he severely criticized Liu Shu: "Liu Gongquan's master Ou Bu is not as good as Yuan Yuan, and he is the ancestor of ugly and evil books. Since the Liu Dynasty, there have been vulgar books."

Kang Youwei studied calligraphy and also "combined" "Guifeng" (that is, Pei Xiu's "Guifeng Zen Master Stele"), "Yu Gonggong" (Ouyang Xun's book), "Xuanmi Pagoda", and "Yanjia Temple" (Yan Zhenqing's book) to compile In other words, it means less understanding of the structure." However, when he published his disparaging remarks about the Tang Dynasty, Liu Gongquan was also among those criticized: "As for the existence of the Tang Dynasty, although calligraphy was established, the scholar-bureaucrats especially talked about it. However, one or two of the legacy can no longer be changed. Special lectures The structure is almost like an arithmetic; the crane is cut off and the duck is continued, which is too neat. Although the writing techniques of Ou, Yu, Chu, and Xue are not completely dead, they are pure and simple, and the ancient meaning is already vivid, while Yan and Liu are playing repeatedly, and they are all gone. That’s it.”

From the Song Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty, only Dong Qichang, who advocated the Zen style of calligraphy in his later years, was the only one who studied Liu's poetry without criticizing it. Dong Qichang said: "Liu Chengxuan wrote and tried his best to change the military law of the right. He did not want to be similar to the "Han Tie" (i.e. "Lanting Preface"). The so-called magic turned into decay, so he left his ears. Ordinary people study books and take them with posture. Mei, few can explain this. Yu Yu, Chu, Yan, and Ou were all like eleven. I studied Liu Gongquan by myself, and then I realized the ancient and dull ways of using brushes. From now on, I can't abandon Liu's method and go to the right army." But What Dong Qichang said was not understood by future generations. Instead, it was considered to be deceptive, and he wanted to "cling to" Liu and pass it on to the world.