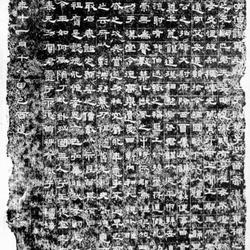

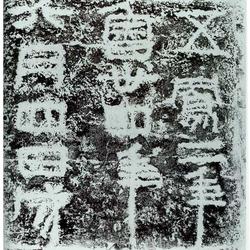

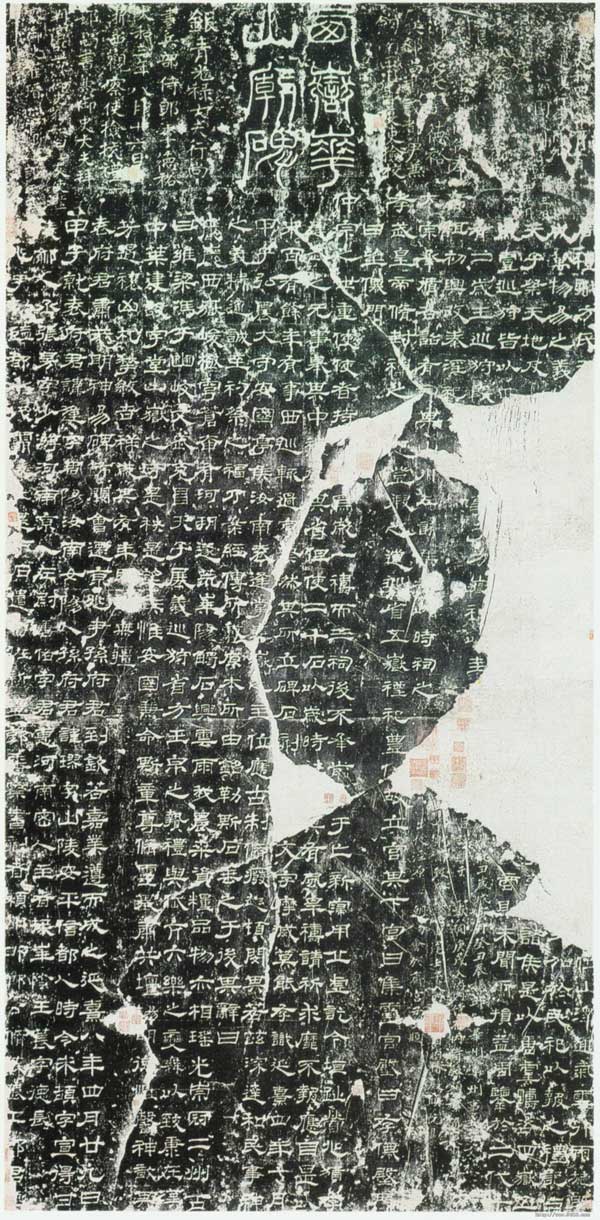

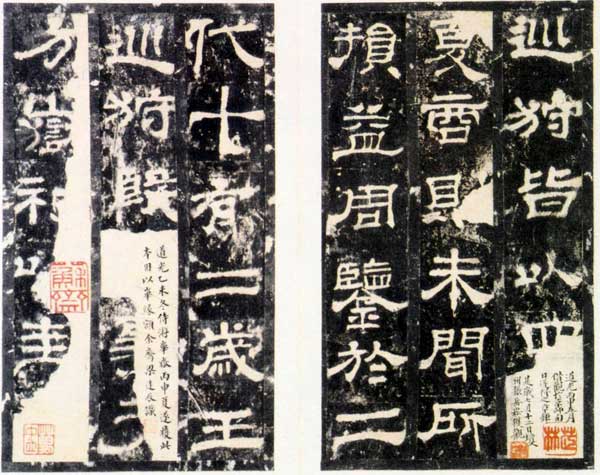

Eastern Han Dynasty official script inscription. The seal on the forehead is inscribed "Xiyue Huashan Temple Stele". It was established in the Xiyue Temple in Huayin County, Shaanxi Province in the eighth year of Yanxi's reign (165). One is said to have been written in the fourth year of Yanxi's reign. "Jin Shi Cui Bian" records: the stele is seven feet seven inches high and three feet six inches wide, with a total of twenty-two lines and a full line of thirty-seven characters. It was destroyed by an earthquake in the 34th year of Jiajing reign of Ming Dynasty (1555). From now on, those who survive in the temple will be re-engraved.

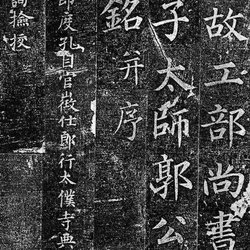

The inscription on this stele records the emperor's practice of Zen and worship of heaven and earth. The calligraphy of this stele has undergone many changes during the period of regulation and strictness, and is highly valued by those who study Han Li. Because there are four words "Guo Xiang Cha Shu" at the end of the stele, it has aroused discussion among scholars of all ages. Some think it is "Guo Xiang Cha"'s book, while others think "Guo Xiang" Cha Shu came to other people's books. There is also Tang Xuhao's "Records of Ancient Monuments". It means that it was written by Cai Yong, and the person who "chashu" (meaning to check and proofread) is Guo Xiang. But he did not provide sufficient evidence to explain why it was written by Cai Yong. Once this was said, it had a huge impact. For example, Song Hongshi's "Li Shi", Gu Yanwu of the Qing Dynasty's "Li Bian", Gu Nanyuan's "Li Bian" and Weng Fanggang's "Li Bian", etc., are all based on Xu's theory. Ming Guo Zongchang's "History of Epigraphy" and Zhao Kan's "Graphite Engraving Hua" began to doubt this theory, and the person who believed that the real calligraphy was Guo Xiangcha. In the front catalog of "Graphite Engraved Hua", under "Huashan Stele", it is titled "Guo Xiangcha Shu", while "History of Epigraphy" directly calls "Huashan Stele" "Xiangcha Stele". Modern scholars have basically confirmed that Guo and Zhao's theory is correct, and Mr. Qi Gong's article has the most detailed argument (see "Qi Gong Series", Zhonghua Book Company, 1981 edition).

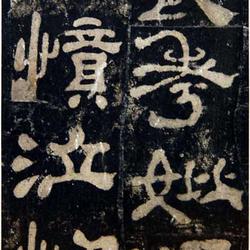

This stele, like the Ritual Vessel Stele, is hailed as a model among Han official scripts. It is elegant and upright, harmonious and dense, with neat words and line spacing, beautiful ripples, and the atmosphere of a temple. It is the main line of official script. Guo Zongchang of the Ming Dynasty said in his "History of Metal and Stone" that "the movement of the body and movement is the majesty of the Han Dynasty". Jin Nong, a famous official script writer in the Qing Dynasty, once praised "Huashan Shanshi is my teacher". Zhu Yizun of the Qing Dynasty commented on this stele and said: "There are three kinds of Han Li, one is square, one is smooth, and the other is strange and ancient. But Yanxi's "Huayue Stele" is a perfect combination, which is unprecedented, and has all three. Its length should be the first rank of Han Li." (Postscript to "Inscriptions on Epigraphy and Stone"). Liu Xizai also said: "The steles of the Han Dynasty are as sparse and scattered as those of Han Chi and Kong Zhou, and as strict as those of Heng Fang and Zhang Qian. They are all in the flourishing state of Li. Like the Huashan temple steles, they are majestic and dense, flowing and frustrated, and their meanings are inexhaustible." ("Yi Gui") Weng Fanggang said: "Zhu Zhucong's most recommended stele in the Han Dynasty. From Yu Pingxin's perspective, the Han Li's "Liu Utensil Stele" is the most popular. The upper part of this stele is in seal script, and the lower part is also in regular script. , so as to see the reason why the front and rear changes are so, this stele is easy to see in the origin of calligraphy. What makes it easy to see is not the original one." ("Emperor and Stone Records of the Two Han Dynasties")

This stele was valued in the Tang Dynasty, and there should be a rubbing of it, but it has not been handed down. There are four old rubbings of the original stone handed down from generation to generation.

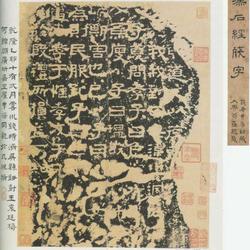

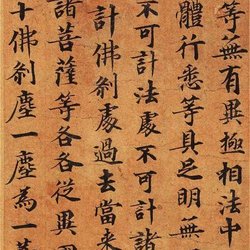

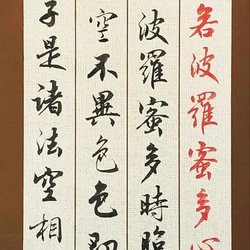

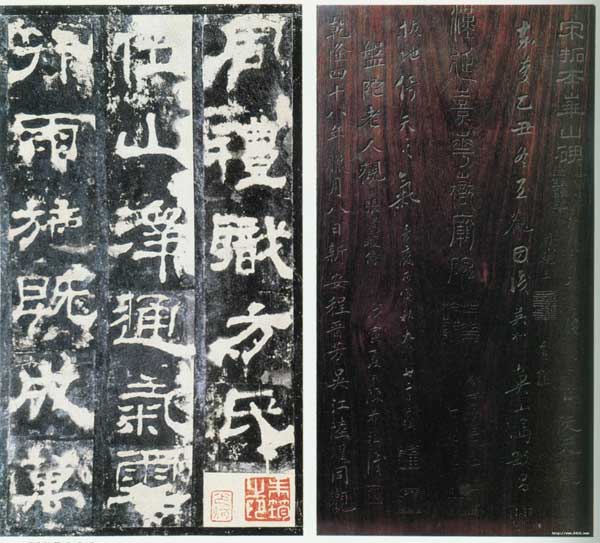

1. Changyuan version, also known as "Shangqiu version". Because in the Ming Dynasty, Wang Wensun's place in Changyuan (now part of Henan) was hidden, and after the Qing Dynasty, it was hidden in Shang Qiu and Song Nao's place, so it has these two names. Later, it was handed over to Chen Chongben, Yongli, and Duanfang. Later, Wu Rangzhi, Zhu Yizun, Song Nao, Chen Chongben, Weng Fanggang, Ruan Yuan, He Shaoji, Weng Tonghe, and others wrote postscripts. It was an early copy of the Song Dynasty and was later attributed to the Nakamura Fusaki family in Japan.

2. Huayin version, also known as "Guanzhong version". In the Ming Dynasty, it was stored in the Mozhuang Tower of Huayin Shang brothers Yunju and Yunzhao. It was later collected by Guo Zongchang and Wang Hong in the Qing Dynasty. Zhu Yizun and Duanfang passed it on to the collection. The post was followed by inscriptions and postscripts by Guo Zongchang, Wang Duo, Weng Fanggang and Qian Qianyi. Now in the Palace Museum,

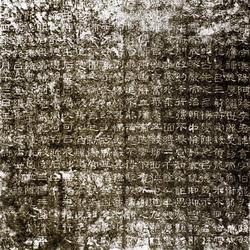

Three and four Ming editions. Original rubbing of the entire piece mounted on scroll. It was collected by Feng Daosheng in the Siming Dynasty and was stored in Wanjuan Tower in Fengfang, Ningbo. It also belonged to the Fan family in Tianyi Pavilion, Ningbo. In the Qing Dynasty, it belonged to Xieshan, Qian Daxin, Ruan Yuan, Duanfang and others, and finally to Hu Huichun in Hong Kong. In 1975, Hu Huichun donated it to the Cultural Relics Bureau of the Ministry of Culture for collection in the Palace Museum. The scroll is surrounded by inscriptions by Weng Fanggang, Chen Chongben, Ruan Yuan, He Shaoji and others, which have been intact for hundreds of years. It allows us to get a full view of the original stele, which he was unable to do.

4. The Shunde version, which is the version kept by Jinnong Jindong, has several seals from "Xiao Linglong Shan Guan" by brothers Ma Yuelu and Ma Yueguan, Jin Nong's friends, so it is called "Linglong Shan Guan". Unfortunately, there are only two pages and ninety-six words. In the late Qing Dynasty, Li Wentian (1834-1895), the superintendent of schools in Shunde, Guangdong, purchased it for three hundred gold and silver, and it became a treasure in his "Taihua Building". Zeng Yan and Zhao Zhiqian filled in two missing pages from the hooked edition, and Hu Chuan re-hooked two pages from the Changyuan edition. In the last years of Guangxu, Duan Fang, the governor of Liangjiang, tried his best to buy this post from Li's son, but failed. After the Second World War, this rubbing belonged to Mr. Lee Wing-sen's "Beishan Hall" in Hong Kong. Lee later donated this rubbing to celebrate the completion of the new building of the Cultural Institute of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the establishment of the Art Museum. It is now in the collection of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The above four volumes all have photocopied editions in circulation, and there is also a Song rubbing from the Zhenhan Pavilion published in Hong Kong's "Shupu", which is actually a forgery.